Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

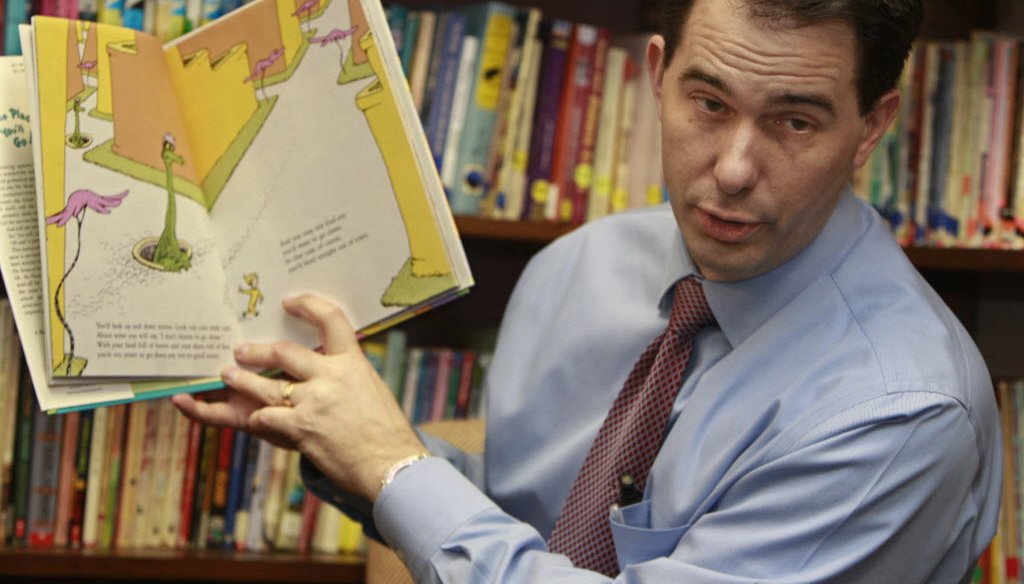

Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker has defended his record on education in the face of criticism over his 2011-13 budget

Gov. Scott Walker and his recall critics may as well be on different planets when it comes to describing how local schools fared under his budget.

Walker tells audiences that most schools got far more savings from his controversial collective bargaining limits -- money-saving "tools" in Walker’s phrasing -- than they suffered in cuts from his budget.

Democratic Party officials and their allies say schools all over the state suffered "devastating" aid cuts, and Walker recall opponent Tom Barrett says education was "gutted."

After examining the issue and doing extensive interviews with 17 Milwaukee-area school districts, it’s clear both sides are exaggerating.

But answering the bottom line question of whether the "tools" outweighed the cuts is elusive.

Even if every school district were surveyed, the differing ways in which higher employee payments for health care are scored makes an apples-to-apples comparison impossible. What’s more, some districts have not yet come under the law at all, because workers had union contracts in place at the time that did not expire.

This is the first in a series of PolitiFact Wisconsin stories aimed at helping voters in the June 5, 2012, recall election get behind the rhetoric of the campaign. Upcoming pieces will look at the WEA Trust, in-state vs. out-of-state contributions and more. We’ll also continue to do Truth-O-Meter items on specific claims.

Any look at the questions surrounding this issue center, of course, on the 2011-’13 budget, advanced by Walker and the GOP-held Legislature.

To help close a $3.6 billion deficit, Walker imposed a 5.5 percent reduction in school spending and cut $792 million in aid to schools.

In a separate move -- now known as Act 10 -- he also sharply curtailed collective bargaining for most public employees, mandating a pension contribution that equalled 5.8 percent of salary in 2011, and allowing districts to collect higher contributions from employees for health care costs.

Did Walker’s collective bargaining move make schools’ budgets whole -- and more?

That depends on which district you’re talking about.

The experience of districts varied widely in year one, based on whether they had long-term labor contracts in place, how much they already were charging employees for health insurance, their enrollment trends, their fiscal situation, local political factors -- and, in some cases, just plain luck.

If their labor contracts were expiring, districts got the power to impose -- without negotiating with unions -- higher health premium shares on employees, as well as shift pension contributions to workers, and cut other staffing costs.

Because Walker’s union limits and his budget cuts came so quickly, districts were to some extent at the mercy of past decisions. Some rushed to extend labor contracts before the budget passed, limiting in theory the concessions they could get, though most mirrored Act 10 pretty closely.

In the Milwaukee area, what sorts of districts were left out of big Act 10 savings?

Three examples:

The Fox Point-Bayside school district, in two small Milwaukee North Shore suburbs, had signed a new labor contract with educators about a month before Walker’s inauguration, and three months before he introduced his budget. It was left to fill a $689,000 funding gap.

With property tax levies virtually frozen by the state, that left Fox Point with little choice but to lay off some teachers and aides, leave teaching vacancies created by retirements unfilled and reduce support for instruction and technology, among other programs, officials there said.

