Get PolitiFact in your inbox.

If Your Time is short

-

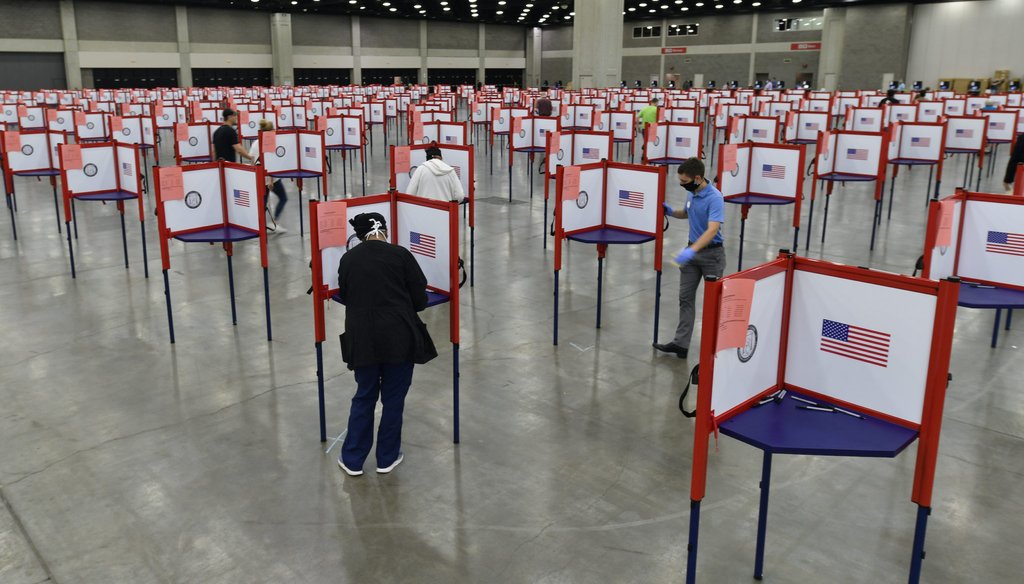

This year, Election Night could be chaotic. In addition to coping with an unprecedented number of mail ballots, the coronavirus pandemic requires election officials to provide clean, socially distanced, in-person voting operations and grapple with a likely shortage of election workers.

-

Journalists must report on the election results with special care so citizens understand that the ballots in some places could take days to count. With widening partisan preferences in the methods of casting and tallying ballots, journalists may have to counter misinformation about voting patterns and who is on track to win.

-

National media outlets understand these dynamics and are adapting their approaches and their journalism to respond, according to discussions with 17 political experts who participated in a two-day, four-panel discussion convened by the Poynter Institute.

2020 has been quite a year of history and news: a presidential impeachment, the coronavirus pandemic, racial justice protests, economic hardship, rampaging wildfires and hurricanes. Now, as the year enters its final months, another potentially seismic moment: a potentially chaotic Election Night that might turn into an Election Week.

Some states (though not all) have simplified the process of mail voting, often by eliminating the need for an "excuse" to vote by mail. A few states are going so far as to send ballots to every active registered voter in 2020, joining five states that have conducted elections by mail for years.

In addition to coping with unprecedented numbers of mail ballots, election officials will have to take exceptional steps to ensure the health and safety of in-person voters and election workers because of the risk of coronavirus.

The other factors that complicate the 2020 election include heightened political polarization and a deluge of misinformation on social media. Elections experts and partisans of all stripes share a common anxiety: Will this multitude of factors jeopardize the functioning of democracy?

The media’s role in declaring a presidential winner is almost unique. "There isn’t a ceremony that happens on Election Night that crowns someone the presidential victor," said ABC News political director Rick Klein. "It happens through the media, through our coverage."

National media outlets are taking their role especially seriously this year, according to discussions with 17 political experts who participated in a two-day, four-panel discussion sponsored by the Poynter Institute. The discussion (view an archived video), addressed the finer points of how election officials will tabulate the crush of mail ballots, how the television networks are changing their coverage plans, and how reporters can debunk misinformation.

Below is a summary of the five hours of discussion in the Poynter webinars, ending with 12 practical recommendations for journalists who will be covering the election.

What to expect after the polls close

Here are some of the things that will be different on Election Night 2020:

Counting ballots may take longer than previous years. Ballots cast by mail require extra steps to verify a voter’s identity, including comparing signatures to prevent voter voter fraud or double counting. This takes time. In addition, some states allow ballots postmarked prior to Election Day to be counted even if they arrive in the mail several days after the polls close. So it may take days to call the winner of the presidential race.

States will have divergent rules on when they can start counting ballots. In some states, election workers will be able to get ballots ready for counting several days before the election, doing things like checking the voter’s identity to make sure they are properly registered. But in other states, officials can't touch ballots until Election Day after the polls close.

These differences will affect how fast results can be passed along to the public.

Partisan patterns may be revealed when ballots are counted. Not only is mail balloting expected to be used more heavily this fall due to the pandemic, but surveys suggest a split among voters that stems from President Donald Trump’s oft-expressed skepticism about mail voting. Put simply, more Biden voters say they will vote by mail, and more Trump voters say they will vote on Election Day.

If this pattern holds for the rest of the election season, then returns that are counted on election night returns might skew Republican, with mail ballots that arrive and are counted later skewing Democratic. Some observers have been calling this the "blue shift." In some cases, this pattern will be reinforced by rural, more Republican areas having their ballots tallied first, while urban, more Democratic areas with heavier ballot loads are counted later.

"We want our readers to understand that it's very possible that Trump may lead in battleground states at 10 p.m. on Election Night, but that it doesn’t mean he’s going to win all of them," said Geoffrey Skelley, elections analyst with FiveThirtyEight.com. "We may see some very large swings in the vote count, and we need to relay that to readers now."

Leading news organizations are preparing new ways to estimate how much of the vote remains uncounted. For decades, media organizations showed the "percentage of precincts reporting." But in an election conducted heavily by mail, this metric has become meaningless, even misleading: The percentage of precincts counted may be close to 100% yet not take into account a large number of untallied mail ballots.

The TV networks have transitioned to a metric called "percentage of expected vote," which is produced by calculations of how many mail ballots were requested and returned, and by historical patterns in state and county turnout.

Top journalists say they are tamping down the push to be the first to call a winner. "There is not as much pressure this year to break the land speed record," said Amy Walter, national editor of the Cook Political Report and an elections analyst for the PBS NewsHour. "Being accurate is more important than being first. You’re going to see similarity across the networks. At some point the numbers are going to be the numbers."

Elections analysts say the threshold for calling races will remain as stringent as they’ve been in the past. "We want to be 99.5% sure before we project a race," said John Lapinski, director of the NBC News elections unit. He added that the lengthy primary season has given decision desks a chance to work out the kinks.

So when will the outcome of the presidential race be called? The consensus among experts is a couple of days. "I think by the weekend, we will know, barring legal challenges," Walter said.

Social media and extreme partisanship will stoke misinformation. Experts worry that candidates and other partisans will take to social media to cite partial results and declare a premature victory. It will be up to journalists to portray the situation accurately. Social media will also be a source of allegations about voter suppression and fraud in counting.

RELATED: A pre-election guide to reporting on the weirdest election ‘night’ ever

Recommendations for news professionals: Before Election Night

The Poynter panelists had a variety of recommendations for journalists on election night. Here are some of their tips.

1. Figure out a coronavirus safety plan for your newsroom.

All the preparation in the world won’t matter if you’re too sick to work. Reporters will be out on the street talking to voters, and at polling places and election supervisor headquarters. Develop plans and provide relevant equipment, such as masks, to keep your staff safe.

2. Familiarize yourself with the voting rules, and prioritize "news you can use."

Do the legwork now. Journalists owe it to their readers and viewers to fully understand the voting process and local rules by the time voting starts. Every state has a different system, and within states, some localities have their own rules. Become the experts. And be prepared to answer audience questions as long as the polls are open. FiveThirtyEight offers one comprehensive source of information, as does the National Conference of State Legislatures.

