Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

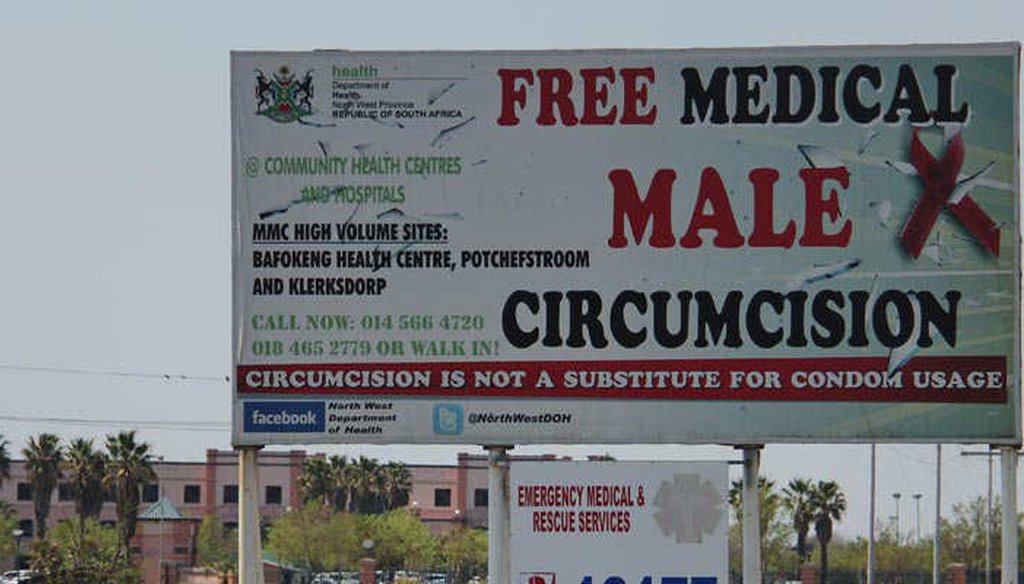

A billboard advertises medical male circumcision in South Africa (Avert)

A bit over a decade ago, AIDS researchers tested a new approach to reducing the spread of HIV -- circumcising young adult men. Today in South Africa alone, over 2.5 million men have undergone the procedure. Across Sub-Saharan Africa, the total is well over 6 million.

When the first evidence emerged that removing the foreskin might help, the international community rapidly signed on.

By 2007, the World Health Organization and the United Nations AIDS program endorsed the procedure. In 2011, the White House and UNAIDS said spending $1.5 billion by 2015 would produce $16.5 billion in savings a decade later. (The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation helped finance the expansion. The foundation also supports PolitiFact.)

But voluntary medical male circumcision has its critics. We found one skeptical note from Brian Earp, a noted ethicist who divides his time between the University of Oxford and the Hastings Center Bioethics Research Institute. Earp’s specific critique raised a fundamental question about one of the bedrock assumptions of epidemiology and public health.

Earp challenged the notion that a small change can produce a big effect.

"A handful of circumcision advocates have recently begun haranguing the global health community to adopt widespread foreskin-removal as a way to fight AIDS," Earp wrote in a 2012 blog post. He went on to relay doubts from other researchers about the real meaning of the original studies on which the grand strategy was based.

Before we look at Earp’s argument, let’s look at the initial research.

The core studies

In 2005, researchers recruited over 3,000 18- to 24-year-old uncircumcised men in a community near Johannesburg, South Africa. Half agreed to have their foreskins removed at the start of the experiment and the rest were given the option to have the procedure at the end. All were tracked for HIV infection.

After about 18 months, researchers found very few HIV infections in either group. Among those who were circumcised, there were 20 infections, compared to 49 among the control group. But that difference was deemed significant.

The headline summary was that circumcision reduced the risk of transmission from an infected woman by 60 percent.

When health officials saw that two other controlled studies in Uganda and Kenya produced similar results, there was push to scale up voluntary medical male circumcision in the nations most at risk in Eastern and Southern Africa.

The opposing view

Earp and the critics he cited focused on the low rates of HIV infection in either group. They added up the outcomes of all three studies (an approach which experts tell us raises methodology issues) and saw that the rate of new infections in the treatment group was 1.18 percent and the rate in the control group was 2.49 percent.

To them, and Earp, to say this amounted to a 60 percent reduction was misleading. Converting the difference into a percentage "generates a big-seeming number," they said, but there was less to this than meets the eye.

"The absolute decrease in HIV infection between the treatment and control groups in these experiments was just 1.31 percent, which is likely to have no appreciable effect at the demographic level," they said.

While there’s growing evidence about three years later that in fact, voluntary medical male circumcision helps rein in AIDS, our interest as fact-checkers is not whether the strategy works. We are focused on Earp’s basic point about epidemiology. Would an absolute decline of 1.31 percent have no significant impact on the spread of a disease through a community?

Epidemiology 101

Earp welcomed our questions and emphasized that he should not be cited as an expert in epidemiology.

The first thing to note is that we are dealing with the rate at which people get infected. That’s called the incidence rate and it’s all about new cases. So if you have 100 people in a business and two of them get the flu in the course of a year, the incidence rate is 2 percent for the year. If at the start of the year, all of them get flu shots and only one person gets the flu, the incidence rate has fallen to 1 percent.

In absolute terms, there was a one percentage point difference. In relative terms, the flu shots reduced the incidence rate by 50 percent. The importance of that one point difference, or the 50 percent change, lies at the heart of Earp’s objection. He didn’t say the 60 percent or 1.31 percent numbers weren’t real. He said they were unlikely to make a difference.

We took Earp’s point to Michael Stoto, a statistician and epidemiologist at Georgetown University. Stoto has done no work on voluntary medical male circumcision. Our discussion was purely about the way the numbers play out.

Stoto said under the right circumstances, the 1.31 percent absolute decline and a 60 percent relative decline would be "a big deal."

"If you have a lot of people at risk, then over the whole population, the impact can be substantial," Stoto said.

AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa fits those criteria. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, in 2013, there were over 25 million people living with AIDS and each year, 1.4 million new cases. The push for medical male circumcision has rolled out in 14 countries across the region.

For 2012, South Africa estimated it by itself had 145,000 new infections among men 15 to 49 years old. Circumcision, if you agree with the studies, could have prevented about 43,000 of those cases.

The point is, given enough people at risk, a small change in the absolute incidence rate can add up.

The positive impacts multiply beyond the men who avoid getting infected, said Ronald Gray, professor of epidemiology at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Gray has been deeply involved in researching the efficacy of circumcision in the fight against HIV/AIDS.

"With infectious disease, once you start controlling it, you get a broader benefit because there's less infection circulating," Gray told us. "As male incidence rates decline, fewer women are exposed to infected partners, reducing female infections. This will further reduce future male exposures."

Mathematical models show how that dynamic might affect the countries in Eastern and Southern Africa where HIV infection is high and circumcision rates are low. Results published in 2011 predicted that if the effort reached 80 percent of the men through 2025, those nations would avoid about 3.3 million infections.

Theory versus practice

Earp said the core argument against the circumcision initiative was that the results of controlled studies would not be replicated in the real world. He put us in touch with Michel Garenne, a demographer at the Pasteur Institute in Paris, who drove Earp’s thinking on this.

Garenne told us he has given up pushing back against the "massive irrational propaganda for medical male circumcision." However, he said his work in Africa convinced him that circumcision had no bearing on HIV infection.

"In a comprehensive analysis of all African countries for which data were available, based on large representative samples, there was no difference of HIV prevalence among circumcised and uncircumcised groups," Garenne said.

The response from the medical community is that not all circumcisions are the same. In some traditional settings, it is done as puberty rite in which very little of the foreskin is removed and young men are encouraged to have sex before the wound heals. An open wound would offer an easier pathway for infection.

With medical circumcision, there is counseling on a range of safe-sex practices and follow-up to promote avoidance of intercourse for at least six weeks after the procedure.

Daniel Halperin, an adjunct professor in public health at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, told PolitiFact that "there is not, nor has ever been, a single country in the world where almost all men are circumcised, and the HIV rate is above about 5 percent." (That is a prevalence rate, which captures the fraction of people infected at a given time.)

Garenne also said that men who engage in high-risk behavior won’t change their ways.

"All will become eventually infected, whatever their medical male circumcision status," Garenne said.

But even if that were true, Stoto at Georgetown said the procedure could still be effective.

"If you delay somebody getting HIV for three years, that’s a big deal," he said. "It means some people (their partners) got away without being infected."

Real world results

The Rakai District in Uganda is one of the most closely followed communities for HIV in Africa. Ugandan and American public health researchers have been engage there since 1999. They started testing medical male circumcision in 2004 and in 2008 expanded the program with money from Washington. They focused on non-Muslim men because among Muslims, circumcision is the norm.

The researchers recently assessed what happened. By 2011, nearly a quarter of non-Muslim men between 15 and 49 years old had been circumcised. They found that for every 10 percent increase in circumcision rates, the incidence rate for HIV dropped 15 percent.

That is the sort of shift the early research and epidemiological models predicted.

A small drop in the rate of new infections adds up to deliver a significant reduction.

Our Sources

University of Oxford, Practical Ethics, A fatal irony: Why the "circumcision solution" to the AIDS epidemic in Africa may increase transmission of HIV, May 22, 2012

World Health Organization, Voluntary medical male circumcision for HIV prevention, July 2012

PLOS, Assessing Voluntary Medical Male Circumcision for HIV Prevention in a Unprecendented Public Health Intervention, May 6, 2014

Quackdown, Getting circumcision science right in the media, Aug. 12, 2012

Journal of Law and Medicine, Sub-Saharan African randomized clinical trials into male circumcision and HIV transmission: Methodological, ethical and legal concerns, 2011

PLOS Medicine, Voluntary Medical Male Circumcision: Modeling the Impact and Cost of Expanding Male Circumcision for HIV Prevention in Eastern and Southern Africa, Nov. 29, 2011

PLOS One, Understanding the Impact of Male Circumcision Interventions on the Spread of HIV in Southern Africa, May 21, 2008

PLOS Medicine, Randomized, Controlled Intervention Trial of Male Circumcision for Reduction of HIV Infection Risk: The ANRS 1265 Trial, Oct. 25, 2005

African Journal of AIDS Research, Long-term population effect of male circumcision in generalised HIV epidemics in sub-Saharan Africa, 2008

Proceedings of the10th International Symposium on Circumcision, Genital integrity and Human rights, Mass campaigns of male circumcision for HIV control in Africa: Clinical efficacy, Population effectiveness, Political issues, April 14, 2009

PLOS, Male circumcision and HIV control in Africa, January 2006

Human Science Research Council, South African National HIV Prevalence, Incidence and Behaviour Survey, 2012, 2014

South African Medical Journal, The medical proof doesn’t get much better than VMMC, 2012

Epidemiological Research and Information Center, Incidence vs. Prevalence

Marie Stopes South Africa, Medical male circumcision

Journal of Law and Medicine, Criticisms of African trials fail to withstand scrutiny: Male circumcision does prevent HIV infection, 2012

HIV/AIDS, Scaling-up voluntary medical male circumcision – what have we learned?, Oct. 8, 2014

World Health Organization, Progress Brief - Voluntary medical male circumcision for HIV prevention in priority countries of East and Southern Africa, July 2014

Email interview, Brian Earp, visiting scholar, Hastings Center Bioethics Research Institute, Feb. 23, 2016

Interview, Michael Stoto, professor, Health Systems Administration, Georgetown University, Feb. 22, 2016

Email interview, Michel Garenne, demographer, Pasteur Institute, Jan. 27, 2016

Interview, Ronald Gray, professor of epidemiology, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Feb. 18, 2016

Interview, M. Kate Grabowski, assistant scientist, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Feb. 18, 2013

Email interview, Francois Venter, associate professor, Department of Medicine, University of the Witwatersrand, Jan. 23, 2016

Email interview, Daniel Halperin, adjunct professor in public health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Jan 27, 2016