Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

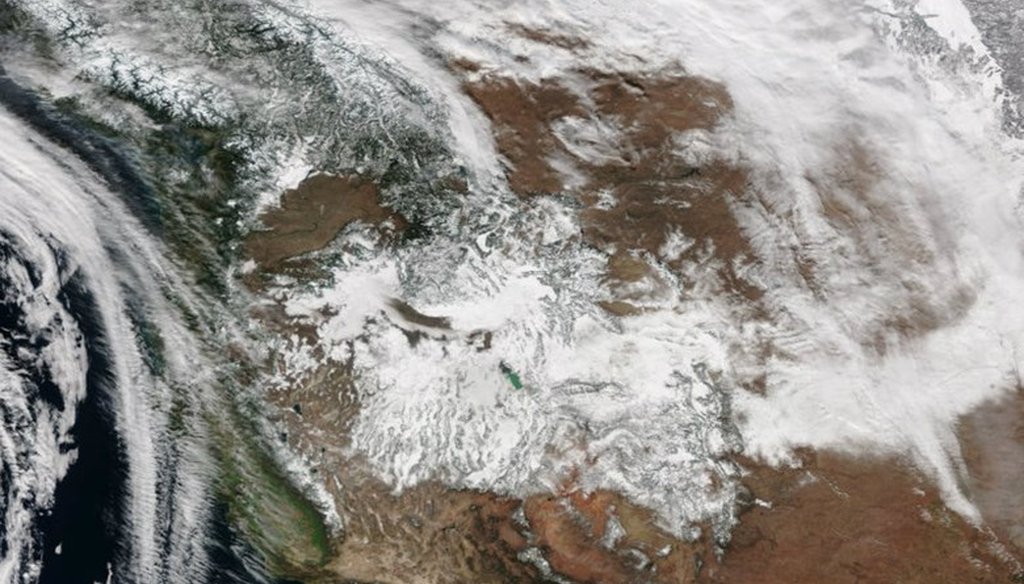

January brought abundant snow to the Sierra Nevada, but February has been mostly dry. A view of true-color imagery of the snow covering the Western U.S. from NOAA Satellite and Information Service. NOAA / Courtesy

California’s soggy start to winter had many predicting the end of the state’s record drought.

Myths and overstatements popped up like weeds after winter rain.

Some said El Niño’s powerful storms could wash away the drought by spring. Others said the state couldn’t officially declare an end to the drought until reservoirs filled up. And then there were questions about whether an official drought-ending declaration could only come from California Gov. Jerry Brown.

To determine the truth of these ‘water cooler’ statements, we contacted a half dozen climate and policy experts. The claims below aren’t attributed to specific speakers, and they aren’t rated on our Truth-O-Meter. But we figured it’s worth busting some myths.

Sign up for PolitiFact texts

1) All this rain from El Niño will definitely bust the drought.

Experts say there’s a small chance, but it’s not likely.

The prolonged drought has left the northern Sierra Nevada with a rainfall deficit of about 30 inches. As of early February, this winter’s storms had delivered about 110 percent of normal precipitation in that region, home to the state’s largest reservoirs. It’s a good start, but well behind the pace needed to end the drought.

And that was before this month’s dry spell.

To wipe away the shortfall, the state would need to get an additional 80 inches of rain in the northern Sierra before October -- on top of the nearly 33 inches that have fallen since last fall. That’s the amount of precipitation needed to close the gap and maintain an average year.

"It’s really going to take multiple years of above normal precipitation to get safely out of the drought," said Alan Haynes, a hydrologist at the National Weather Service in Sacramento.

But has a region in California ever had more than 100 inches of rain in one water year, which runs from October through September? No. Haynes said the biggest rain year on record was the El Niño-driven storms of 1982-83, which delivered about 80 inches to the northern Sierra.

"Some of the folks that watch El Niño are prophesizing rather large dumps of rain in the next few months," said Maury Roos, the state’s chief hydrologist. "So, it’s possible" that El Niño could end the drought, "if they’re right and the storms do materialize."

Possible, perhaps, but not very likely.

2) Only Gov. Jerry Brown can declare California’s drought over.

Politically, he’s probably the guy. But it’s more complicated.

The governor didn’t actually declare the drought’s start, which scientists say began during the 2012-13 water year. What Brown did is proclaim a State of Emergency in January 2014 due to the drought’s impact on California’s farms and its tinder dry forests. His proclamation allowed drought relief funds to flow, and gave the state power to restrict water use.

The experts we spoke with said the most likely scenario is that Brown will be the one to lift the emergency. But he’s not the only one with that power. The Legislature could pass a law to do it. A judge could order it removed. Or the federal government could flex its power.

But unless one of those players steps forward, it’ll be up to Brown. Of course, if the drought drags on beyond 2018, California’s next governor might be the one to make that move.

So when would the governor act? He’ll likely wait until the drought’s impacts have diminished, said Jeanine Jones, the state’s deputy drought manager. Issues to be considered: Are rural wells able to pump water again? Do farms, cities and streams have the water they need?

Even after the emergency is lifted, Jones added, California’s water use restrictions won’t necessarily go away. Those limits have their own timelines set by the state water board, which recently voted to extend them through October.

Asked who has the ultimate authority to end the drought, Jones replied: "Really, it’s Mother Nature."

3) Once California’s reservoirs fill up, the drought is over.

That’s part of the answer, but it’s not set in stone.

California has no legal definition for what a drought is or when one might be over. Instead, Chief Hydrologist Maury Roos said, one of three conditions typically must be met:

- Statewide reservoir storage would need to be at 90 percent of average levels

- Predictions for runoff would need to be 110 percent of average

- Or reservoirs on the four main rivers in the Sacramento River basin would have to reach flood control stage

"There is no official criteria. In a way, I guess you could say it’s over when the governor says it is," Roos said with a chuckle.

Several experts added that filling California’s surface reservoirs would only address part of the drought’s impact.

Replenishing the vast amounts of groundwater pumped during the drought could take decades. In areas where the soil has collapsed due to large amounts of pumping, it may not be possible to recharge underground aquifers.

In parts of the southern San Joaquin Valley, "you might not be able to refill the groundwater that’s been overdrafted," said Jay Lund, a UC Davis environmental engineering professor. "They might never refill, actually, from this drought."

In this April 28, 2015 AP photo, Frank Gehrke, chief of the California Cooperative Snow Surveys Program for the Department of Water Resources, checks the depth of the snow pack as he does a snow survey at Leavitt Lake near Bridgeport Calif.

In this April 28, 2015 AP photo, Frank Gehrke, chief of the California Cooperative Snow Surveys Program for the Department of Water Resources, checks the depth of the snow pack as he does a snow survey at Leavitt Lake near Bridgeport Calif.

In this Feb. 14, 2014, AP photo, morning traffic makes its way toward downtown Los Angeles along the Hollywood Freeway past an electronic sign warning of severe drought.

Our Sources

Phone interview, Alan Haynes, hydrologist, National Weather Service, Jan. 7, 2016

Phone interview, Maury Roos, chief hydrologist, California Department of Water Resources, Jan. 7, 2016

Phone interview, Jay Lund, Professor of Environmental Engineering, UC Davis, Jan. 8, 2016

Phone interview, Michael Anderson, state climatologist, California Department of Water Resources, Jan. 8, 2016

Phone interview, Nancy Vogel, spokeswoman, California Natural Resources Agency, Feb. 8, 2016

Phone interview, Jeanine Jones, deputy drought manager, California Department of Water Resources, Feb. 8, 2016

Phone interview, Kip Lipper, senior policy analyst, Office of the California Senate ProTem, Feb. 9, 2016

San Gabriel Valley Tribune, news article, "How much rain will it take to end California’s drought?" Sept. 20, 2015

Sacramento Bee, news article, "Is the drought over? No – but December snow survey is good news for California," Dec. 30, 2015

Governor Jerry Brown, drought State of Emergency declaration, Jan. 17, 2014

California Department of Water Resources, report, "California’s Most Significant Droughts: Comparing Historical and Recent Conditions," February 2015