Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

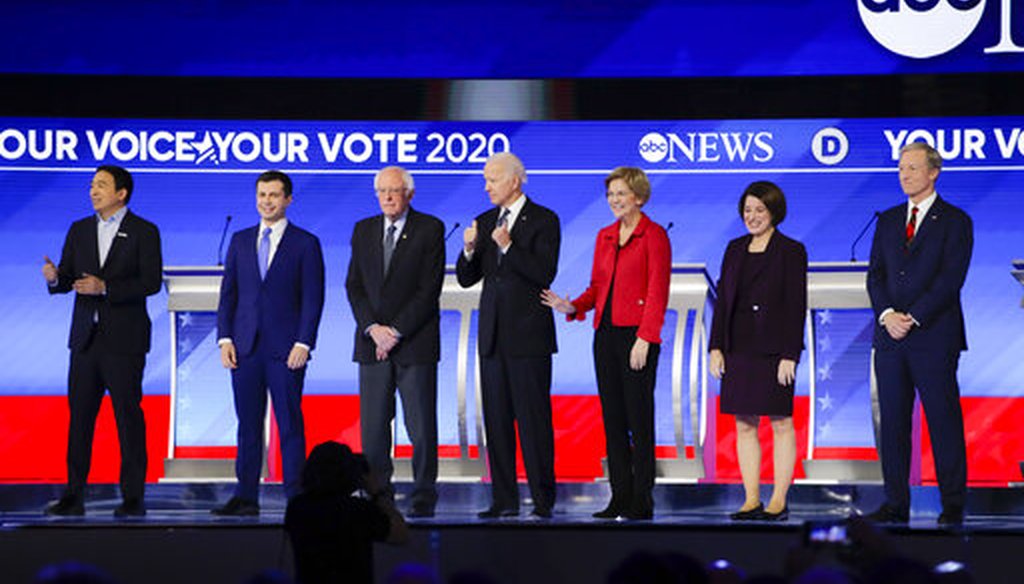

Democratic presidential candidates on stage Friday, Feb. 7, 2020, before the start of a primary debate hosted by ABC News, Apple News, and WMUR-TV at Saint Anselm College in Manchester, N.H. (AP/Charles Krupa)

If Your Time is short

- Democratic presidential candidates debated days before New Hampshire's Feb. 11 primary.

- Health care, foreign policy and President Donald Trump among top issues debated.

Just a few days before the New Hampshire primary, Democratic presidential candidates tried to convince voters why each of them has the best shot at unifying voters and defeating President Donald Trump at the polls in November.

Former South Bend, Ind., mayor Pete Buttigieg, a top finisher in the Iowa caucuses, told voters that now was not the time to fall back on the familiar. Sen. Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota and former Vice President Joe Biden shot back, arguing that experience is what’s needed to take on Trump.

On stage at Saint Anselm College in Manchester, N.H., were Biden, Buttigieg, businessmen Andrew Yang and Tom Steyer, and senators Klobuchar, Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders.

We fact-checked their claims on health care, foreign policy, taxes, and attacks on Trump.

Klobuchar: "You sent out a tweet just a few years ago you said henceforth, forthwith you are for Medicare for All for the ages."

and

Buttigieg: "The truth is I have been consistent throughout in my position on health care for every American."

Klobuchar and Buttigieg sparred over his record of support for Medicare for All, the single-payer health care bill that Bernie Sanders backs. Klobuchar noted that Buttigieg previously tweeted in favor of the bill and has since changed his position. Buttigieg said he has been consistent on supporting an approach that would bring health care to all Americans.

Klobuchar’s point — that Buttigieg has at least expressed support for the specific bill, and no longer does — is supported by evidence.

The tweet was posted on Feb. 18, 2018. Buttigieg wrote, "I, Pete Buttigieg, politician, do henceforth and forthwith declare, most affirmatively and indubitably, unto the ages, that I do favor Medicare for All, as I do favor any measure that would help get all Americans covered."

Since then, Buttigieg has narrowed his stance — backing "Medicare for all who want it," a plan he argues would also achieve universal coverage, by letting people opt into a public health plan, and offering more generous subsidies for those who purchase private insurance. (Proponents of single-payer are skeptical it would succeed.)

