Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

Rep. Bennie Thompson, D-Miss., and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi of Calif., talk to reporters on May 19, 2021, about legislation to create an independent, bipartisan commission to investigate the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol. (AP)

If Your Time is short

• Legislation to create a bipartisan, independent commission to study the events of Jan. 6 has passed the House, but it faces a tough obstacle in the Senate, where support from 10 Republicans would be needed to proceed to a vote.

• Experts say that an independent commission would be superior to the alternatives, since its membership would be one step removed from partisan politics and would have the potential to be taken more seriously.

• A congressionally created commission could subpoena former President Donald Trump and his top advisers, but under the bill, the structure of the committee would require at least one Republican member’s support for such a move, which would pose a significant obstacle.

Since Jan. 6, calls for an independent commission to investigate Capitol insurrection have been growing. Recently, all House Democrats and 35 Republicans voted in favor of a bill that sets up a commission similar to the one that investigated 9/11.

After House passage, the measure moved to the Senate, where Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., is expressing opposition. This means a blue-ribbon commission has a tough path to enactment.

If such a commission is formed, its findings could have implications for security at the Capitol and affect how lawmakers and other politicians convey messages about the riot during the midterm campaign next year.

So what would such a commission look like? What powers would it have? And if the bill to create it dies in the Senate, what are the possible alternatives for lawmakers who want to see an investigation of the events of Jan. 6?

What is in the bill that passed the House?

The bill to form the commision was sponsored by Homeland Security Committee Chairman Bennie Thompson, D-Miss., and Ranking Member John Katko, R-N.Y. It passed the House, 252-175.

Sign up for PolitiFact texts

The proposed National Commission to Investigate the January 6 Attack on the United States Capitol Complex Act would investigate the attack on the Capitol, including the preparedness and response by various law enforcement agencies and "how technology, including online platforms, financing, and malign foreign influence operations and campaigns may have factored into the motivation, organization, and execution of the domestic terrorist attack."

The commission would also investigate the sharing of intelligence information among the U.S. Capitol Police, Sergeants at Arms of the House and Senate, and local and federal law enforcement agencies, including the Metropolitan Police and the National Guard. The commission would be charged with reporting its findings to Congress and the president by Dec. 31, 2021, which may include recommendations to change laws or security procedures.

"This legislation is not about partisan politics," Katko said on the House floor. "It is about finding the truth and addressing the vulnerabilities of our security apparatus so that we can emerge stronger and better prepared."

The day before the House vote, former President Donald Trump issued a statement calling on Republicans to "not approve the Democrat trap of the Jan. 6 Commission" and said it amounted to "more partisan unfairness." The GOP House leadership opposed the measure and formally urged Republicans in the chamber to vote against it.

In the Senate, the bill will need the support of 10 Republicans to proceed to a vote. Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., has indicated he plans to bring the legislation for a vote, possibly as early as next week.

McConnell said the proposal was "slanted and unbalanced," even though the commission would be evenly split between Democrats and Republicans.

McConnell’s office pointed to the part of the bill that gives the chairperson — appointed by the Democrats — the power to appoint staff, While the bill says the chair shall consult the vice chair, McConnell’s office said that’s not good enough.

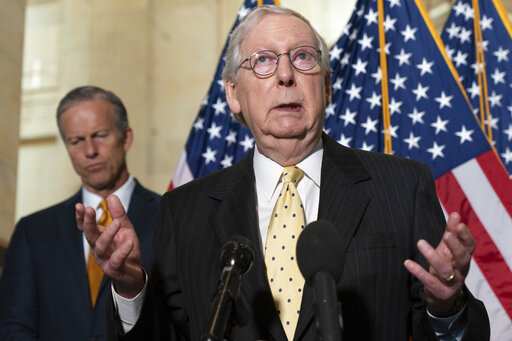

Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, right, and Sen. John Thune, R-S.D., speak to the media on May 18, 2021. (AP)

How is this commission different from existing congressional committees that are looking into Jan. 6?

Already, multiple House and Senate committees have begun their own investigations into the events of Jan. 6, and some have held public hearings with witnesses. McConnell cited the existence of these congressional probes as an argument why a new investigative forum is not needed.

However, experts see some key differences between these congressional committee probes and what a commission would do.

First, the commission would focus on a set of specific questions, unlike congressional committees, which have a broad range of legislative and oversight duties, said Matt Glassman, a senior fellow at Georgetown University's Government Affairs Institute. The commission would be created with a specific end date and have deliverables such as a final report, although the timing could slip and be readjusted.

Perhaps the biggest difference is that the commission would exclude members of Congress or other current federal officials.

The bipartisan commission would include 10 members. House and Senate leaders for the Democratic Party would appoint the commission chair and four other members, while the Republican leaders would appoint the vice chair and four other members.

