Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

President Donald Trump speaks before pardoning the national Thanksgiving turkey on Nov. 24, 2020, as first lady Melania Trump watches. (AP)

If Your Time is short

• The Constitution doesn’t explicitly bar presidents from pardoning themselves. While legal arguments can be made against it, no one really knows if a self-pardon would be upheld by the courts.

• A more legally secure path would be for a president to step down and have his successor pardon him. But it’s possible that the pardoner could face consequences.

• A presidential pardon could address crimes committed but not yet charged. However, they could not apply to crimes committed in the future.

Can President Donald Trump wield the power of the pardon to protect himself? This is a question readers have asked us, so we asked legal scholars about a range of scenarios.

Trump himself has asserted that doing so would be legal, although as he raised the possibility, he added that he wouldn’t need to, because he believed he had no legal worries.

"As has been stated by numerous legal scholars, I have the absolute right to PARDON myself, but why would I do that when I have done nothing wrong?" Trump tweeted on June 24, 2018.

Rudy Giuliani, a legal adviser to Trump, also pointed to the possible use of a self-pardon in 2018. Giuliani said Trump "probably does" have the power to pardon himself, though he said Trump had no intention of doing so.

Sign up for PolitiFact texts

We must emphasize here that there is no sign that any federal criminal cases have been opened against the outgoing president. It’s also far from certain that the incoming administration of Joe Biden would pursue any cases against the candidate he defeated.

But could Trump pardon himself if we wanted to? It’s not as clear cut as Trump said.

First, let’s review some basics. As we’ve noted, there aren’t many limits on a president’s pardon power.

Article II, Section 2, of the Constitution says the president "shall have the Power to grant Reprieves and Pardons for offenses against the United States, except in Cases of Impeachment."

The power of the pardon "is considered one of the least limited powers of the executive," said James Robenalt, a lawyer at the firm Thompson Hine and an expert on Watergate.

Robenalt said the authority can be traced back to the power of English kings to pardon. In Federalist Paper No. 74, Alexander Hamilton wrote, "Humanity and good policy conspire to dictate, that the benign prerogative of pardoning should be as little as possible fettered or embarrassed."

Legal experts also agree that one of the few requirements is that a crime needs to have been committed already for a pardon to be applicable.

"No ‘future crimes’ qualify, although the president can pardon as soon as the offense happens, and he does not need to wait for a formal legal process to be started against the accused," said Jeffrey Crouch, an assistant professor of American politics at American University who specializes in studying pardons.

This interpretation would probably also rule out a pardon for a crime that is ongoing at the time of the pardon, said Frank O. Bowman III, a University of Missouri law professor and author of a recent paper on presidential pardon power.

Meanwhile, the phrase "offenses against the United States" is generally meant to address federal criminal cases and to rule out state-level cases and civil cases. This could become a significant factor for Trump, since both New York state Attorney General Letitia James and Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance are investigating issues related to the Trump family and its real estate business.

James is investigating whether Trump and his companies improperly inflated the value of four properties, while Vance has been locked in a battle over Trump’s tax returns that, according to Vance’s court filings, could inform a broader fraud investigation of Trump.

A presidential pardon would also affect only criminal liability, not civil liability, Bowman said, and it would not preempt investigations launched by Congress.

Even legal experts who argue that a president shouldn’t be able to pardon himself tend to agree that no one really knows for sure.

"There is no consensus among scholars on whether a president may pardon himself," said Michael Gerhardt, a law professor at the University of North Carolina.

Perhaps the strongest argument that a self-pardon would be allowed is that the Constitution doesn’t explicitly prohibit it.

However, there are several circumstantial arguments that, collectively, make a strong case that a self-pardon isn’t allowede, experts said.

For starters, the Constitution’s pardon clause uses the verb "grant," which ordinarily means giving to someone else, said Harold H. Bruff, an emeritus University of Colorado law professor. Going back to its English monarchical origins, a pardon has long been conceived as an act of mercy. Neither of these suggest something that can be done to oneself.

In addition, Bruff said that when the Constitution was being written, "a background value everywhere in the air was that no one should be a judge in their own cause." This notion, sometimes referred to in Latin as "nemo judex in causa sua," is a longstanding common-law principle, he said.

"People cannot prosecute, judge, or sit on juries in their own cases. Like a judge who would have to submit to the authority of another judge if he were being prosecuted, a president must seek a pardon from his successor," wrote Brian Kalt, a Michigan State University law professor who has studied pardons.

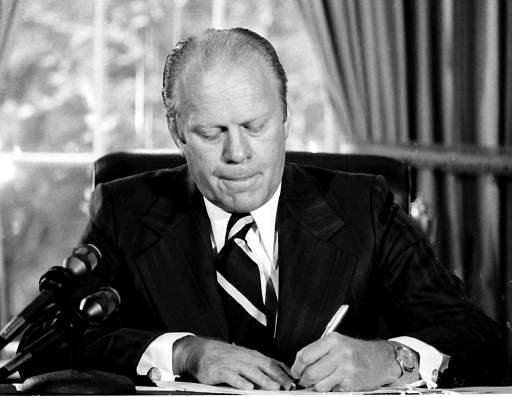

That is what happened with President Richard Nixon. It was his successor, Gerald Ford, who ultimately gave Nixon a wide-ranging pardon for Watergate-related crimes.

Experts also refer to James Madison, who wrote in Federalist Paper #10 that "no man is allowed to be a judge in his own cause, because his interest would certainly bias his judgment, and, not improbably, corrupt his integrity."

However, Robenalt noted that Madison was not specifically referring to the pardon power in this instance. This, Robenalt said, makes the law "unsettled. It is not as easy to answer as it seems. There are pro and con points to be made."

Ultimately, no one knows for sure how any of this could play out until the Supreme Court rules. "You never know until you have the temerity to try," said Daniel Kobil, a law professor at Capital University. "Even Richard Nixon didn’t have the temerity to try it."

In the real world, Pence might not be amenable to this sort of bargain. But experts agree that such a pardon would probably be valid if he did.

A pardon of this sort could play out in a couple of ways. The president could simply resign, as late as a few minutes before Joe Biden was due to be sworn in, and allow the vice president to become president for that brief period of time. If the pardon papers were already drawn up, Pence could quickly sign them, and they would become valid.

Alternately, the 25th Amendment allows a president to temporarily hand over the powers of his office by transmitting a message to Congress. Once that happens, the full powers of the presidency fall to the vice president, who becomes "acting president." Once the acting president issues the pardon, the president could retake his office by sending another message to Congress.

"Purely as a matter of constitutional interpretation," Bowman wrote, both of these options "are perfectly plausible." A pardon could even be written to cover Trump’s family members.

One obstacle, Bowman wrote, is whether Trump would be willing to cede his presidential powers, even briefly. And Pence would risk public criticism for taking part in this activity. "At the time of the constitutional conventions, a delegate from North Carolina said that the only limit on the president's power was his fear of ‘the damnation of his fame to all future ages,’" said Margaret Love, a Justice Department pardon attorney from 1990 to 1997.

This could harm any future political ambitions Pence harbors, as well as risk embroiling him in congressional investigations. Pence could even be risking legal consequences for himself, experts say. "A bargain like that could be considered corrupt, and possibly criminal," said Brian Kalt, professor of law at Michigan State University.

Whatever consequences Pence might face for offering the pardon, there is broad agreement that the pardon for Trump in this scenario would hold.

Experts say the answer is quite clear: Yes. While pardons are normally granted after the legal process has run its course, they can be granted for crimes that have occurred, but which haven’t been charged yet.

In 1866, the Supreme Court ruled in the case Ex Parte Garland that presidential pardon power "extends to every offence known to the law, and may be exercised at any time after its commission, either before legal proceedings are taken, or during their pendency, or after conviction and judgment." This view was bolstered by the 1925 ruling in Ex Parte Grossman.

In fact, there’s a historical precedent: This is what happened with Ford’s pardon of Nixon, which granted "a full, free, and absolute pardon unto Richard Nixon for all offenses against the United States which he, Richard Nixon, has committed or may have committed or taken part in during the period from January 20, 1969 through August 9, 1974."

In his memoir, Watergate special prosecutor Leon Jaworski said he had considered challenging Ford’s pardon, but he decided against it, Love said.

Presidential candidate Jimmy Carter speaks to members of the American Legion at their national convention in 1976. He called for a blanket pardon for Vietnam draft resisters, and hundreds of delegates hooted and shouted "No." (AP)

A few earlier examples exist as well, Bowman said. They include President Andrew Johnson’s pardoning of former Confederates and President Jimmy Carter’s amnesty for Vietnam-era draft evaders. Many recipients in both cases had not been charged with any crimes.

It should be noted that Ford’s pardon of Nixon was unusually broad. While such a broad pardon for Trump would likely be upheld in court, Bowman said, the broader the sweep of the pardon, the more fodder for opponents in seeking to overturn it in court.

"When Carter did a pardon for draft evaders, he identified what they were convicted of and pardoned them for that," Bowman said. "Other than Nixon, no one has ever been given a complete pass. If it had come out later that Nixon had been taking bribes or ordering secret murders of foreign ambassadors, the pardon would have covered it all. So it was a pretty bold move. I think that’s probably constitutional, but it’s sufficiently unprecedented in American and British practice that you can imagine someone challenging that."

Our Sources

PolitiFact, "Can the president pardon himself? 4 questions about the presidential pardon," July 21, 2017

Constitution of the United States, Article II, Section II, accessed July 21, 2017

James Madison, "The Federalist Papers: No. 10," Nov. 23, 1787

Alexander Hamilton, "The Federalist Papers: No. 74," March 25, 1788

Ex parte Garland, 71 U.S. 333 (1866)

Ex Parte Grossman, 267 U.S. 87 (1925)

Text of Ford’s pardon of Nixon, Sept. 8, 1974

Donald Trump, tweet, June 4, 2018

CNN, "Trump: 'I have the absolute right to pardon myself,' June 4, 2018

Frank O. Bowman III, "Presidential Pardons and the Problem of Impunity" (N.Y.U. Journal of Legislation and Public Policy), Nov. 16, 2020

Brian C. Kalt, "Pardon Me?: The Constitutional Case Against Presidential Self-Pardons," Yale Law Journal, 1996

Adrian Vermeule, "Contra Nemo Iudex in Sua Causa: The Limits of Impartiality" (Yale Law Journal), November 2012

Michael J. Conklin, "Can a President Pardon Himself? Law School Faculty Consensus" (Northeastern University Law Review), Winter 2020

Washington Post, "Trump team seeks to control, block Mueller’s Russia investigation," July 21, 2017

Washington Post, "Can Trump pardon anyone? Himself? Can he fire Mueller? Your questions, answered," July 21, 2017

Washington Post, "Trump’s post-presidency will be cluttered with potentially serious legal battles," Nov. 22, 2020

Democrat and Chronicle, "Donald Trump's taxes already at issue in at least two NY investigations," Sept. 28, 2020

New York Times, "Trump Tax Write-Offs Are Ensnared in 2 New York Fraud Investigations," Nov. 19, 2020

Politico, "Carter pardons draft dodgers Jan. 21, 1977," Jan. 21, 2008

NPR, "Amnesty: A Brief Primer," July 2, 2007

CNN, "Can President Trump pardon himself?" July 21, 2017

Brian Kalt, "Can Trump Pardon Himself?" (Foreign Policy), May 19, 2017

Steve Vladeck, "Five Questions about the Scope and Limits of the President’s Pardon Power," July 21, 2017

Politico, "President Carter pardons draft dodgers, Jan. 21, 1977," Jan 21, 2018

PolitiFact, "Obstruction of justice, presidential immunity, impeachment: What you need to know," May 17, 2017

Interview with Akhil Amar, professor of law and political science at Yale University, July 21, 2017

Email interview with Kermit Roosevelt, University of Pennsylvania law professor, July 21, 2017

Email interview with Erwin Chemerinsky, dean of the University of California law school, July 21, 2017

Email interview with Ronald D. Rotunda, law professor at Chapman University, July 21, 2017

Email interview with Stephen I. Vladeck, law professor at the University of Texas, July 21, 2017

Interview with Harold H. Bruff, emeritus University of Colorado law professor, July 21, 2017

Email interview with Jeffrey Crouch, assistant professor of American politics at American University, Nov. 23 2020

Email interview with Margaret Love, former Department of Justice pardon attorney from 1990 to 1997, Nov. 23 2020

Email interview with Brian Kalt, professor of law at Michigan State University, Nov. 23 2020

Email interview with Daniel Kobil, law professor at Capital University, Nov. 23 2020

Email interview with Michael Gerhardt, professor at UNC School of Law, Nov. 23 2020

Email interview with James Robenalt, lawyer at the firm Thompson Hine, Nov. 23 2020

Interview with Frank O. Bowman III, University of Missouri law professor, Nov. 23, 2020