To be fair, even Buttigieg’s 2018 statement includes an important qualifier — he’s not tied to the plan. He favors Medicare for All, he says, as he does "any measure that would help get all Americans covered." If you agree that his current plan would also achieve universal health care, there’s an argument that he has been consistent.

— Shefali Luthra

Biden: Sanders’ Medicare for All plan "would cost more than the entire federal budget that we spend now."

This is not accurate. We contacted Biden’s campaign, who directed us to the 2018 federal budget — $4.1 trillion — compared to the estimated $32 trillion price tag of Sanders’ single-payer proposal. But there’s a problem: That latter number is an estimate of the cost for 10 years. So putting one year of the budget against a decade of health spending is comparing apples and oranges.

And converting one year’s budget to a decade-long forecast is an economically complex proposition — it’s not as simple as just multiplying by 10.

We also ran this claim by an independent expert, who crunched the $32 trillion estimate. Linda Blumberg, an institute fellow at the Urban Institute, told us Biden’s comparison is "an exaggeration" and "overstatement."

Certainly, she said, Medicare for All would be "a bigger increase to the federal budget than we’ve ever experienced" — more than a 70% increase, compared to the CBO’s 10-year budget estimate.

"This is an enormous increase, but it wouldn’t double" the budget, she said.

— Shefali Luthra

Warren: "36 million Americans last year couldn’t afford to fill a prescription, including those with insurance."

This is True. If anything, it falls a little short.

The data comes from a Commonwealth Fund estimate. Researchers found that in 2018, 37 million non-elderly Americans, about 1 in 5 people, skipped a prescription because they couldn’t afford it. Some of those people had coverage. Others were "underinsured." That means they had insurance, but it wasn’t enough to safeguard them from large medical bills.

Other data suggests it’s potentially even worse. A November poll from West Health and Gallup estimated that 58 million Americans experienced what they called "medication insecurity" in the past 12 months.

— Shefali Luthra

Warren: "How about we start with what a president can do — I love saying this — all by herself? On day one I will defend the Affordable Care Act and use march-in orders to reduce the costs of commonly used prescription drugs like insulin and HIV/AIDS drugs and EpiPens."

It is True that the president has these executive powers. But it’s likely it would be difficult.

Warren has in her "Medicare for All" transition plan a pledge that she would use two legal mechanisms to achieve this goal — "compulsory licensing" and march-in rights.

Compulsory licensing means the government will take over a patent if a drug’s prices are too high and create competition. There is precedent for this approach, it was done in the 1960s for cheap generic drugs, and in 2001 for Ciprofloxacin during the anthrax scare. Experts said this likely couldn’t be applied to all drugs but could work for insulin and EpiPens.

March-in rights are when the government "marches in" during a public health crisis because a drug isn’t available. But it only works for drugs in which the government holds all of the patents, such as Truvada, the HIV prevention drug. However, this mechanism has never been employed and it’s unclear whether high prescription drug prices would qualify as a public health concern. Officials at the National Institutes of Health would also have to approve this measure, and it would face significant backlash from the pharmaceutical industry.

— Victoria Knight

Sanders: "The health care industry makes $100 billion in profit."

Sanders’ math holds up — and is probably an underestimate.

The figure is derived by adding the "net revenues" for 10 pharmaceutical companies and 10 companies that work in health insurance. Multiple independent economists reviewed the methodology with, and affirmed that it’s sound. In fact, the total "net revenue" is actually around $100.96 billion.

The talking point doesn’t include health care’s biggest earners, though: hospitals and health systems. When you factor them in, the level of profit in our system will grow significantly larger.

— Shefali Luthra

Sanders: "30,000 Americans a year die waiting for health care because of the cost."

The way Sanders uses this number is problematic and oversimplifies the research. When we previously fact-checked this claim, we rated it Half True.

It appears that the number comes from Physicians for a National Health Program, which cited the Oregon Health Insurance Experiment, a study that assigned by lottery some participants to Medicaid and the others remained without insurance. A year into the experiment, researchers found that the death rate differed by 0.13 percentage points between those who were on Medicaid and those who were not — though this difference was not statistically significant. If you extrapolate this number to the number of Americans who are uninsured — about 27 million — then you do get close to a figure of about 30,000 people.

However, experts said that since the difference was not statistically significant it shouldn’t be extrapolated so broadly, and it’s possible that Sanders’ number is too high. Other research does show that there is a connection between being uninsured and higher likelihood of mortality. Thousands of Americans do die waiting for health care every year, but this number relies on imprecise math.

— Victoria Knight

Buttigieg: Said Donald Trump refused "to serve when it was his turn."

There is no proof that Trump orchestrated his medical deferment to avoid the draft, but questions remain. This reference to Trump’s past rests on partial evidence.

Buttigieg, who was a lieutenant in the Navy Reserve posted to Afghanistan, was referring to Trump’s Vietnam War era draft deferment. Between 1964 and mid 1968, Trump benefited from student deferments that exempted him from the military draft.

Aside from being a student, he had been judged 1-A, meaning available for service. When he completed his studies, he was once again classified as 1-A. Trump then saw a doctor, and a short time later his classification changed to 1-Y. It was based on a medical condition and meant he would only be drafted if there was a national emergency. Years later, Trump said it had to do with bone spurs in his heels. Trump reportedly was active in college sports, playing baseball, tennis and squash.

Trump failed to mention his medical deferment when he told ABC News on July 19, 2015, that he was never drafted because the draft lottery went into effect and his birthday came with a high number.

"If I would have gotten a low number, I would have been drafted. I would have proudly served," he said. "But I got a number, I think it was 356. That’s right at the very end. And they didn't get, I don’t believe, past even 300, so I was not chosen because of the fact that I had a very high lottery number."

— Jon Greenberg

Sanders: "I am very proud that today I have a D-minus voting record from the NRA."

We rated this Mostly True when Sanders claimed it during the 2016 Democratic primary contest. Sanders’ campaign back then told us that his D-minus NRA grade came during the 2012 election cycle, as shown in the NRA lobby group’s subscriber-only database. The NRA in 2016 corroborated Sanders’ low score.

The grade technically comes from the NRA’s political action committee, the NRA-Political Victory Fund. It has graded Sanders as far back as 1992, when he ran for his second term for Congress as an independent from Vermont. In the 1990s and early 2000s, Sanders got five straight Fs. The group gave him a D-plus in 2004 and a C-minus in 2006, his first bid for the Senate.

Sanders’ record on gun control has been scrutinized in the 2016 and 2020 election cycles. Biden claimed, accurately, that Sanders in the 1990s voted five times against the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act. Here’s an overview of Sanders’ record on gun control.

— Miriam Valverde

Yang: Says that Amazon "is literally paying zero in taxes."

That’s not the case for 2019. Amazon’s latest regulatory filing said it estimated it would pay $162 million in federal income tax for 2019.

Yang’s claim has more standing for 2017 and 2018. Amazon did not expect to pay federal income tax for those years, reporting a federal income tax bill of negative $137 million in 2017 and negative $129 million in 2018, according to its annual 10-K filings with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.

Amazon’s tax returns are private, but experts have told us that the best and closest source of information on Amazon’s tax liabilities can be inferred from the SEC filings.

— Miriam Valverde

Buttigieg: Says Trump withdrew from "the Iran nuclear deal that his own administration certified was working."

This is accurate. The 2015 multinational agreement that rolled back Iran’s nuclear program, lifted sanctions, and opened the country to international inspections required regular certification of compliance. The formal name of the agreement is the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, or JCPOA.

In a State Department briefing March 21, 2018, director of Policy Planning Brian Hook said Iran was living up the deal. Under the agreement, Iran gave up 97% of its stockpile of enriched uranium. It also lost 14,000 of its 20,000 centrifuges, the machines used to enrich uranium, and it agreed to only enrich uranium to a level unsuitable for weapons for 15 years. It also had to dismantle its plutonium reactor.

"They are in technical compliance with their commitments under the JCPOA," Hook said.

On May 8, 2018, Trump announced that the United States would re-impose economic sanctions on Iran and Washington would no longer hold to the agreement.

— Jon Greenberg

Our Sources

Listed in the story.