Get PolitiFact in your inbox.

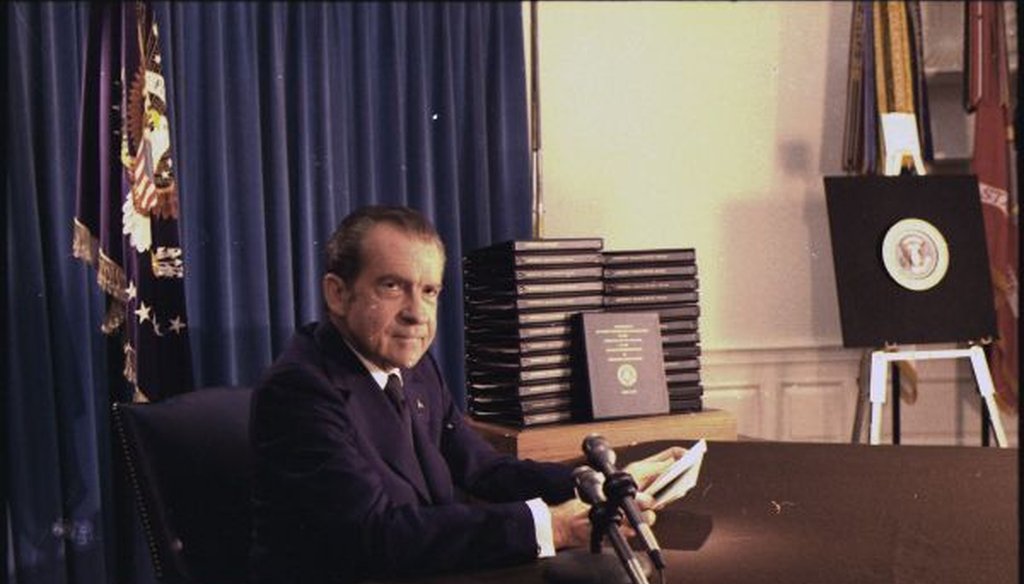

President Richard Nixon holds a press conference to release edited transcripts of secretly recorded White House conversations, April 29, 1974.

On the morning of May 12, 2017, President Donald Trump tweeted, "James Comey better hope that there are no 'tapes' of our conversations before he starts leaking to the press!"

Already primed to look at the parallels between Trump’s presidency and Richard Nixon’s, observers jumped on the suggestion that Trump could be following Nixon’s lead in secretly taping conversations in the White House. (At his daily briefing, White House Press Secretary Sean Spicer had no further comment when asked several times about whether taping had occurred.)

We wondered: Would it be within Trump’s legal rights to conduct secret taping in the White House?

The answer, apparently, is yes.

What’s the law?

Legal experts we contacted agreed that the controlling law would be that of the District of Columbia -- and D.C. law allows "one-party consent" taping. That means that taping is legal as long as one participant in the conversation is aware that a recording is being made.

"There’s no federal or D.C. law of which I’m aware that makes it illegal to unilaterally record a conversation in the District of Columbia," Stephen I. Vladeck, a professor at the University of Texas School of Law. "That’s without regard to whether such recordings might themselves be evidence of other criminal activity, but that’s another matter altogether."

Some jurisdictions require two-party consent, meaning that both parties must be aware of the taping, but the District of Columbia is not one of those. No-party consent -- essentially secret surveillance by a third party -- is typically illegal without a judicial warrant.

After the Nixon resignation, the American Bar Association issued an ethics opinion saying it was unethical for a lawyer, even when not acting as a lawyer, to secretly tape record a conversation, even if the law allowed the taping, said Ronald Rotunda, a law professor at Chapman University who was an investigator during Watergate and later an adviser to special prosecutor Kenneth Starr during the Clinton administration. But "a decade or so ago, the ABA overturned that ethics opinion," Rotunda said. (And of course Trump would not have been bound by it, since he's not a lawyer.)

Nixon's taping system

Nixon wasn’t the first president to secretly record White House conversations. The practice goes back at least as far as Franklin D. Roosevelt. John F. Kennedy used the practice as well.

"I heard, when I visited the Kennedy Library years ago, a taped phone conversation with Jack and Bobby Kennedy on one end and Mississippi Gov. Ross Barnett on the other end," Rotunda said. "They were talking about a segregation issue. Kennedy was very good and Barnett sounded like the segregationist that he was."

Kennedy’s successor, Lyndon B. Johnson, taped even more extensively than Kennedy did. (You can listen to several of these calls if you happen to visit Johnson’s Texas ranch.) But Nixon’s White House taping was unusually extensive, and -- eventually -- it put the final nail in the coffin of his presidency, once it was revealed in public testimony by former White House aide Alexander Butterfield.

Initially, Nixon didn’t install recording devices, but a year or two into his presidency, he decided to install them, said James D. Robenalt, a Cleveland lawyer who runs a continuing legal education class on Watergate and its lessons

"No one knew except for Butterfield and (chief of staff H.R.) Haldeman and some Secret Service guys," Robenalt said. White House counsel John Dean and National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger were among those who didn’t know, Robenalt said.

The taping system was quite advanced for its day, Robenalt added. The system in the Oval Office was voice-activated, and it was rigged so that it would not turn on when Nixon was away from the White House. That way it wouldn’t pick up conversations by janitorial workers or other staff when he wasn’t there.

The recorder in the Oval Office wasn’t the only one Nixon installed. He also installed one specifically for the Oval Office phone, as well as in his office in the Old Executive Office Building, in the Cabinet Room, at his Camp David retreat, and in the Lincoln Sitting Room in the private residence.

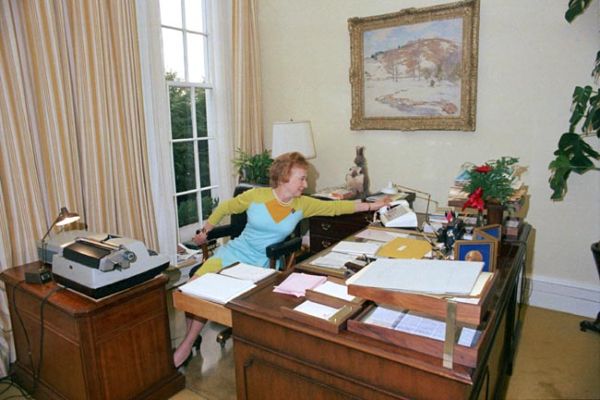

Rose Mary Woods, President Richard Nixon's secretary, demonstrates how she may have erased a portion of a tape recording known as the 18 1/2 minute gap in 1973. (Gerald R. Ford Presidential Museum)

The recorder in the Lincoln Sitting Room proved to be one of the most important for historians, Robenalt said. "He would start a fire, take out a drink and just call people," he said. "On one tape, he called (his aide) Charles Colson at 1 a.m. and ended it at 2:15 a.m., on the night before his second inauguration."

But Nixon’s recordings set the stage for his downfall.

"Nixon’s presidency was consumed by a battle for the tapes," said Ray Locker, author of Nixon's Gamble: How a President’s Own Secret Government Destroyed His Administration. "That was the reason behind the firing of Watergate special prosecutor Archibald Cox and the resignations of Attorney General Elliot Richardson and his deputy, William Ruckelshaus -- the Saturday Night Massacre. The revelation of the June 23, 1972, conversation between Nixon and H.R. Haldeman in which Nixon agreed to use the CIA to block the FBI’s investigation into the Watergate break-in is what forced Nixon to resign, because it was considered proof of obstruction of justice."

What about post-Nixon presidents?

Once the taping system was revealed to the public, Nixon’s chief of staff at the time, Alexander Haig, pulled the plug on it. Nixon was never charged with any crimes related to taping, and the experts we checked with were unaware of any policies instituted after Watergate to officially curb the practice at the White House.

That said, the price Nixon paid for installing his taping system convinced several subsequent presidents to forswear taping almost entirely, according to the 1999 book, Inside the Oval Office, by William Doyle.

Aside from two calls to foreign leaders, Gerald Ford did not record conversations while in the White House. Ford’s press secretary, Ron Nessen, said that "coming on the heels of Watergate, Ford gave very firm instructions to have any and all taping equipment removed," according to Doyle.

Jimmy Carter followed Ford’s policy. During the Camp David Middle East peace process, according to Doyle, National Security Adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski suggested taping the Israeli and Egyptian delegations to gain a diplomatic advantage for the United States. But Carter, well known for his moral beliefs, recoiled. He "shot down the proposal and did not allow any recordings to be made of any White House activity, secretly or otherwise, at any point during his presidency," Doyle wrote.

The most extensive White House taper since Nixon appears to have been Ronald Reagan. According to Doyle, deputy chief of staff Michael Deaver said that early in his administration, "Reagan was presented with the option of continuing or not continuing the phone tapings in the Oval Office for national security purposes. And obviously tapings were a very controversial subject ever since the Nixon days. But Reagan could see the value of it, not so much for history but for accuracy … and readily agreed to continue the tapings."

For most of his term, Reagan also allowed portions of closed meetings to be recorded on video, with the participants aware of that cameras were present. "Reagan, supremely comfortable with cameras and always pressed for time, would often start the meeting while the crew was still in the corner of the room shooting, and the crew stayed in the room as long as the first five or 10 minutes, sometimes longer," Doyle wrote. The 800 hours of footage was largely forgotten until Doyle was researching his book.

Despite the quantity of material, observers called Reagan’s approach less problematic than Nixon’s.

Craig Shirley, a Reagan biographer, said Reagan never would have used secret tapes as a weapon, as some saw Trump’s tweet against Comey as doing. "Threaten or attempt to blackmail a former government official? The question itself is preposterous because it never would have even crossed Reagan’s mind," Shirley said. "Nixon, yes, Trump, yes, Reagan? Morally impossible."

Reagan’s successor, George H.W. Bush, returned to the no-taping policy Ford and Carter had followed. According to Doyle, Bush’s Chief of Staff John Sununu and National Security Adviser Brent Scowcroft said that "no video or audio recordings of meetings (were made, nor) head-of-state telephone calls, nothing."

There is no hard evidence that Bill Clinton secretly taped conversations. If he had, such material would presumably have come to light during the intense investigation into his affair with White House intern Monica Lewinsky.

But there’s some remaining uncertainty. Rotunda said that the Starr investigators "subpoenaed material that was not turned over." As a result, he said, "I don’t know whether Bill Clinton or one of his aides ever secretly tape recorded anyone."

In any case, Rotunda said, "What was unusual about Nixon was the extensive tape recordings."

Our Sources

Donald Trump, tweet, May 12, 2017

Digital Media Law Project, "District of Columbia Recording Law," May 12, 2017

William Doyle, Inside the Oval Office, 1999

PolitiFact, "How similar are the Saturday Night Massacre and the Comey firing?" May 11, 2017

Email interview with Ray Locker, author of Nixon's Gamble: How a President’s Own Secret Government Destroyed His Administration, May 12, 2017

Email interview with Ronald Rotunda, law professor at Chapman University, May 12, 2017

Email interview with Jeff Shesol, former Bill Clinton speechwriter and biographer of Lyndon B. Johnson, May 12, 2017

Email interview with Stephen I. Vladeck, professor at the University of Texas School of Law, May 12, 2017

Email interview with Craig Shirley, president and CEO of Shirley & Banister Public Affairs, May 12, 2017

Interview with James D. Robenalt, attorney and creator of a continuing legal education class on Watergate and its lessons, May 12, 2017