Get PolitiFact in your inbox.

Brochures are displayed at the Alaska Division of Elections office in Anchorage, Alaska, detailing changes to elections this year on Jan. 21, 2022. (AP)

If Your Time is short

-

Alaska has an unusual election season in 2022 that includes a special election to succeed the late U.S. Rep. Don Young. The rare open seat has drawn a 48-candidate field that includes everyone from former Gov. Sarah Palin to someone named Santa Claus.

-

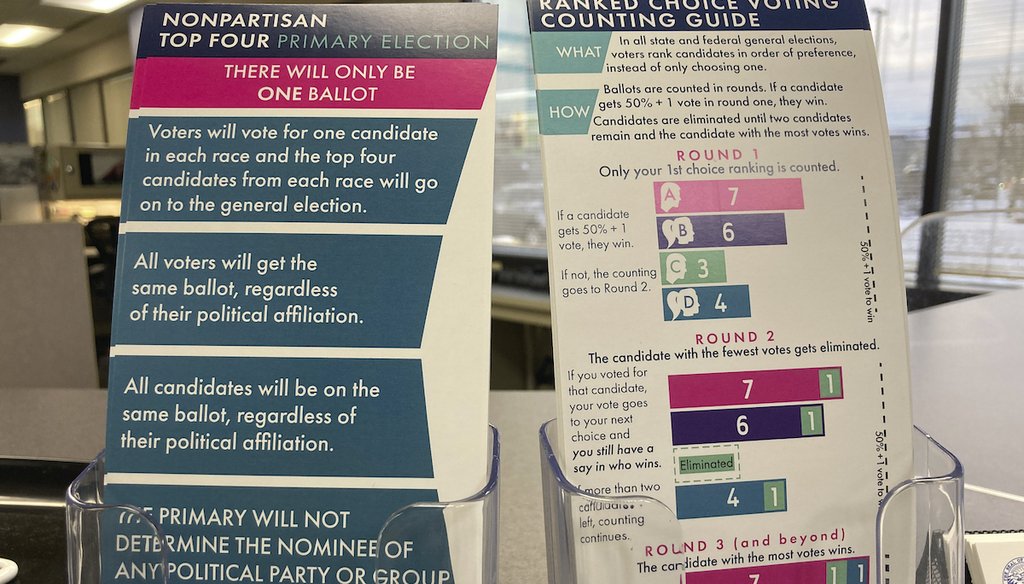

In 2020, Alaska voters approved a change in their voting system to ranked choice voting. For the general election, voters rank the candidates in order of their preference. As soon as one candidate wins 50% plus 1, they win, going as many rounds as it takes.

-

Ranked choice voting has previously been used in Maine as well as multiple cities as varied as jurisdictions in Utah to New York City.

Alaska voters in 2022 will use a new method to choose their representation in Congress, one that eliminates traditional primaries. The design, called ranked choice voting, is gaining popularity in many places nationwide.

Ranked choice voting is a system by which voters rank candidates in descending order of preference, rather than choosing a single candidate. It has been used by cities of varying political stripes, from New York City to Utah. Alaska is the second state to implement it after Maine.

States, through their legislatures and governors, typically set laws for how their residents can vote. In addition, some states allow voters to approve policies by referendum. That’s what happened in Alaska in 2020, when voters narrowly voted to establish an all-party primary followed by a ranked choice general election among the top four primary finishers.

Alaska will use ranked choice voting in the election to fill the seat left vacant after U.S. Rep. Don Young died in March. It will also be used for the U.S. Senate election in which Republican incumbent Lisa Murkowski faces a challenge from Trump-backed Republican Kelly Tshibaka.

Democracy experts say ranked choice voting makes it less likely that an ideologically extreme candidate can prevail by winning a small plurality of the vote in a crowded primary. In such cases, a majority of voters, sometimes a large majority, had voted for candidates other than the eventual winner.

"This reform aims to increase the likelihood that candidates with the broadest appeal to voters, rather than more factional candidates, will win the election," wrote Richard Pildes, a professor at New York University’s School of Law.

FairVote, the leading national group that supports ranked choice voting, found that between 1992 and 2019, 49 senators have been elected with less than 50% support. In fact, in Alaska, no candidate has garnered more than 50% of the vote in the general election for a U.S. Senate seat since 2002.

"As a result, Alaska elections are not as representative as they should be, and in a state with a long history of viable third-party and independent candidates, it’s not always clear that winning candidates have the support of most Alaska voters," Alaskans for Better Elections said.

How will ranked choice voting work in Alaska this year?

Alaskans have an especially busy election season ahead of them due to Young’s death. Young was an iconoclastic congressman who served as the state’s sole House member since 1973. Over the next few months, Alaskans will vote four times for Young’s seat.

First, they will vote on June 11, in an all-mail election, in a special primary to fill the remainder of Young’s term, which ends in January. The state will send out mail ballots to all voters April 27.

On this ballot, there will be 48 candidates, including former Republican Gov. Sarah Palin; Nick Begich III, a Republican from a well-known Alaska family of Democratic politicians; Al Gross, a nonpartisan candidate who ran for the U.S. Senate as a Democrat in 2020 but lost to Republican Dan Sullivan; and state Sen. Josh Revak, who has been endorsed by Young’s widow.

Also on the ballot: An Alaskan named Santa Claus, who is both a member of the North Pole City Council and an independent who aligns himself with Sen. Bernie Sanders.

The primary includes candidates of all parties, which means that any mix of four candidates — no matter their party affiliation — would advance to the Aug. 16 general election.

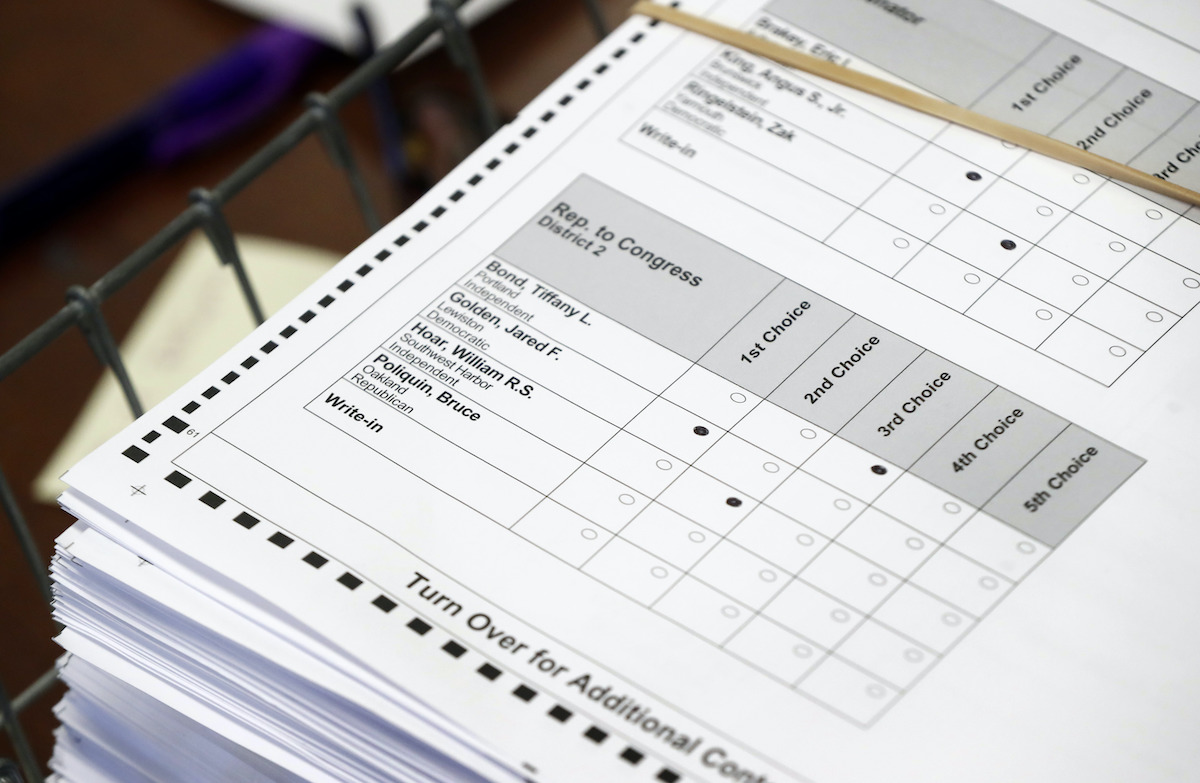

In the general election, voters will rank the four candidates in order of preference by filling out ovals on the ballot for first choice, second choice, third choice, and fourth choice. If one candidate receives more than 50% of first-choice votes on the initial count, then that candidate wins. If no candidate meets that threshold, then the counting goes to additional rounds.

The last place candidate in round one is eliminated and their voters’ second choice selection is reallocated to the remaining candidates on the ballot. This vote redistribution process continues until one candidate exceeds 50% of the vote. (The Alaska Division of Elections shows examples of the right and wrong way to fill out a ranked choice ballot.)

Making things somewhat more confusing, on Aug. 16, the same day that Alaskans vote in the special election for Young’s seat, they will also vote in the primary election for the full two-year term that starts in January 2023.

Meanwhile, in the U.S. Senate primary, roughly one dozen candidates are running — about half of them Republicans, while the rest are either undeclared, nonpartisan or other affiliations. No Democrats have declared for the seat. (In Alaska, slightly more than half of the electorate is not registered with the Republican or Democratic parties.)

The only two Senate candidates who have raised significant funds are Murkowski and Tshibaka. Trump endorsed Tshibaka after Murkowski voted to impeach him after the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol. Tshibaka worked most recently for two years as the commissioner for the Alaska Department of Administration after a career as a lawyer in D.C. for the Postal Service Inspector General and federal agencies.

Some political observers say that Murkowski faced the prospect of losing a Republican primary under the old system. In 2010, she came close to losing, as she was defeated in the Republican primary by Tea Party favorite Joe Miller. Murkowski retained her seat by mounting a successful write-in campaign.

"In a Republican primary, the favored candidate was the person who appealed to the party stalwarts and followed the direction of the party at that time which has gotten progressively more conservative," said University of Alaska political scientist Jerry McBeath.

Speculation about what would have happened to Murkowski without ranked choice voting aside, this much is agreed upon: She is expected to advance from the primary as one of the top four vote-getters.

"If she retains that broad appeal, her re-election prospects would be strong under the state’s reforms," Pildes wrote in the New York Times. "In the general election, if Ms. Murkowsi is the first choice of many and the second choice of enough independents, Democrats and Republicans, Alaska’s new system will ensure she will be re-elected."

Where has ranked choice voting been used already?

Ballots are prepared for recounting in Maine's 2nd Congressional District, Thursday, Dec. 6, 2018, in Augusta, Maine. (AP)

Maine used ranked choice voting for the first time in 2018 for state and federal elections for Congress. Around the country, one county and 52 cities are expected to use ranked choice voting in 2022. In Utah, 23 cities and towns used ranked choice voting in a pilot program in 2021.

New York City in 2021 became the largest city to use ranked choice voting. In all but three of the 63 races, the candidate who won the largest number of votes on the first ballot ultimately won the election, Politico found. That’s in line with ranked choice voting races nationally, FairVote found.

The idea of ranked choice voting has faced some resistance. Tennessee Gov. Bill Lee signed a bill this year that bans ranked choice voting, ending a longstanding feud with the city of Memphis, which sought to use it. Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis signed SB 524, which bans ranked choice voting and creates the Office of Election Crimes and Security. In 2020, Massachusetts voters rejected a proposal to use ranked choice voting statewide. Gov. Charlie Baker, a Republican, portrayed it as a complicated method of voting and opposed it.

What are the benefits and downsides to ranked choice voting?

Supporters of ranked choice voting say it encourages candidates to appeal to a broad spectrum of voters rather than an extreme slice of the electorate, that it encourages civility in campaigns and that it promotes fuller participation.

Opponents say that ranked choice voting doesn’t meet all of its goals and introduces a new set of challenges.

Ranked choice voting is designed to give some juice to the middle of the electorate, said Dan Shea, a government professor at Colby College in Maine.

"Extremists will not like ranked choice voting; they get purged rather quickly," Shea said. "The only exception is if a large swath of the electorate is also extreme."

Glenn Youngkin, now governor of Virginia, won a ranked choice Republican primary over a more extreme candidate then went on to defeat Democratic candidate Terry McAuliffe in an upset.

The Virginia Republican Party in 2021 held a convention where delegates listed their preferences in ranked order for seven candidates for governor and required the nominee to receive a majority, wrote two political science professors at University of Massachusetts, Raymond J. La Raja and Alexander Theodoridis.

Youngkin led in the first round with 33% and in the last round won with 55%. The process eliminated Sen. Amanda Chase, who called herself "Trump in heels" and falsely blamed antifa and Black Lives Matter for the attack on the U.S. Capitol and was censured – including by some in her own party – by the state senate.

"Had the Virginia GOP held an ordinary primary, Chase might well have won — or at least, her attacks on Youngkin might have left him wounded in the general election," wrote La Raja and Theodoridis. "In the end, Youngkin straddled quite deftly the Trump-loving base and pragmatic GOP-leaning voters in the suburbs, even as he made headway with persuadable independent voters."

In Republican-dominated Utah, ranked choice voting has been used in state and county party elections for two decades, wrote Stan Lockhart, a former Republican Party chair in Utah and director of Utah Ranked Choice Voting.

Traditionally, Utah voters would go to the polls twice in local elections, but cities that used ranked choice go to the polls only once, Lockhart wrote, "shortening the campaign season and reducing the cost to taxpayers."

"Ranked choice voting is also an overall better experience for the voter," Lockhart wrote. "With RCV, you can vote your conscience and rank each candidate by preference, without strategically voting for the ‘lesser of two evils’ or worrying about vote splitting and so-called ‘spoiler’ candidates. RCV simply cures those problems. Now you can vote for someone and not against someone."

One of the main criticisms of ranked choice voting are "exhausted ballots," which happen when voters fail to rank enough candidates.

Nolan McCarty, a professor of politics and public affairs at Princeton University, found that voters rarely rank a sufficient number of candidates, leading to the discarding of over 20% of ballots.

A 2021 review of the literature on ranked choice voting by New America found that young voters and Democrats appear more open to ranked choice voting than older voters and Republicans.

However, many of the promised benefits are more modest than originally hoped or difficult to quantify, the report found. Some political observers have speculated that voters may be confused by the new way of voting, but some polls debunk that notion. In Utah, a poll found that 81% of respondents reported it was easy to use ranked choice voting.

"Of course Alaskans understand it. They voted for it," Jason Grenn, executive director of Alaskans for Better Elections, told the Alaska Land Mine website. But Grenn said that "anything that’s new, it takes them hearing and seeing something a few times before they get it."

RELATED: What can the federal government do right now to protect voting rights before the 2022 midterms?

Our Sources

Alaska Division of Elections, Nonpartisan top four primary election FAQ, 2022

Alaska Division of Elections, Primary candidate list, 2022

Open Secrets, Alaska Senate candidates, 2022

Alaska Public Radio, Sorting the 48 Alaska candidates running in the special US House election, April 4, 2022

Alaska Dispatch News, Alaska's U.S. House race includes 48 candidates and a lot of uncertainty, April 4, 2022

Alaskans for Better Elections, How Ranked Choice Voting Works, Accessed 2022

Alaska Land and Mine, Is Alaska ready for ranked-choice voting? April 4, 2022

KUAC, Weird things to know about Alaska's Special Primary Election to fill what will be five months of Don Young's last term. April 4, 2022

New York Times op ed by New York University law professor Richard Pildes, More Places Should Do What Alaska Did to Its Elections, Feb. 15, 2022

Washington Post op ed by law professor Ed Foley, Opinion: Can Alaska save democracy? Feb. 10, 2022

Tennessean, Bill banning ranked choice voting in Tennessee advances, even as advocates seek court relief on method, Feb. 8, 2022

Stan Lockhart, former Republican Party chair in Utah and directs Utah Ranked Choice Voting, Before any ban, Florida should first look at Utah’s successful ranked choice voting, Feb. 6, 2022

Sarasota Herald Tribune, Sarasota City Commission may pause plan for advancing ranked-choice voting, Sept. 22, 2021

Washington Post, How ranked-choice voting could change the way democracy works, June 21, 2021

Huffington Post, Maine Is About To Try Out A New Way Of Electing Politicians, June 7, 2018

Sutherland Institute, The Benefits and Drawbacks of Ranked-Choice Voting in Utah, 2022

Facebook video, Jane Kim and Mark Leno – Standing Together, May 10, 2018

Politico, New York's first full ranked-choice election changed campaigns — if not the results, Aug. 24, 2021

New America, What We Know About Ranked-Choice Voting, Nov. 10, 2021

Governing, Can Ranked Choice Voting Transform Our Democracy? May 27, 2021

PolitiFact, Dragoo jumps the gun; ranked-choice voting is still up for debate, Sept. 29, 2020

Email interview, Cynthia McClintock, professor of political science and international affairs, George Washington University, April 19, 2022

Email interview, Rob Richie, FairVote president, April 18, 2022

Email interview, Lee Drutman, Senior Fellow, New America | Political Reform Program, April 19, 2022

Email interview, David Kimball, political science professor and interim department chair at University of Missouri - St Louis, April 11, 2022

Email interview, Tiffany Montemayor, Alaska Division of Elections spokesperson, April 11, 2022

Telephone interview, University of Alaska political scientist Jerry McBeath, April 19, 2022