Even the terms used to describe the election process can get confusing, so share the proper terms with your audience. For instance, "‘process a ballot" often refers to a machine removing the outer envelope and flattening the ballot, while "tabulating a ballot" means actually counting it. CBS News has a useful dictionary of election terms, but check with election officials to see if they match up with the state you’re covering.

Start making contacts among election-law experts, including those from both major parties. You will need these sources if races are contested in your state. Have a plan to reach out to them on election night or after.

3. Use the early-voting period as a dry run to identify problematic polling sites early.

Make contact with your local election officials as soon as possible, before a busy Election Night. Learn what officials expect about the timing of when mailed ballots will arrive, when they’ll be ready for counting, when the counting formally begins, and how the early and in-person voting will take place. Ask about their contingency plans in case things go awry, and find out what steps they are taking to keep voters and poll workers safe from COVID-19.

"We have a three-week early voting period in Georgia, and will be covering that extensively," said Greg Bluestein, a political reporter for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. "If there are issues in polling places during early voting, you can bet those will be the places that will experience issues on election day."

All in all, "this will be the most difficult election we’ve faced in our lifetimes," Lapinski of NBC News said. "But the good news is that when we look at the people in election administration … these are good people and really smart."

4. Set expectations for your audience carefully, and often.

It’s never too early to remind voters that it could take several days to determine a winner of the presidential race. Tell viewers and readers not to expect to turn your TV on at 11 p.m. knowing who will be the next president, Walter said.

Repeating this message will take discipline, said Caitlin Conant, political director for CBS News. "I’m not a patient person myself," she said. "But we have to lay the groundwork for certain scenarios. At the core of what we do is public service."

RELATED: The challenges of the 2020 election — What we’re reading

Recommendations for news professionals: On Election Night

5. Remember that not every state will matter equally in the presidential race.

Almost three-quarters of the states are securely in the column of one presidential candidate or the other. The remaining will be competitive this year, but only a dozen will receive the most attention from the campaigns, because they are expected to prove decisive in electing the winner.

The most commonly cited states in this category are Arizona, Florida, Michigan, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, or Wisconsin. So even if there are problems with ballot counting in some states, in most cases they won’t prove decisive.

6. Report what ballots are still untallied, and make clear that slowly counted votes are not fraudulent votes.

Don’t make assumptions on your own about the data. Trust the estimates of the major vote tabulators for the media, including Edison, AP, and Decision Desk HQ.

Caution your audience that there could be significant swings in the count and that it’s not a sign of something going wrong — it’s just the process methodically playing out. "The country shouldn’t have a collective freakout if counting continues without a winner," said Sam Feist, CNN’s Washington bureau chief.

7. Exit polls can be useful, but don’t make calls of who won based on what they find.

Exit polls — the surveys taken of voters leaving polling places, augmented by phone surveys of those who cast their ballots by mail — provide useful snapshots of the mindset of the electorate, but their usefulness for calling races is limited. It’s a misconception that exit polls are used to call close races.

"None of us are going to make a call in a competitive race based on exit polls, period," Feist said.

8. It’s OK to say when you don’t know the answer yet.

When there haven’t been enough votes counted to be sure who’s ahead, or when the margins are too close to make a call, don’t rush. It’s more accurate and responsible to say there’s "no clear leader," or that a race is "too close to call," than to focus on who is leading with a small margin.

9. Consult both parties when covering issues of voter fraud

Every election cycle brings claims of voter fraud, but with the expected significant uptick of Americans voting by mail this year, it’s important to be hyper vigilant about how you cover the issue and who you consult.

Speak with experts from both parties and those without a party affiliation. Also consider speaking with officials from states that already use mail for most of their voting, including Colorado, Hawaii, Oregon, Utah, and Washington.

10. Counter misinformation when you see it.

Some claims can be investigated quickly, but complex claims may be time-consuming, especially if they haven’t previously been vetted in the media and if information is hard to get.

When reporting on misinformation, debunk or clarify the claim as early as possible in the story, and make sure not to give a misleading impression with headlines and in social media. Online tools such as Crowdtangle can help you find out what’s gaining traction online and reverse-image search tools like Rev Eye can help you verify and track down viral images. Google’s Fact-check Explorer can lead you to fact-checking work by other journalists.

When confronted with mail-voting claims, consult the National Vote at Home Institute, an organization that advocates for voting by mail.

11. Emphasize the local view.

The big advantage that local media outlets have over national ones is that they already have journalists on the ground in the states. If a dispute arises in a specific state, reporters in local newsrooms are often best positioned to sort out the facts.

"Exit polls can get us to key themes and trends, but you have to layer this with on-the-ground reporting" in the states, Conant said. "Local reporters are well-positioned to ‘source up’ with local voters and officials. Take advantage of your strengths."

12. Be as transparent as possible and consult diverse sources.

Explain exactly what you are reporting and how you came to know it. Respond to reader questions, explain how you get to the conclusions that you draw, and show readers where you’re getting your information by linking to sources in the online version of your report. Be sure to consult both parties and look for independent experts with a track record of authority.

RELATED: Register for the webinar, "The Weirdest Election ‘Night’ Ever: Practical tools for sound election coverage."

Dealing with the unexpected

Even with all their advance preparation, what do the experts worry most about? Skelley of FiveThirtyEight said he worries that Americans might not absorb the need to be patient and will trust misinformation rather than credible reporting.

ABC’s Klein worries about the possibility of a hack of election infrastructure in a key state. "There are lots of failsafes to assure against that, but we can only do what we can based on the the data that’s there," he said. "That would be a crisis to me."

Feist of CNN said he worries that the election comes down to one state, and that it’s close enough to prompt a recount, which in turn triggers a fierce legal battle. That’s what happened 20 years ago in Florida. The 2000 election took 31 days and a ruling from the U.S. Supreme Court to decide it. Other panelists said they worry about voting misinformation or incompetence on Election Day.

For example, a person or group with nefarious motives may try to deter voters by falsely claiming that there are long lines at a particular polling place. Someone may try to scare people away from voting by showing up at a location, coughing on people, and claiming that they have the coronavirus.

Sometimes, problems will result from something as simple as disorganization. Bluestein covered Georgia's troubled primary election day in June. He said he interviewed people who had waited for five hours and still hadn’t voted by the time he left. One of the problems was that local officials and voters weren’t familiar with new equipment, and it led to major delays. "If you see lawn chairs as an accessory to voting, you know there’s a problem," Bluestein said.

All of this said, several panelists urged against assuming a worst-case outcome for 2020. A clear presidential winner and an orderly process is entirely possible. Let’s face it, the debate about the election process has been underway for months, so it’s possible local officials -- and voters -- are ready. News operations like ABC News have always put together a significant operation to make calls, Klein said, but this year, "from our on-air anchors to production assistants, we have to be open to a lot of different scenarios.

So whether it’s orderly, or whether it proves to be the weirdest election night ever, it is certain to be this: historic.

The Poynter Institute would like to thank the following journalists for participating in the discussions that led to the creation of this report:

Molly Beck, reporter covering state government and politics for the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

Greg Bluestein, political reporter for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution

Caitlin Conant, political director for CBS News

Eric Deggans, TV critic for NPR

Sam Feist, CNN’s Washington bureau chief and senior vice president

Rick Klein, political director for ABC News

John Lapinski, director of the NBC News elections unit

Joe Lenski, co-founder and executive vice president of Edison Research

Karen Mahabir, chief of fact-checking and misinformation coverage at the Associated Press.

Patricia Mazzei, Miami bureau chief for the New York Times and previously political writer for the Miami Herald

Drew McCoy, president of Decision Desk HQ

Julie Pace, Washington bureau chief of the Associated Press

Linda Qiu, fact-checking reporter with The New York Times

Amy Sherman, staff writer with PolitiFact

Geoffrey Skelley, elections analyst with FiveThirtyEight.com

Andy Specht, PolitiFact reporter at WRAL-TV in Raleigh, N.C.

Ashley Tally, manager of the enterprise team at WRAL-TV in Raleigh, N.C.

Amy Walter, national editor of the Cook Political Report, host of WNYC's Politics with Amy Walter on the Takeaway, and contributor to the PBS NewsHour

Our Sources

Conversations with panelists listed above