Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

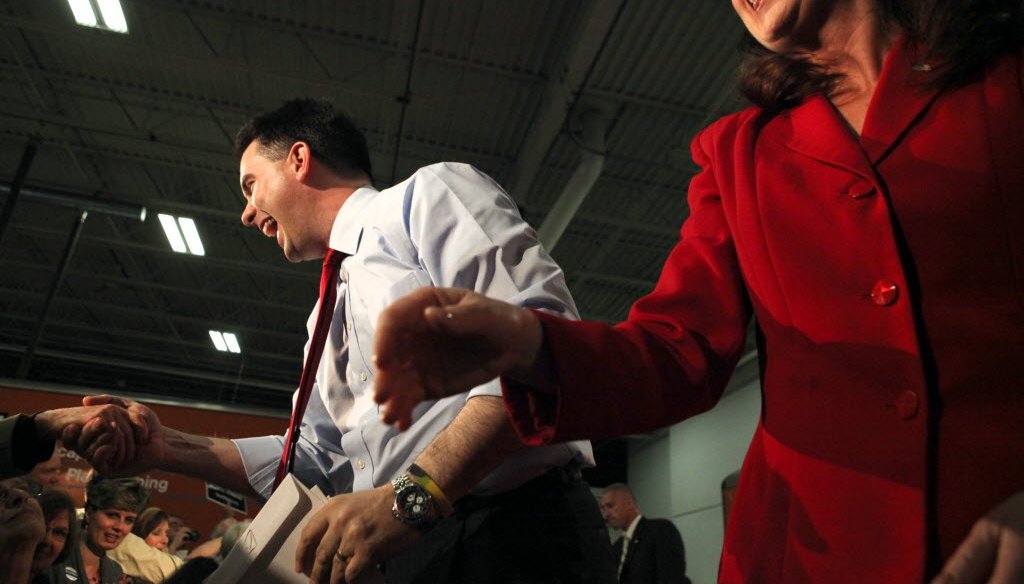

Gov. Scott Walker and Lt. Gov. Rebecca Kleefisch greet supporters at a campaign event. Both are facing recall elections June 5, 2012.

Democrats and their recall allies decry the law that has helped Gov. Scott Walker out-raise his opponents combined by $11 million dollars without regard to normal campaign contribution limits.

It’s an "outrageous loophole" and "unfair advantage" that lets Walker -- in the words of state Rep. Kelda Helen Roys, D-Madison -- "operate in lawless fashion" like it’s the Wild West.

Indeed, in early 2012 Walker raised six times more than his four challengers and raised more than he spent in the entire 2010 election.

In regular elections, statewide candidates are limited to receiving $10,000 from individuals over their term in office. But for four and a half months -- from when recall papers were filed to when the June 5 election was called -- there were no limits on donations. Two people gave him $500,000 each, and two-thirds of his total came from out of state.

To help readers sort out the rhetoric around the issue, we decided to take a closer look at this provision in state law and how it came about.

First off, there’s nothing illegal about Walker’s actions -- they are expressly permitted under a 1987 change in state campaign finance law.

Indeed, while Democrats have slammed the provision, the same state law also allows committees seeking the recall of an official to raise funds without worrying about the normal limits -- and Democratic state senators facing recalls had the same chance in the summer of 2011.

"It’s offensive to say it’s a loophole. It’s a clear statute," said Mike Wittenwyler, a Madison political law attorney. "If that’s a loophole, then the entire state statutes are a loophole."

In fact, though the change was supported by incumbents in both parties, Democrats were key to its birth in 1987 -- and state elections officials supported it at the time.

The change bubbled up through the State Elections Board during the Democratic administration of Gov. Tony Earl. It came during a period when two state senators -- Democrats Gary George and Tom Harnisch -- had been forced to use campaign funds to pay lawyers for court challenges to recall efforts against them.

State Sen. David Helbach (D-Stevens Point) inserted the change into the 1987-’89 state budget as the Legislature’s Joint Finance Committee finished its work.

Though Democrats helped maneuver the change into law, both parties backed it. The committee vote was bipartisan and unanimous and Republican Gov. Tommy Thompson -- who succeeded Earl in January 1987 -- did not veto the provision.

At the time, news reports focused on the fact that while it benefited all incumbent officeholders, the change appeared to have an immediate impact for George, a Milwaukee senator. George had campaign debts from successfully fending off a 1986 recall. (In 2003, George was recalled, and later he served prison time after pleading guilty to one count of conspiracy for accepting about $270,000 in kickbacks of legal fees paid by a social service agency.)

News accounts said the change would give incumbents under threat of recall a way to pay off legal fees incurred when challenging signatures.

The 1987 budget amendment was written to apply backwards to July 1986, allowing George to apply contributions to legal bills from his court fight over recall petitions -- without having them count against contribution limits for his next regular election, news reports said.

George told us he didn’t recall raising big-ticket contributions, and that it would be wrong to portray him as the only beneficiary of the move.

"The nature of the change was way beyond me," George said.

It was a different era, to say the least.

George, for instance, had $60,000 in legal debts from the recall. Even accounting for inflation, that amount pales in comparison to the $13 million Walker raised early in 2012, good chunks of it from over-the-normal-limit donations.

Elections then were far less costly and candidates themselves raised the most cash -- not the third party groups that dominate today.

"In the 1980s, no one was looking at the vast amounts of money than you can tap now," said Kevin Kennedy, the executive director of the state Government Accountability Board who held the same post in 1987 with what was known then as the State Elections Board.

"If I were voting on it today, I wouldn’t support it," said Peter Dohr, a Madison attorney who chaired the State Elections Board when it voted to support the move in 1986.

A two word-phrase in the law ("other expenses") allows the large donations to be used to finance TV ads during a recall signature drive, based on state election officials’ legal opinions.

Let’s take a brief look at how and why the change was made.

The push came from the Elections Board, a panel of political appointees from both parties who oversaw election regulation.

In 1986, the board had directed that campaign finance law be changed to remove normal contribution limits for expenses related to fighting a recall drive -- just as the law already did for recount expenses.

An Elections Board-backed bill directing the change had already been introduced in April 1987, months before Helbach’s budget amendment.

There was a question at the time of whether recall contributions could be regulated at all, given that state recalls were enshrined in the Wisconsin Constitution in 1926, giving the process special protections. We should also note that Kennedy didn’t favor unlimited individual contributions -- he favored a separate campaign fundraising period with the normal limits.

Documents from the 1980s show that Kennedy and the board were concerned that recalls -- unscheduled elections -- could leave incumbents at a disadvantage.

"If the recall effort is successful and a recall election is called, the incumbent is saddled with the costs of defending (against) the recall and the costs of the recall election in the same campaign period," Kennedy wrote in a Dec. 30, 1986 memo to the Elections Board.

Those stepping up to take on recalled incumbents after a successful petition drive can raise funds without being burdened by paying for the recall drive itself, Kennedy noted. (Of course, the challengers had to obey the normal contribution limits -- then and now.)

Kennedy noted in an interview with us that the law allowing unlimited-size donations also applies to the political committees who fund petition drives to recall an official. They can raise the jumbo gifts as well for that limited period, though elections officials say they have seen no evidence they did so.

"The law is written to benefit both sides" during the petition drive, Kennedy said.

Let’s bring this back to present day and cover a few important points.

Walker cannot use donations above the normal $10,000 limit for campaign expenses during the actual election period -- from March 30 through June 5. He has to use the money for expenses related to challenging the recall drive, which ran from Nov. 15, 2011 to March 30, 2012.

So if he raised more over-the-limit funds than his expenses for TV ads and mailers during the recall drive, he will have to return the money or give it to other officials’ campaign funds or to charity. That accounting has not yet been done.

Contributions the governor takes in now during the recall election period have to be within the usual limits.

Given the realities of modern campaigning, does the 1987 law need to be reviewed?

Yes, the appearance of corruption is too great, said Mike McCabe, executive director of the nonprofit Wisconsin Democracy Campaign, which tracks money in state politics. Roys has introduced a bill to subject recall donations to the usual limits.

Kennedy, though, cautioned that legal issues could block change, given that some legal experts argue that donations during recall drives need not even be disclosed.

"We’d have to look at it carefully," he said, noting the constitutional issues.

(You can comment on this story on the Journal Sentinel's webpage.)

Our Sources

Phone interview with Kevin Kennedy, director and general counsel, Wisconsin Government Accountability Board, May 3-4, 2012

Phone interview, Gary George, former state senator, May 3, 2012

Phone interview with Peter Dohr, former State Elections Board chairman, May 3, 2012

Phone interview with Reid Magney, spokesman, Government Accountability Board, May 3, 2012

Historical research by Michael Keane and Dan Ritsche, senior legislative analysts, Wisconsin Legislative Reference Bureau, May 3-4, 2012

Phone interview with Mike Wittenwyler, Madison attorney, May 2, 2012

Phone interview with Rep. Kelda Helen Roys, Madison Democrat, May 2, 2012

Phone interview with Mike McCabe, executive director, Wisconsin Democracy Campaign, May 2, 2012

Phone interview with Michael Buelow, research director, Wisconsin Democracy Campaign, May 2, 2012

Government Accountability Board, Recall Expense Funds memo, March 15, 2011

Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, "Walker raises $13 million since January," April 30, 2012

Milwaukee Sentinel, "Late budget provision aids George on recall," Sept. 3, 1987 (part 1) (part 2)

Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, "Voters give George the boot," Oct. 22, 2003