Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

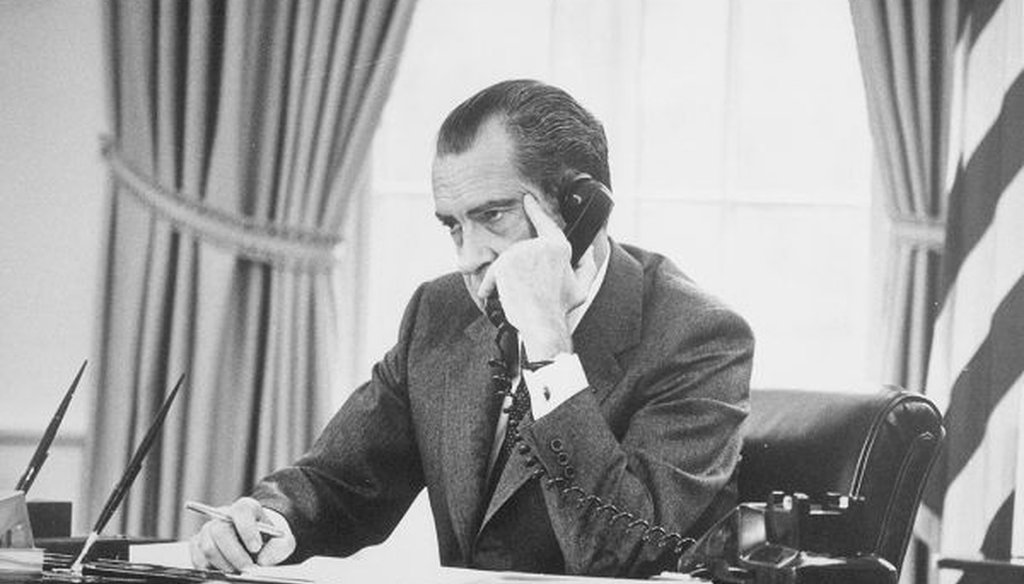

Richard Nixon in the Oval Office. (National Archives)

Americans are hearing a lot of comparisons these days between Richard Nixon and Donald Trump, particularly after news reports revealed the existence of contemporaneous notes taken by soon-to-be-fired FBI director James Comey during his conversations with Trump.

The news reports hinted at further notes that could be subpoenaed by either Congress or law enforcement, fueling speculation that these materials could help lay out a case that Trump committed obstruction of justice by seeking to quash probes into his campaign’s alleged ties to Russia.

"Asking FBI to drop an investigation is obstruction of justice," Rep. Ted Deutch, D-Fla., the ranking member of the House Committee on Ethics, tweeted. "Obstruction of justice is an impeachable offense."

We wanted to examine three key questions surrounding Trump’s legal situation.

How strong is the case for obstruction of justice at this point?

Sign up for PolitiFact texts

Much of the law surrounding this question, at least as applied to a president, is new ground. So it’s unclear how such a prosecution of Trump would play out, or whether it would meet the "beyond a reasonable doubt" standard for a criminal case.

The law dealing with obstruction of justice is governed by Title 18 of the United States Code, a set of statutes passed by Congress dealing with federal crimes and criminal procedure. Two provisions of Title 18 could provide avenues for a prosecutor pursuing charges against Trump.

One provision potentially relevant to Trump’s firing of Comey is Section 1505, which concerns the obstruction of proceedings taking place before departments, agencies and committees.

Section 1505 lays out requirements for a defendant’s actions and mental state that must be met — beyond a reasonable doubt — to reach a guilty verdict.

Under this provision, a prosecutor would have to show that through threat or force, Trump obstructed, influenced or impeded a proceeding (or attempted to do so), while he had a "corrupt" mental state.

Michael Herz of Cardozo Law School at Yeshiva University said the Supreme Court has never ruled on the narrow question of whether an FBI investigation qualifies as a "proceeding." But he believes a good argument can be made that it is.

Prosecuting Trump under Section 1505 would likely turn on why he removed Comey, Herz said. In other words, did the president act "corruptly" during the firing — defined as "acting with an improper purpose, personally or by influencing another"?

Herz said that while the president has broad authority to fire an FBI director, some grounds for dismissal would be impermissible and amount to obstruction, particularly pertaining to former National Security Adviser Michael Flynn.

"Trying to protect a criminal because he is a friend or the investigation will be personally or professional problematic for the obstructor, on the other hand, is pretty clearly an ‘improper purpose,’" he said.

Another potentially applicable section of Title 18 would be Section 1503, known as the "Omnibus Clause."

This section differs from section 1505 in some important ways.

First, whereas 1505 concerned the obstruction of agency and other proceedings, this section applies to obstructing judicial proceedings. Second, Section 1503 adds a requirement that the defendant knew about the judicial proceeding before committing the criminal act.

Beyond that, the rest of the requirements — the act itself and the mental state — generally mirror section 1505. In both instances, the defendant must have interfered (or tried to) while acting "corruptly."

Based on what we know today, a plausible case could be made that Trump met all the elements under section 1503, said James Robenalt, a lawyer at the firm Thompson Hine and an expert on Watergate.

The relevant judicial proceeding in this case would not be the FBI investigation but rather a grand jury that has reportedly been empaneled to investigate whether the business activities of Flynn broke criminal laws. News reports about federal prosecutors issuing grand jury subpoenas to Flynn associates emerged just hours before Comey’s firing.

That might be sufficient evidence for obstruction of justice. However, the case would be stronger if it also included Trump’s earlier conversations that were described in Comey’s contemporaneous notes. Those conversations would provide additional evidence of Trump's intent in urging Comey to drop the FBI’s Flynn investigation. So could the reported allegation that Trump tried to extract a loyalty oath from Comey in the administration's early days.

However, much of the discussion about possible obstruction of justice is speculative, and matters like intent are always tough to prove.

Can a sitting president be prosecuted?

Of course, none of the preceding discussion means much unless a president can actually be prosecuted. And that’s a longshot.

Officially, there has never been a binding judicial opinion on this question.

"It is unresolved," said Erwin Chemerinsky, dean of the law school at the University of California-Irvine. "The Watergate grand jury in 1974 named Richard Nixon an ‘unindicted co-conspirator’ because they did not know if they could indict a sitting president."

That said, there is a widespread assumption among legal experts that courts would rule against the idea of prosecuting a sitting president.

Why? It’s primarily due to a pair of opinions by the Office of Legal Counsel, the closely watched office within the Justice Department that advises presidential administrations on the legality of taking certain positions or actions.

The office looked at this question in 1973 and 2000, concluded on both occasions that a president could not be criminally prosecuted. Criminal prosecution, the office determined, would undermine the executive branch’s ability to perform its functions. Ultimately, "only the House of Representatives has the authority to bring charges of criminal misconduct through the constitutionally sanctioned process of impeachment," the office wrote in 2000.

Legal scholars say that while the case for presidential immunity from prosecution isn’t a slam dunk, the Office of Legal Counsel opinions carry significant weight in predicting how a federal court would handle the question if asked.

"The president can be accused of anything, but he cannot be prosecuted while in office, on the grounds that it would be a distraction from leading the government," said Susan Rose-Ackerman, a Yale Law School professor.

In the 1997 case Clinton vs. Jones, the courts ruled that President Bill Clinton could face a civil suit while still in office. (It stemmed from Paula Jones’ allegations of sexual advances when Clinton was governor of Arkansas.) But the Office of Legal Counsel made clear that the Jones ruling did not mean that it was also proper to green-light a criminal prosecution against a sitting president.

What do these developments mean for a possible impeachment proceeding?

So if a prosecution of Trump is unlikely, the main value of any evidence of criminal acts such as obstruction of justice would be as the basis of articles of impeachment drafted by lawmakers.

The Senate would hold a trial on any articles of impeachment that pass the House, with a two-thirds Senate majority needed for removal from office.