The administration sought to reopen the contract once Walker’s plan emerged. But informal talks with the teachers union fizzled, in part because teachers for years had paid a health-care premium contribution close to what Walker pushed.

On a much larger scale, Milwaukee Public Schools was in a similar spot, and wound up cutting 7 percent of its staff, including 300-plus teachers -- though declining enrollment also factored in.

MPS later unsuccessfully sought to re-open an existing multi-year contract with teachers. The district did get a small amount of Act 10 savings by putting in a pension contribution from non-union staff.

Good timing helped some districts that had existing contracts.

Glendale-River Hills, for instance, didn’t try to re-open labor contracts it had signed after Walker’s election but shortly before he took office. That’s because it had $600,000 in unused property tax levy in hand from a referendum. So it didn’t need savings from Walker’s tools to balance its budget, which happened to take a $600,000 cut in the budget.

Of the 17 districts we checked, 13 fell short of offsetting their cuts with savings directly from Act 10 -- or savings negotiated with unions under the influence of Act 10.

That sounds like trouble for those 13 districts. Did Walker’s law leave all of them short?

Not exactly.

In some cases, districts made conscious decisions not to completely offset their revenue losses with health insurance savings enabled by Act 10. Or they negotiated particular payment levels with unions instead of imposing a level.

Greenfield schools, for example, declined to ask employees to pay more than the 10 percent health insurance premium share they already were paying. (Act 10 pushed the share to 12.6 percent for state employees and some local employees, and that became a benchmark for what school districts might do).

Menomonee Falls negotiated a new labor deal with teachers while Act 10 was hung up in the courts. The deal called for the employee premium share to rise from 5 percent to 8 percent in the first year, with a second increase phased in the second year -- to 11.5 percent.

Menomonee Falls officials said they wanted to ease the financial burden of the change by spreading it out. Likewise, some districts said they don’t want to squash morale by putting too much on employees all at once.

Greenfield Superintendent Conrad Farner said it was partly about competition for employees -- his district already was at one of the highest premium shares in the area.

In Farner’s view, Greenfield "kind of got "punished" for already getting higher contributions through traditional negotiations."

Some districts were much lower. In fact one, St. Francis schools, was charging nothing in premiums, then went to 10 percent after Act 10, a big savings.

Shorewood bumped its employee share up to the 12.6 percent mark Walker had established but didn’t want to go beyond that.

"You don’t want your good teachers looking elsewhere," said Mark Boehlke, the district’s business manager.

How many districts lost teaching staff in 2011-’12?

We found 11 of 17 districts we surveyed did -- with budget cuts, enrollment drops and teacher retirements behind the trend. The range was 1 percent to 7 percent.

In some cases, an increase in retirements fueled the decrease, as teachers fearful of the possible loss of post-retirement health insurance and other benefits left earlier than anticipated.

For many districts, this led to cost savings because they could hire younger teachers at a much lower cost.

It’s a major reason why some districts in our survey appear to fall short through Walker’s "tools" of offsetting their revenue losses -- but in reality got all they needed in the wake of Act 10 to balance their budgets.

Brown Deer is an example. On paper, the district covered about 80 percent of the state reductions with Act 10 savings.

But before Brown Deer even calculated how far to go on health insurance based on the changes made possible by Walker, the district realized it would have 11 retiring staff members who would be replaced by less senior teachers. That saved the district $207,000.

The staffing savings from retirements, along with other factors, meant Brown Deer did not have to get all the pension and health savings under Act 10 in order to balance its budget, said Emily Koczela, Brown Deer’s director of finance. (Other districts told us the same thing.)

Koczela said Act 10 allowed Brown Deer to revive a referendum on major building improvements that were long neglected and having a negative effect on the whole district.

"So we feel as though the impact was almost the difference between going on or going under," Koczela said.

Statewide, in the 2011-’12 school year, school staffing fell in about three-fourths of school districts, and 2.3 percent statewide, a Department of Public Instruction report found.

About half the total loss of 2,312 school employees was concentrated in a handful of urban school districts, including more than 600 in Milwaukee alone.

If districts fell short from savings on pension and health insurance, what else did they do to balance budgets?

Whitnall schools in south suburban Milwaukee dipped into reserves to balance the budget and pay off most of its debt, easing the impact of the budget limits. The district added staff and cut property taxes.

Menomonee Falls negotiated the end of some educator pay for extra duties, a move made by multiple districts.

Elmbrook revamped its course schedule, increasing activity fees and reducing capital improvements, among other changes. Elmbrook offset most of its budget gap through Act 10 savings on employee benefits.

Most districts we talked to delayed or denied across-the-board raises, in part pending labor negotiations over the one remaining subject they can bargain on -- base wages.

What about those districts that completely offset their losses in his budget? How did they do it?

Two examples:

Wauwatosa, where Walker’s children attend, froze pay and introduced a high-deductible health plan in addition to the pension savings. The district reduced staff, but Superintendent Phil Ertl said that was due to enrollment changes.

Greendale, with rising enrollment that helps its state aid picture, got $1 million more in savings from Act 10 than its revenue reduction under the state budget.

