Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

Can the president tell the Justice Department what to do? And if so, to what extent?

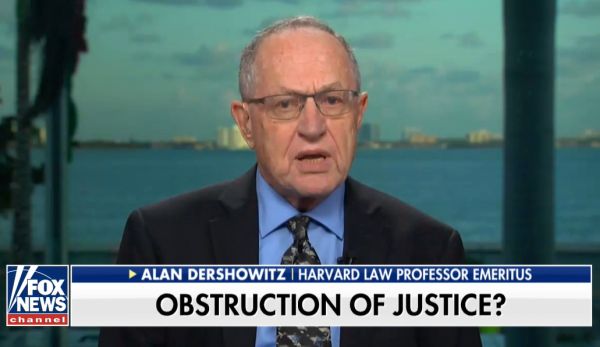

These constitutional questions exploded in the worlds of social media and punditry as soon as President Donald Trump took to Twitter to tout an appearance by Harvard University emeritus law professor Alan Dershowitz on Fox & Friends.

Dershowitz rejected the notion that Trump may have obstructed justice on behalf of his former national security adviser, Michael Flynn, when he told then-FBI director James Comey that he hoped Comey "could see your way clear to letting this go," according to Comey’s recollection.

The president, Dershowitz said, has a "constitutional authority to tell the Justice Department who to investigate, who not to investigate. That's what Thomas Jefferson did, that's what Lincoln did, that's what Roosevelt did. We have precedents that clearly establish that."

Sign up for PolitiFact texts

Several legal scholars and historians said that was, at best, an exaggeration, saying that Dershowitz’s specific examples about Jefferson, Lincoln and Franklin Roosevelt aren’t really comparable to the allegations against Trump.

Before we go any further, it’s important to note that there is sharp disagreement about whether Trump actually violated the obstruction-of-justice law — or, for that matter, whether the president has committed any impeachable offenses, which would not necessarily require a specifically criminal action.

Here, we wanted to look at whether Dershowitz is right about whether the president can tell the Justice Department what to do, and whether previous presidents did similar things.

We found that there’s some literal truth here but also some significant missing context. We’re laying out what we found and letting readers decide for themselves.

Alan Dershowitz on Fox & Friends.

Can the president tell the Justice Department what to do?

The Justice Department and the FBI do operate under the president’s authority, as set forth in Article II of the Constitution. Most experts, however, agreed that there are some limits on the president’s powers.

"It is not the case that the president has the authority to supervise the discretionary acts of all executive branch officials," said Kermit Roosevelt, a law professor at the University of Pennsylvania. "His duty is to take care that the laws are faithfully executed, not to execute them himself."

He cited an 1838 Supreme Court case in which the justices ruled that Congress can impose duties on officials and "in such cases, the duty and responsibility grow out of and are subject to the control of the law, and not to the direction of the President."

This traditional distancing has been seen as especially important for the Justice Department, since it wields significant power in deciding who to investigate and prosecute.

Douglas Kmiec, who held senior positions in the Justice Department under presidents Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush, called Dershowitz’s comment "an overstatement of the proposition that law enforcement is an executive function. Of course it is, and in that sense it is under the general supervision of the president. But basic principles of due process necessarily preclude a president from interceding into the enforcement of the law against individual defendants."

So where is the line for obstructing justice? Perspectives like Dershowitz’s conflate proper and improper efforts to intervene, said James D. Robenalt, a Cleveland lawyer who runs a continuing legal education class on Watergate and its lessons.

"While a president can direct an investigation to start or cease, it cannot be for corrupt purposes," Robenalt said. "That would be obstruction."

This stems from a portion of U.S. law that says, "whoever corruptly obstructs, influences, or impedes any official proceeding, or attempts to do so, shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than 20 years, or both."

"The intent," Robenalt said, "is what matters."

Watergate is the best example. Prosecutors showed that President Richard Nixon ordered Attorney General Richard Kleindienst to end an antitrust investigation into ITT in return for the company’s $400,000 contribution to the Republican Party. That resulted in Kleindienst pleading guilty to lying to Congress about Nixon’s order to end the investigation, Nixon facing impeachment for his direction to the CIA to tell the FBI to "turn off" its investigation of the Watergate break-in, he said.

How useful are Dershowitz’s examples of other presidents?

Several experts told PolitiFact that Dershowitz’s three examples do not offer strong precedents for the argument that Trump’s actions involving Flynn were clearly legal.