There is strong precedent for articles of impeachment involving things that sound a lot like criminal charges, even though no such charges were been made by law enforcement -- much less adjudicated in the courts. In essence, Congress weighs these quasi-criminal charges as if they were acting in the place of a court of law.

For instance, Nixon’s impeachment articles stated that, "using the powers of his high office, (he) engaged personally and through his subordinates and agents in a course of conduct or plan designed to delay, impede, and obstruct the investigation of such unlawful entry; to cover up, conceal and protect those responsible; and to conceal the existence and scope of other unlawful covert activities."

The other two articles addressed abuse of power and defiance of subpoenas. (Nixon resigned before the House could vote on them.)

Meanwhile, the two articles of impeachment that passed the House against Bill Clinton were:

• "The president provided perjurious, false and misleading testimony to the grand jury regarding the Paula Jones case and his relationship with Monica Lewinsky," and;

• "The president obstructed justice in an effort to delay, impede, cover up and conceal the existence of evidence related to the Jones case."

Floor proceedings of the U.S. Senate in session during the impeachment trial of Bill Clinton, 1999.

The role that obstruction of justice allegations played in the impeachment proceedings against both Nixon and Clinton goes a long way toward explaining why the most recent revelations are being taken so seriously. Experts say it would be easier for those seeking impeachment to be able to argue that an actual crime, such as obstruction of justice, may have been committed.

Unlike the judicial system, impeachment is ultimately a political process. A majority of lawmakers, rather than a jury or a judge, is charged with determining what constitutes a high crime or misdemeanor. And given that Republicans control both chambers for now, any impeachment of Trump seems unlikely.

"There is no chance that the House will in fact impeach Donald Trump even if it was convinced that (Comey’s notes were) the true account of his firing," Herz said. "At least, there is no chance that it will do that now. However, there’s no statute of limitations for impeachment."

Why is the lack of a ticking clock important? If Democrats take over the House in the 2018 midterm elections, they would be able to pursue impeachment without worrying about how early in Trump’s term the alleged misdeeds occurred.

Our Sources

Ted Deutch, tweet, May 16, 2017

United States Constitution, Article II, accessed May 17, 2017

Office of Legal Counsel, "A Sitting President's Amenability to Indictment and Criminal Prosecution," Oct. 16, 2000

Clinton v, Jones (1997)

Richard Nixon articles of impeachment

Bill Clinton articles of impeachment

Federal judge's moot analysis of Watergate issues, 2011

New York Times, "Comey Memo Says Trump Asked Him to End Flynn Investigation," May 16, 2017

Washington Post, "Legal analysts: Trump might have obstructed justice, if Comey’s allegation is true," May 16, 2017

New York Times, "What is Obstruction of Justice? An Often Murky Crime, Explained," May 16, 2017

Associated Press, "Q&A: Would Trump request to end Flynn probe have broken law?" May 17, 2017

Daily Beast, "James Comey’s Notes Are Trump’s Smoking Gun," May 17, 2017

Email interview with Susan Rose-Ackerman, Yale Law School professor, May 16, 2017

Email interview with Erwin Chemerinsky, dean of the law school at the University of California-Irvine, May 16, 2017

Email interview with Ray Locker, author of Nixon's Gamble: How a President’s Own Secret Government Destroyed His Administration, May 16, 2017

Email interview with Ronald Rotunda, law professor at Chapman University, May 16, 2017

Email interview with Michael Herz, law professor at Cardozo Law School at Yeshiva University, May 16, 2017

Email interview with Andrew Kent, law professor at Fordham University, May 16, 2017

Email interview with Lauren Ouziel, law professor at Temple University, May 16, 2017

Email interview with Laurence Tribe, law professor at Harvard University, May 16, 2017

Email interview with Daniel Richman, law professor at Columbia University, May 16, 2017

Email interview with Steven Vladeck, law professor at the University of Texas Austin, May 16, 2017

Email interview with Kermit Roosevelt, law professor at University of Pennsylvania, May 16, 2017

Interview with James D. Robenalt, attorney and creator of a continuing legal education class on Watergate and its lessons, May 17, 2017

Politifact Rating:

Politifact Rating: