With Democrats Raphael Warnock and Jon Ossoff winning Senate seats in Georgia’s pivotal runoff elections, the U.S. Senate is now poised to become a 50-50 chamber.

What does this mean for how the Senate will operate once the two Democrats’ victories are certified? Experts say there is no written roadmap that Senate leaders must follow. However, there are historical precedents that the two parties’ leaders will likely use.

What is the significance of the vice president’s vote?

The vice president has the power to break tie votes, in his or her capacity as president of the Senate. According to Article I, Section 2 of the Constitution, "The Vice President of the United States shall be President of the Senate, but shall have no Vote, unless they be equally divided."

So, once she is sworn in as vice president, Kamala Harris may want to be on hand if a tie looks likely on a particular Senate vote.

Ties on votes can happen even when the Senate isn’t evenly split on party lines. (Note that two independents, Maine’s Angus King and Vermont’s Bernie Sanders, caucus with the 48 Democrats.) Vice President Mike Pence, for example, has cast many tie-breaking votes, even though Republicans controlled the Senate outright.

Sign up for PolitiFact texts

So will Harris function like a 101st senator?

Not really. She may have to hang around the Capitol more than she'd like when upcoming votes look close. But all vice presidents need to do that to some extent, especially when the majority’s margin is narrow.

The real significance of the vice president’s vote in an evenly split Senate comes in the opening days of the new Congress, as the Senate is organizing its operating rules. It’s Harris’ vote that effectively gives Democrats a claim to the majority, and that’s important because the rules of the Senate have historically given the leader of the majority broad powers to set the chamber’s schedule and legislative agenda.

Has an even split happened before?

There are three prior periods when the Senate was evenly split between the parties.

The first, in 1881, was known as the Great Senate Deadlock. While there was turmoil, "it never provided much of a precedent," said Washington University political scientist Steven Smith, because it was broken by a Democrat who voted with the Republicans to organize the Senate.

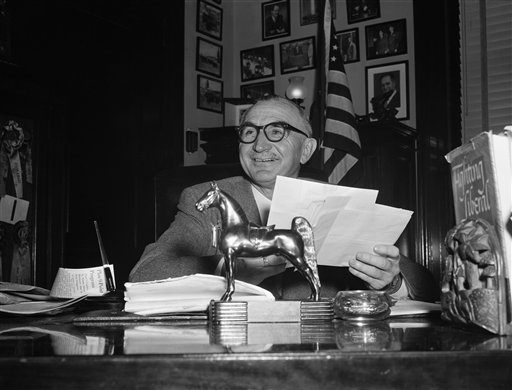

The second came in 1953, when Sen. Robert Taft, R-Ohio, died. The tie was resolved when the chamber’s one independent, Wayne Morse of Oregon, agreed to side with the Republicans on Senate organization.

The third came after the 2000 elections. The two parties’ leaders, Republican Trent Lott of Mississippi and Democrat Tom Daschle of South Dakota, forged a power-sharing agreement that lasted for about five months, until Sen. Jim Jeffords, R-Vt., became an independent and shifted to caucus with the Democrats. At that point, the Democrats were able to take the clear majority.

Sen. Wayne Morse with a batch of congratulatory telegrams after switching parties in 1954. (AP)

What was included in the 2001 power-sharing agreement?

Here are some of the key elements of the negotiations between the party leaders, according to the Congressional Research Service:

- Both party leaders would "seek to attain an equal balance of the interests of the two parties" in scheduling and considering Senate legislative and executive business;

- The leaders said they would not "fill the amendment tree," a tactic to block amendments on controversial issues.

- Committees would have equal numbers of Republicans and Democrats, but would be chaired by Republicans, and the parties would receive equal office space and budgets;

- Members of either party could serve as presiding officers of the Senate, rather than just senators of the majority party.

The power-sharing agreement, CRS wrote, "was an experiment. It differed from many established practices of the Senate. The agreement was not comprehensive, and new issues came before the Senate that had to be resolved by informal agreements, unanimous consent negotiations, or other means. The success of any Senate organizational settlement depends in part upon its adaptability and that of its members to changing circumstances."

Do the parties have to negotiate on the rules?

No. With Harris’ vote, Democrats could threaten to ram through a Democratic-written organizational plan that severely disadvantages the Republicans.

But Democrats may prefer negotiation to a solely Democratic plan because they may not be able to keep their own caucus in line to enact that option. There’s a long history of bipartisan "gangs" of institutional-minded senators who sought to play a role in shaping how the chamber’s rules are formed, and those senators would not support a Democratic-only plan.

"Before there can be a vote No. 51, there must be votes 50, 49 and 48," said Richard Cohen, chief author of the Almanac of American Politics and a longtime congressional correspondent. "Democratic senators who might have reservations about supporting the most liberal proposals, such as Sens. Joe Manchin of West Virginia and Kyrsten Sinema and Mark Kelly of Arizona, won’t want to be taken for granted by others in the Democratic conference."

How well did the 2001 agreement function?

Most accounts suggest the agreement worked pretty well, thanks to the good working relationship between Lott and Daschle. (The pair later co-authored a book, "Crisis Point: Why We Must, and How We Can, Overcome Our Broken Politics in Washington and Across America.")

Vice President Dick Cheney broke two ties on votes, both on amendments to a budget resolution. On three other occasions, the tie vote resulted in the defeat of the proposal, which was what Senate Republicans and the White House wanted anyway, Cohen said.

Notably, the two chief bills considered by the Senate in the first half of 2001 "were not party-line proposals," Cohen said. One was the McCain-Feingold campaign-finance bill, on which each party had extensive internal rifts. The other was one of President George W. Bush’s chief legislative priorities, the No Child Left Behind education-reform bill. From the start, Bush had pursued a bipartisan approach on the bill.

The 2001 agreement, and later side agreements made by Lott and Daschle, will have no official impact, but experts agree that they could serve as a template for potential negotiations between Chuck Schumer, the Democratic leader, and Mitch McConnell, the Republican leader.

The U.S. Senate chamber

Would there be a "majority leader" and a "minority leader"?

They may or may not use those terms in all situations. Sometimes, even in non-tied chambers, they are referred to as the Democratic leader and the Republican leader. But experts assume Schumer would function as the majority leader and McConnell as the minority leader, regardless of what title is used in the moment.

The limits of their powers, however, remain to be determined by whatever rules package they eventually enact.

"As for controlling the agenda, the Democrats will ensure they have standard majority party power, because in essence, they do," said Josh Ryan, a Utah State University political scientist. "I don't think there will be much agenda control given to the GOP. Agenda control is the raison d'etre for the majority party and its leader, so they won't give this up at all."

Is it realistic to think that Schumer and McConnell will end up striking an agreement as Lott and Daschle did?

It will be tougher, given the increasing polarization of politics generally and the Senate specifically.

"The Lott-Daschle agreement may be difficult to replicate," Smith said. "Lott struggled to get his ‘majority’ party to agree to the terms he negotiated after the 2000 elections. With so many uncompromising members of his party conference, McConnell will find it even more difficult."

Stewart Verdery, who worked for then-Sen. Don Nickles, R-Okla. said that he expects McConnell to argue that the 2001 precedent is fair and appropriate.

"At the moment, I give them only a 60% chance of agreeing to a bipartisan power-sharing plan," Smith said.

An early sign of how things are going will be "how quickly the parties agree on the power sharing agreement and how much the Republicans get from the agreement," Ryan said. "Will it reflect what happened (with Lott and Daschle), or will the Democrats push it a little farther?"

Will the chamber be referred to as the "Democratic Senate" or the "tied Senate"?

This is one point where experts aren’t sure.

In 2001, the media tended to use the term "tied Senate." In party control, Smith said, "the Senate is tied. The vice president is not a member of the Senate."

However, John Fortier, a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, said he expects that "most people will still refer to it informally as a Democratic Senate, as they will have the majority with the vice president’s vote."

Ryan splits the difference. "I would refer to it as a tied Senate with a Democratic tie-breaker," he said.

How effectively can we expect a tied chamber to function?

Even non-tied Senates in recent years have, more often than not, been dysfunctional. "We don’t use the term ‘efficient’ when talking about the Senate," Smith said.

Ryan called himself "skeptical" that any big and divisive legislation will get passed in a tied Senate, noting that the 60-vote threshold to move past a filibuster will remain in place for most legislative business.

"We have seen even larger majorities do not always hold together, so in each of these areas, Democrats will have to satisfy all of their members, which will likely limit their reach," Fortier said. He added that "a Senate this close would likely preclude cutting back on or eliminating the filibuster."

Democrats can take comfort that they’ll be in a stronger position to approve business that only requires a simple majority. This includes some important duties, including confirming executive-branch appointments such as cabinet secretaries, and judicial appointments, all the way up to seats on the Supreme Court.

Democrats will have to worry about defections in their own ranks, however.

Centrist Democrats "might want to avoid regular scenarios in which Harris is the defining vote. Instead, they will want to be the ones who determine Senate outcomes," Cohen said. Senate Republican moderates might feel the same impulse, he said.

CORRECTION, Jan. 7, 1:54 p.m.: This article was corrected to reflect that under the 2001 power-sharing agreement, Republicans chaired Senate committees.