Dershowitz told PolitiFact that he had these examples in mind for each president he named: when Thomas Jefferson told his attorney general to prosecute Aaron Burr for treason, the time Lincoln sought to punish Civil War-era disloyal northerners, and the time Franklin D. Roosevelt ordered a military tribunal for Nazi spies who had infiltrated the United States mainland.

Historians faulted the comparison with these three episodes, saying that Trump’s situation is fundamentally different and, at least in some ways, more problematic.

"Burr may have been a rival, but he went out west and illegally engaged in privateering and allegedly treason," said Jed Shugerman, a legal historian at Fordham Law School. "I don’t think anyone can say with a straight face that Jefferson was acting corruptly. He properly exercised his powers to stop an alleged mini-republic in the west."

Joe Wheelan, author of Jefferson's Vendetta: The Pursuit of Aaron Burr and the Judiciary, agreed: "It would be a great error to cite the Jefferson-Burr case as a precedent for Trump’s actions."

Meanwhile, the cases of Lincoln and Roosevelt stemmed from war, which sets them apart from the Trump example because of the commander in chief power under Article II.

In fact, the Nazi saboteur case is different in another way: The defendants didn’t have the same constitutional rights as Americans.

"They were treated as illegal enemy combatants in a time of war," said Michael Dobbs, author of Saboteurs: The Nazi Raid on America. "Their position is more analogous to post-9/11 terrorists sent to Guantanamo."

Meanwhile, historians added that these precedents are tainted.

David O. Stewart, author of American Emperor: Aaron Burr's Challenge to Jefferson's America, said that the prosecution, which led to an acquittal, was "bungled" and is "generally considered one of Jefferson’s larger missteps."

As for the saboteur case, Roosevelt acted in ways that, in retrospect, are seen by many as problematic. He had direct correspondence with Francis Biddle, the attorney general; he made clear that he thought the accused deserved the death penalty; and he had informal contacts with Felix Frankfurter, one of the Supreme Court justices that ended up hearing the case, Dobbs said.

The Nazi saboteur case would be "a terrible precedent" to use in justifying proper presidential behavior, said Louis Fisher, author of Nazi Saboteurs on Trial: A Military Tribunal and American Law.

That said, there’s one thing experts agree on: If Special Counsel Robert Mueller attempts to prove obstruction of justice, he has his work cut out for him.

"Anyone who speaks with utter confidence about the legality (of what Trump did) is probably stretching it, because all of this is relatively unprecedented," Shugerman said. "It boils down to proving corrupt intent. Anyone who says that’s easy has a case of hubris."

Our Sources

Alan Dershowitz, remarks on Fox & Friends, Dec. 4, 2017

Donald Trump, tweet, Dec. 4, 2017

Donald Trump, tweet, Dec. 2, 2017

Text of 18 U.S.C. 1512(c)(2)

Shugerblog, "Yes, Trump can be guilty of obstruction," Dec. 4, 2017

Email interview with Ric Simmons, law professor at Ohio State University, Dec. 4, 2017

Email interview with Joshua Dressler, emeritus law professor at Ohio State University, Dec. 4, 2017

Email interview with Stephen B. Presser, emeritus legal history professor at the Northwestern University School of Law, Dec. 4, 2017

Email interview with Kermit Roosevelt, law professor at the University of Pennsylvania, Dec. 4, 2017

Email interview with Carl Tobias, University of Richmond law professor, Dec. 4, 2017

Email interview with James D. Robenalt, Cleveland lawyer who runs a continuing legal education class on Watergate and its lessons, Dec. 4, 2017

Email interview with Ronald Rotunda, law professor at Chapman University, Dec. 4, 2017

Email interview with Joe Wheelan, author of Jefferson's Vendetta: The Pursuit of Aaron Burr and the Judiciary, Dec. 4, 2017

Email interview with David O. Stewart, author of American Emperor: Aaron Burr's Challenge to Jefferson's America, Dec. 4, 2017

Email interview with Michael Dobbs, author of Saboteurs: The Nazi Raid on America, Dec. 4, 2017

Email interview with Louis Fisher, author of Nazi Saboteurs on Trial: A Military Tribunal and American Law, Dec. 4, 2017

Interview with Jed Shugerman, legal historian at Fordham Law School, Dec. 4, 2017

Email interview with Douglas Kmiec, Pepperdine University law professor and former Justice Department official in the Reagan and George W. Bush administrations, Dec. 5, 2017

Email interview with Alan Dershowitz, emeritus law professor at Harvard, Dec. 4, 2017

PolitiFact Rating:

PolitiFact Rating: