Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

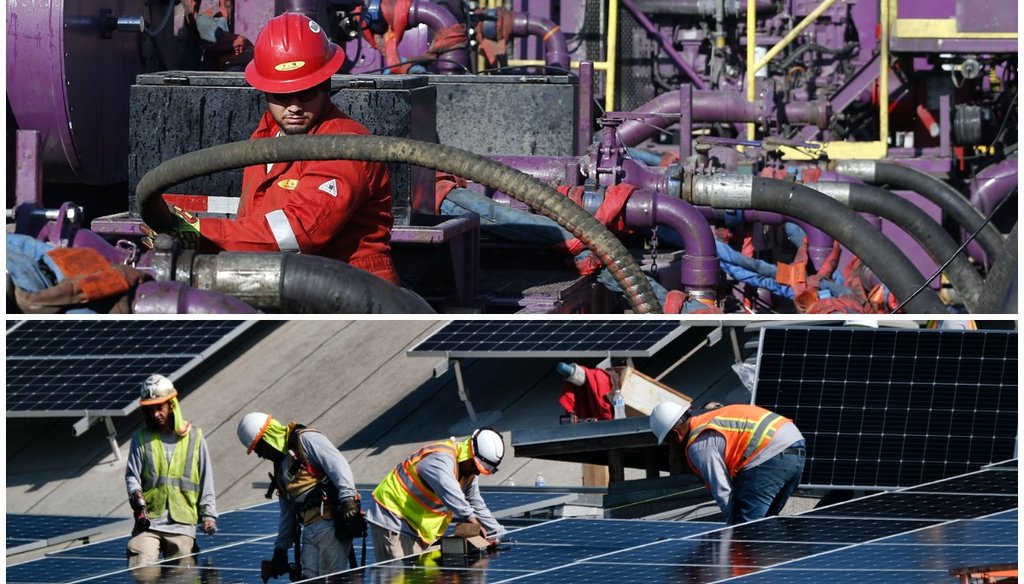

President Joe Biden aims to promote renewable energy, but many in the fossil fuel sector fear that will come at their expense. (AP Photo/Brennan Linsley/Richard Vogel)

If Your Time is short

-

The Biden administration argues that tackling climate change can create enough high-paying jobs to ease the transition away from fossil fuels.

-

The nation’s track record on helping workers through past transitions is poor.

-

Studies comparing renewable energy and fossil fuel jobs reach different conclusions depending on which types of jobs they include. Fossil fuel industries currently have a higher concentration of high-wage jobs, but the growth outlook is better for renewables.

President Joe Biden believes Washington can deliver on two big promises at the same time: tackling climate change and creating jobs. And his policy dreams depend on his ability to effectively sell that idea.

Biden is bullish on the prospect that clean energy can be the same kind of economic engine that the fossil fuel industry once was, generating a broad range of secure, high-wage jobs.

"I see an opportunity to create millions of good-paying, middle-class union jobs," Biden said as he opened a global Earth Day summit April 22. "I see laborers and line workers laying thousands of miles of transmission lines for a clean modern resilient grid. I see workers capping hundreds of thousands of abandoned oil and gas wells that need to be cleaned up, and abandoned coal mines that need to be reclaimed."

Republican Sen. John Barrasso of Wyoming, a major producer of coal, natural gas and oil, rejects such forecasts.

"Saying no to American energy production means less energy, less economic activity and less money in the pockets of American workers," Barrasso said in a Senate floor speech in January.

Sign up for PolitiFact texts

Sen. John Barrasso, R-Wyo., highlights statements that undermine fossil fuels during confirmation hearings for Rep. Debra Haaland, D-N.M., to be secretary of the interior. (AP)

Biden’s policy, Barrasso said, "sacrifices energy jobs to try to stop climate change."

To some extent, the two sides are talking past each other. Lawmakers from states that depend on fossil-fuel industry jobs tend to look at the transition to renewable energy as a threat to those jobs and the economies they support. The Biden administration prefers to focus on the new jobs that fossil-fuel workers and others could do in an economy transformed by clean energy.

Both views are valid. The sheer number of jobs that depend on the fossil-fuel industry poses a daunting challenge for any champion of renewables to argue that they can all be substantially replaced.

But it’s not a zero-sum game. Energy jobs of all kinds pay better than the average American job. The fossil-fuel industry has time to diversify into renewable sectors. And someone who doesn’t work in the energy field could find lucrative opportunities as the renewable sector expands.

As with other technological revolutions, new jobs will appear and others will fade. How individual workers, families and local economies will fare depends on the pace of change and how much Washington and employers are prepared to do to ease the transition.

The broadest look at energy jobs comes from a collaboration led by former Obama administration Energy Secretary Ernest Moniz at Energy Futures Initiative, a Washington-based policy group. Its April report on wages and benefits in the energy sector pulled together data on more than 8 million workers tied in some way to energy work.

The scope included coal miners in Wyoming and insulators in New England. It included truck drivers, nuclear engineers, accountants and energy wholesalers and traders.

Under this big umbrella, energy-efficiency workers outnumber all other groups by at least a factor of three. That’s because so many jobs fit this category. These are people who install and fix renewable-source heating and cooling units. They insulate homes, build double-pane windows and sell all the products needed for energy efficient buildings.

As of 2019, over a quarter of all energy workers were in energy efficiency, with a median wage of $24.44 an hour.

The national debate is focused more on jobs in producing energy, not saving it. The sum of those jobs tied to fossil fuels — oil, natural gas and coal — is about 2-1/2 larger than renewables — solar, wind, hydropower and storage (think batteries and smart grids).

Not all of these jobs are in the field. The numbers include accountants, energy traders and managers. But even teasing out the grittier work in construction or mining, that 2-to-1 ratio of fossil fuel to renewable energy jobs remains.

Oil pipeline workers bend a large section of pipe in Sumner, Texas. (AP)

So based on the situation right now, the people who work in fossil fuels have a point when they question the capacity of the renewable sector to provide enough replacement jobs.

Larry Barragan is a 57-year-old head operator in field operations at a Carson, Calif., fuel distribution center. From its 86 storage tanks, the facility pumps gasoline, diesel and jet fuel across the state to Arizona and Nevada. Barragan has seen policy-driven downturns before, but a more fundamental shift to renewable energy worries him.

"I was there in the 1990s when we saw refineries shut down," Barragan said. "I had to find a new part of the industry to work in. I thought, people will always need gas for their cars, I’ll get into the distribution side."

"When we hear about renewables," he said, "we don’t know what that really means for us."

In the medium term, the job trends favor renewables. Employment in wind and solar rose 22% between 2015 and 2019. Petroleum and natural gas employment grew at less than half that rate, 9%. Coal industry jobs nosedived 18%.

It isn’t just the number of jobs that matters, it’s the pay. Democrats promise jobs with good compensation. The question is: Good compared with what?

Pay in the energy industry varies from region to region, the specific sector, the kind of skills needed, whether there’s a union, and a few other factors. Barragan said the starting wage at his union shop is about $10 an hour more for someone doing exactly the same work at a non-union tank farm four miles away.

The top-line comparison from the Energy Futures Initiative report puts nuclear at the top of the wage scale, fossil fuels about in the middle, and wind and solar near the bottom.

The contrast between natural gas and wind power was stark. The natural gas median wage was $30.33 an hour. For wind, it was $25.95 an hour. That’s a difference of about $9,000 a year.

But another report by a different set of collaborators reached a different result.

"Jobs in coal, natural gas and petroleum fuels paid $24.37 an hour, while solar and wind jobs combined for a $24.85 median hourly wage," was a top-line finding in the Clean Jobs, Better Jobs report from Environmental Entrepreneurs, the American Council on Renewable Energy and the Clean Energy Leadership Institute.

Wind turbines atop Saddleback Wind Mountain in Carthage, Maine. (AP)

How could renewables come out ahead?

Bob Keefe, the head of Environmental Entrepreneurs, said it had to do with comparing similar kinds of work, not the type of energy a person helped produce.

"Look at a roustabout on an oil field and then look at a solar panel installer," Keefe said. "Neither one needs a special degree, and the solar panel installer makes more."

According to U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics data, the solar panel installer’s yearly pay is about $6,000 higher.

"When you include the generation side — like the wages of engineers at power plants — the comparisons aren’t as good," Keefe said. "But do you compare a solar installer to an engineer, or to a guy out in the field?"

Both this report and the one from Energy Futures relied on BW Research, an independent consulting group, to run the numbers. BW Research’s Philip Jordan told us that for jobs with about the same level of training, wages were about the same across the types of energy.

But it was also true, Jordan said, that the fossil fuel sector overall had a higher concentration of higher-paid jobs.

There was one point on which both reports were in full agreement.

Work in the energy sector, whether fossil or renewable, paid well above the national median — about a third higher for the same kind of work.

There’s a term in the climate change community that gets under Barragan’s skin: "just transition." It means ensuring that workers’ livelihoods and rights are protected as the economy shifts toward renewables.

The fuel distribution operator hears it from other union workers. But he’s not convinced that it’s a realistic expectation.

"They keep talking about a just transition, a just transition," Barragan said. "What I ask is — are they going to put us to work making solar panels? Are you going to guarantee me the $40 to $50 an hour people get now? Or will they pay me a few dollars above minimum?"

Mijin Cha, a climate justice researcher and assistant professor in the urban and environmental urban department at Occidental College, backs the idea of a just transition, but also echoes Barragan’s concern. She partnered with a group called Labor Network for Sustainability on a project to hear from workers who had seen their factory jobs disappear. And she says American workers have good reason to doubt that the government will have their backs.

"The U.S. largely has been unable to transition workers away from declining industries," Cha said. "None of us are saying we shouldn't be having an energy transition. But historically, it’s workers who bear the burden of these big changes, and they shouldn’t be doing so."

Cha pushes back against the idea that renewable energy jobs need to replace fossil fuel jobs one-for-one. According to one analysis, a quarter of the counties with strong potential for wind and solar are also employment hubs for the fossil fuel industry. But that still leaves a lot of territory where there may not be renewable energy jobs where every fossil fuel job is lost.

"We need to be talking about occupations, not industries," said Joseph Kane, a labor market researcher at the Brookings Institution, a Washington policy center. "The key is to help people get skills that can easily transfer into different industries. And where they can build experience so their wages go up."

To help the transition, Biden’s infrastructure proposal has $2 billion to train welders, sheet metal workers, and other skilled labor in clean energy jobs. There’s also $550 million to cap stranded oil and natural gas wells and abandoned mines.

But the ease of the transition will depend on how well and how willingly the legacy energy sector adapts.

The global consulting firm Deloitte wrote last fall — before Biden took office — that the forces of change are at work on the oil and gas industry, thanks to shifts in demand, new technology and an aging workforce.

"The oil and gas industry is in a ‘great compression’ where companies’ room to maneuver is restricted," Deloitte analysts wrote.

Two of their key recommendations were to move their industries into green energy and train their workers to move beyond doing a single, specialized job.

The United Mine Workers union is also advancing a broader approach. It unveiled a roadmap for helping miners and mining communities find a new economic balance. Their plan requires hefty spending on activities such as capturing atmospheric carbon, paying miners to reclaim old mines, and rebuilding roads, bridges and schools. Those wouldn’t be energy jobs, but they would be jobs.

For the miners, the need is pressing. Oil and natural gas workers have more time. By one estimate, demand for natural gas will remain high for at least a decade or two.

"Gas is not a climate savior, but it also is not going anywhere any time soon," a January analysis from the Center for Strategic and International Studies said.

Time is the overlooked factor in the debate over renewables versus fossil fuel jobs. Daniel Bresette, head of Environmental and Energy Study Institute, a bipartisan-oriented policy group, said the transition is likely to play out "over years and years."

"There will be change, and it will be more painful for some than others," Bresette said. "People worry that they will be left to some pitiless, merciless transition. But it doesn’t have to be that way."

Join PolitiFact LIVE on May 10-13 for a festival of fact-checking with Dr. Anthony Fauci! Register today >>

UPDATED, April 22, 10:13 a.m.: This story was updated to include comments from President Joe Biden’s speech at the Earth Day summit on April 22.

Our Sources

White House, Leaders Summit on Climate - Day 1, April 22, 2021

White House, Remarks by President Biden on the American Jobs Plan, March 31, 2021

The New York Times, Biden will commit the U.S. to cutting greenhouse gas emissions in half by 2030, April 21, 2021

United Mine Workers of America, Preserving Coal Country, April 19, 2021

Louisville Public Radio, Welcome to Appalach-America: Gina McCarthy, April 6, 2021

White House, Press Briefing by Press Secretary Jen Psaki and Secretary of Energy Jennifer Granholm, April 8, 2021

Environmental Entrepreneurs, Clean Jobs, Better Jobs, Oct. 22, 2020

Energy Futures Initiative, Wages, Benefits, and Change, April 6, 2021

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Occupational outlook handbook, accessed April 19, 2021

Center for Strategic and International Studies, How Will Natural Gas Fare in the Energy Transition?, Jan. 14, 2021

Labor Network for Sustainability, Workers and Communities in Transition, 2021

Environmental and Energy Study Institute, Jobs in Renewable Energy, Energy Efficiency, and Resilience, July 23, 2019

Ohio River Valley Institute, Repairing the Damage from Hazardous Abandoned Oil & Gas Wells, April 2021

Brookings Institution, Biden needs to create an infrastructure talent pipeline, not just more jobs, Jan. 29, 2021

Brookings Institution, How renewable energy jobs can uplift fossil fuel communities and remake climate politics, Feb. 23, 2021

Politico, Biden takes on Dems’ ‘Mission Impossible’: Revitalizing coal country, April `8, 2021

Interview, Crystal Herrera, electrician, April 17, 2021

Interview, Larry Barragan, chairman, Los Angeles/Long Beach Labor Coalition, April 18, 2021

Interview, Joseph Kane, associate fellow, Brookings Institution, April 19, 2021

Interview, Mijin Cha, assistant professor, Urban and Environmental Policy, Occidental College, April 16, 2021

Interview, Philip Jordan, vice president, BW Research, April 14, 2021

Interview, Peter Sikora, senior adviser, New York Communities for Change, April 13, 2021

Interview, Bob Keefe, executive director, Environmental Entrepreneurs, March 26, 2021

Interview, Daniel Bresette, executive director, Environmental and Energy Study Institute, April 9, 2021