The pension contribution from employees, by itself, was enough to more than cover the losses. The district also got savings from higher health insurance premium shares for some workers, eliminating teacher "step" increases for years of service and other health insurance changes.

Staffing there went up slightly, and property taxes went down a bit.

Aside from pay and benefit cuts, did teachers take any other compensation cuts?

Several districts we surveyed said they had increased teacher class loads or other duties. They got the authority to change workload, without collective bargaining, in Act 10 -- or in some cases negotiated it into contract extensions they chose to sign with their unions.

In some cases this allowed budget savings because fewer employees were needed or special payments for extra duties were ended or suspended.

For example, Brown Deer teachers are teaching one extra class period.

The state’s largest teachers’ union, the Wisconsin Education Association Council, argues that teachers will have less time to work one on one with students.

"It’s not all dollars and cents when it comes to the impact," said Christina Brey, WEAC’s spokesman.

What about school property taxes? Did districts jack them up to cover the cuts in the state budget?

No.

The state budget actually specifically limited this option, in an effort to prevent districts from simply making local taxpayers pick up the lost aid. The budget reduced what schools could raise from state aid and local property taxes by $441 million in the 2011-’12 school year.

Only a few districts in our survey, including Milwaukee Public Schools, raised its property tax levy in 2011-’12 from the year before.

The rest cut the levy or held it steady. That mirrors the statewide picture. Statewide, school property tax levies actually went down, collectively -- and 60 percent of all districts cut their levy. That was a big turnaround from 2010, when 80 percent increased their levy, state figures show.

When we hear politicians issue charges and counter-charges about school funding, what should we keep in mind?

The devil’s in the details.

Either side can make claims based on surface-level stats, but only your local school officials can explain the true impact.

Intangibles such as declining teacher morale can’t be measured, though several districts mentioned it as a concern. Administrators at a couple districts, conversely, reported increased cooperation with rank and file teachers.

Walker is on target when he says districts who used the "tools" could more than offset the cuts. It’s true, at least on paper, because districts could charge their employees 100 percent of health care costs if they wanted.

Obviously that’s not realistic, and not all districts were in a position to use the tools at all because of labor deals.

Critics of Walker’s moves were correct in saying that school staffing cuts were worse under Walker than under his predecessor.

But at least a third of districts saw staffing increases, stayed steady or had very modest staffing reductions, and it’s useful to remember that enrollment declines are behind some of the staff reductions.

Our Sources

Interview with Brown Deer Schools director of finance, Emily Koczela, April-May, 2012

Interview with Whitefish Bay Schools district administrator Mary Gavigan, May 2012

Interview with Shawn Yde, director of business services, Whitefish Bay schools, May 2012

Interview with Germantown Schools district administrator Susan Borden, May 2012

Interview with Greenfield Schools Superintendent Conrad Farner, May 2012

Interview with St. Francis Schools business manager Julie Kelly, April 2012

Interview with Milwaukee Public Schools spokesperson Roseann St. Aubin, April-May 2012

Interview with Fox Point Schools director of business services Amy Kohl, April 2012

Interview with Rachel Boechler, Fox Point-Bayside schools, District Administrator, April 2012

Interview with Keith Brightman, assistant superintendent for finance and operations, Elmbrook Schools, April 2012

Interview with Deborah Rouse, director of business services, West Allis-West Milwaukee Schools, April-May 2012

Interview with Greendale Schools officials Bill Hughes, superintendent, and Erin Green, director of business services, April 2012

Interview with Shorewood Schools director of business services Mark Boehlke, April 2012

Interview with Patricia Deklotz, Kettle Moraine Schools Superintendent, April 2012

Interview with Doug Johnson, Whitnall Schools business manager, April 2012

Interview with Menomonee Falls Schools Superintendent Patricia Fagan Greco, and Jeffrey Gross, director of business services, May 2012

Interview with Oak Creek-Franklin Schools Superintendent Sara Burmeister, April 2012

Interview with Mark Smits, Hartford Schools, district administrator, April 2012

Interview with Larry Smalley, Glendale-River Hills Schools, district administrator, April 2012

Interview with Blaise Paul, director of business services, South Milwaukee schools, April-May 2012

Interview with John Johnson, director of Education Information Services, Department of Public Instruction, April-May 2012

Interview with Brian Pahnke, assistant state superintendent, Department of Public Instruction, April-May 2012

Interview with Christina Brey, spokesperson for Wisconsin Education Association Council, May 2012

Interview with Laura Rose, deputy director, Wisconsin Legislature’s Legislative Council, May 2012

Interview with Dan Rossmiller, director of government relations, Wisconsin Association of School Boards, May 2012

Interview with Dave Loppnow, program supervisor, Education and Building Program, Wisconsin Legislative Fiscal Bureau, April 2012

Interview, Mark Conforti, teacher and chief negotiator for Fox Point-Bayside chapter of North Shore United Educators, May 17, 2012