"Commissions are designed to promote legitimacy of the investigation," said Andrew M. Wright, a partner at the law firm K&L Gates and a former investigations lawyer who previously worked for President Barack Obama. "Commissioners are usually at least one degree removed from partisan election campaigns. That lining of insulation allows for some space to establish politically inconvenient facts and let the evidence take the investigation wherever it leads."

Since the events of Jan. 6 involved many lawmakers as witnesses, an independent commission avoids the prospect of lawmakers having to serve the dual roles of witness and investigator, Wright said.

A related advantage of a commission model is that it would avoid the spectacle of lawmakers in either party grandstanding for the cameras during public questioning, said New York University law professor Ryan Goodman. And for Democrats, it would prevent the investigation from taking lawmakers’ time away from the work of implementing the party’s legislative agenda.

Whom can the commission subpoena, and does that include Trump?

A record of Trump’s social media statements during and after the riot already exists, but not a full accounting of his actions during the riot. Journalists and the public have been left to piece together Trump’s role that day from a hodgepodge of unofficial sources.

So could Trump be called to testify, or forced to turn over records to a commission? Theoretically yes, but given the makeup of the commission, a successful subpoena may be tough to get.

A subpoena of Trump could be possible because "the commission would have the same power that Congress has to subpoena witnesses and documents, and this would include Trump, his advisers at the time, potential confederates, and even members of Congress and their staff," said James Robenalt, a lawyer with experience in political investigations.

If Trump is subpoenaed, he could fight it in court, citing one or more types of privilege, such as executive privilege and national security privilege.

But Trump’s argument for protection would not be a slam dunk. In the case Trump vs. Vance, the Supreme Court last year ruled 7-2 against Trump’s request to protect his tax records from New York prosecutors’ subpoenas.

If anything, Robenalt said, Trump would have a weaker case in fighting a commission subpoena,, since he is no longer president; because he is now subject to prosecution, unlike when he was in the White House; and because his actions on Jan. 6 arguably relate to his role as a candidate rather than as president.

But just issuing a subpoena would face a hurdle. The bill states that the commission can issue subpoenas if the chair and vice chair agree, or by a vote by the majority of the commission. The majority requirement for a subpoena could mean that Republican appointees would be able to block a subpoena to Trump, said Mark Osler, a law professor at the University of St. Thomas.

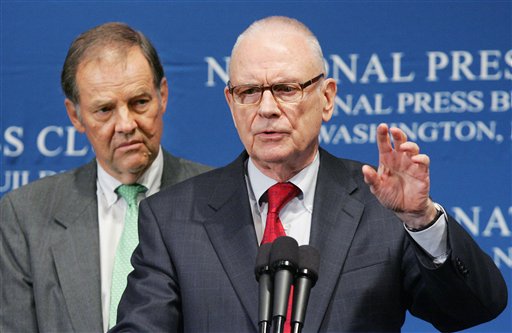

Former 9/11 Commission chairmen Lee Hamilton, right, and Thomas Kean at the National Press Club on Sept. 11, 2006, in connection with the 5th anniversary of the Sept. 11 attacks. (AP)

Has there been this type of commission before?

Broadly, the commission is modeled after the 9/11 commission, including its evenly divided membership among the two parties and its subpoena rules. The 9/11 Commission Report, published in 2004, provided a comprehensive account of the terrorist attacks from 2001 and recommendations to prevent other attacks.

Experts consider the 9/11 Commission to have achieved some success, though it also faced criticism.

On the upside, the 9/11 commission obtained some information that had escaped prior congressional efforts, including interviewing the sitting president and vice president, holding a public hearing with the sitting national security adviser, and obtaining access to the president’s daily intelligence briefs, Goodman said.

"That information alone, regardless of the commission’s final report, helped shape the public understanding of the events leading up to the 9/11 attack, and how history records it," Goodman said.

The commission was also effective in bringing in outside expertise to address complex issues, Glassman said. The 9/11 Commission "used prestige and public visibility to box Congress into making policy changes that it probably otherwise would not have made," he said.

At the same time, the 9/11 Commission "failed to identify the responsibility of senior officials for lapses in national security prior to the terrorist attack," Goodman said. "That was a deliberate choice on the part of its members, who prioritized having a unanimous report with recommendations for government reform."

Meanwhile, any policy recommendations would still have to be enacted by Congress, which may lack the political will. "Many, many congressional commissions are created specifically to help Congress abdicate responsibility on an issue," Glassman said.

How well would a 9/11 Commission-style panel work in today’s political environment?

The hyperpartisanship in Congress today will pose challenges to creating an independent commission, experts agreed.

University of Michigan professor David Wallace, who has written about the failings of the 9/11 Commission, said that a Jan. 6 commission "seems to me like a recipe for a stalemate."

"In the contemporary political environment, it will be completely infeasible that any kind of congressional investigation will be able to conduct an honest, due-diligence investigation to get at the heart of the facts of the matter," he said.

In fact, lawmakers "couldn’t even agree that was an attack on the Capitol," Wallace said, alluding to recent efforts by Republicans to downplay the severity of the attack. "I have no faith that a bipartisan commission is going to be able to breach that divide."

But a member of the 9/11 Commission, former Rep. Tim Roemer, D-Ind., said the commission model could work again, despite the obstacles.

Before he served on the 9/11 Commission, Roemer served on the House Intelligence Committee as it was probing 9/11.

"We found after eight months of committee work and congressional oversight, there were more questions than answers, and more importantly we only had jurisdiction in one area: intelligence," he said. "You need a whole-of-government approach to do this. … It’s got to work, and it can work."

Former New Jersey Gov. Thomas Kean, a Republican, and former Rep. Lee Hamilton, D-Ind. — the chair and vice chair of the 9/11 commission — wrote a letter to congressional leaders in February calling for an independent commission on the Jan. 6 attack, a position they reiterated May 19.

"Our country has been wounded," they wrote in February. "A full accounting of the events of Jan. 6 and the identification of measures to strengthen the Congress can help our country heal.

But the biggest — and perhaps most urgent — difference between the 9/11 Commission and one for Jan. 6 is that the former was largely focused on foreign terrorists, while the latter involves a barely-out-of-office president and a party he continues to influence.

The 9/11 Commision "had broad bipartisan support both within Congress and from the public and had clear national security implications that Congress welcomed help with," said Donald Wolfensberger, director of the Congress Project at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars.

If the parties can’t agree on creating a commission, what’s Plan B?

Experts told us there are several fallback options, including:

• A new, select committee of members of Congress with the specific job of investigating Jan. 6.

• A task force run by the Justice Department or a mix of agencies to propose new policies. Such a task force might have an advisory group consisting of the same types of people who might have been appointed to a blue-ribbon commission.

• Democratic congressional leaders could hire an outside investigator.

• The Justice Department could convene a grand jury and appoint a special prosecutor.

• Democrats could continue with the existing decentralized committee reviews and blame Republicans for obstructing the independent commission.

Most experts said that these solutions would be inferior, mostly due to conflicts of interest. Congressional probes would be run by lawmakers with their own agenda while others would be run by the Justice Department, which is officially part of the Biden administration.

"While commissions are far from perfect, they offer some clear benefits as a model for an after-action accounting of a national trauma," Wright said.

RELATED: What happened during the Jan. 6 call between Donald Trump and Kevin McCarthy?

RELATED: A timeline of what Trump said before Jan. 6 Capitol riot

Our Sources

C-SPAN, Rep. John Katko, R-NY, May 19, 2021

Homeland Security Committee, Press release about Jan. 6 commission, May 14, 2021

Washington Post, ‘Set up to fail’: The tortured history of the 9/11 Commission, Feb. 17, 2021

Politico, House launches wide-ranging review of federal handling of Jan. 6 insurrection, March 25, 2021

Bipartisan Policy Center, Kean-Hamilton letter to Congressional leadership, Feb. 12, 2021

Washington Post, Former leaders of 9/11 Commission call for Congress to pass measure establishing independent Jan. 6 probe, May 19, 2021

Wall Street Journal op-ed, The Jan. 6 Narrative Commission, May 18, 2021

Washington Post, Opinion: A cop’s anger at GOP lies about Jan. 6 should put Republicans on the defensive, May 14, 2021

House Homeland Security Committee, Press release, May 14, 2021

Oyez.org, "Trump vs. Vance," 2020

Congressional Research Service, "Congressional Subpoenas: Enforcing Executive Branch Compliance," March 27, 2019

Lawfare, "What’s in the Jan. 6 Commission Bill?" May 18, 2021

Lawfare, "Congressional Subpoena Power and Executive Privilege: The Coming Showdown Between the Branches," Jan. 30, 2019

Just Security, "Investigating a Crisis: A Comparison of Six U.S. Congressional Investigatory Commissions," April 6, 2021

Email interview with Justin Goodman, spokesperson for Chuck Schumer, May 20, 2021

Email interview with David Popp, spokesperson for Mitch McConnell, May 20, 2021

Interview with former Rep. Tom Roemer, D-Ind., May 20, 2021

Interview with David Wallace, University of Michigan clinical associate professor of information, May 20, 2021

Email interview with Margaret Susan Thompson, professor of history and political science at Syracuse University’s Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs, May 20, 2021

Email interview with James Robenalt, attorney with Thompson Hine LLP, May 20, 2021

Email interview with Matt Glassman, senior fellow at Georgetown University's Government Affairs Institute, May 20, 2021

Email interview with Andrew M. Wright, partner at the law firm K&L Gates, May 20, 2021

Email interview with Mark Osler, law professor at the University of St. Thomas, May 20, 2021

Email interview with Ryan Goodman, New York University law professor, May 20, 2021

Email interview with Donald Wolfensberger, director of the Congress Project at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, May 20, 2021

Email interview with Steven Smith, political scientist at Washington University in St. Louis, May 20, 2021