Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

Special counsel Jack Smith speaks about an indictment of former President Donald Trump on Aug. 1, 2023, at the Department of Justice in Washington. (AP)

The third indictment of former President Donald Trump — for his actions leading up to and on Jan. 6, 2021 — examines a broad swirl of Trump’s post-2020 election activities and consolidates it into four charges.

The indictment casts Trump, aided by a half-dozen co-conspirators, as knowingly making false claims in a bid to keep the presidency. This portrayal of his actions makes it clear that the prosecution does not believe Trump was duped by advisers or acting delusionally, but rather knew that what he was saying was false and kept spreading the claims anyway.

The indictment is another in a historic list. Trump was the first U.S. president to be indicted; it’s his second federal indictment and third overall. Trump — the front-runner for the 2024 Republican presidential nomination — remains at risk of a fourth indictment in Fulton County, Georgia, over post-election phone calls he made to Georgia state officials and other efforts to overturn the presidential election.

Structurally, the indictment offers a unified narrative, dividing Trump and his allies’ activities into four major phases. The activities start shortly after Election Day in 2020 and end with the storming of the U.S. Capitol, with Trump trying to enlist the aid of everyone from state elected officials to Justice Department officials and his own vice president, Mike Pence. Many of these people, including Pence, refused his demands.

"This indictment is the ultimate criminal prosecution from a legal, political, historical and constitutional perspective," said Bradley Moss, a national security lawyer in Washington, D.C.

The indictment was released Aug. 1 following an investigation headed by Special Counsel Jack Smith. Trump has denied wrongdoing.

Here, we’ll examine the indictment’s details.

What is Trump charged with?

The indictment includes four counts.

One is a charge of conspiracy to defraud the United States (18 U.S. Code § 371). It alleges that Trump and others "conspire(d)" to "obstruct" and "defeat" the "lawful federal government function by which the results of the presidential election are collected, counted and certified by the federal government." This included actions both before Jan. 6, when the electoral votes were being certified by states, and on Jan. 6, when they were to be counted in Congress.

Another charge is conspiracy to obstruct an official proceeding (18 U.S. Code § 1512). It says that Trump and his co-conspirators worked to obstruct the electoral vote’s congressional certification Jan. 6.

This law has been used successfully to prosecute hundreds of people who entered the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6. In April, a federal appeals court, in a 2-1 decision, upheld the use of this provision in Jan. 6-related prosecutions.

A third charge alleges a conspiracy against constitutional or statutory rights (18 U.S. Code § 241). It says Trump conspired with others "to injure, oppress, threaten, and intimidate" a constitutional and statutory right — "the right to vote, and to have one's vote counted."

The law originally was enacted to strengthen enforcement of Reconstruction-era laws after the Civil War. But it has been used for decades in election-related cases, bolstered by a 7-2 Supreme Court decision in the 1974 case Anderson v. United States.

A conspiracy involves an agreement between at least two people to commit a crime, with at least one co-conspirator taking at least one overt action to further the conspiracy. The indictment says that collectively, the three conspiracies Trump is accused of "targeted a bedrock function of the United States federal government: the nation's process of collecting, counting, and certifying the results of the presidential election."

The underlying crime for these conspiracies is cited in a fourth charge — a different portion of 18 U.S. Code § 1512 — of obstructing or trying to obstruct an official proceeding, the Jan. 6 counting of the electoral votes. A conspiracy’s goal need not be achieved to prosecute.

"Conspiracy is an extremely common charge in almost any criminal case involving multiple actors," Randall D. Eliason, a former federal prosecutor who is now a lecturer at George Washington University’s law school, wrote recently. "It’s a great vehicle for prosecutors to use to lay out an entire criminal scheme, identifying all the actors and everything that they did."

Former Arizona state House Speaker Rusty Bowers testifies before a House select committee investigating the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol. (AP)

The four phases of Trump’s efforts, according to the indictment

The bulk of the indictment is a step-by-step presentation of evidence. This narrative is included under the heading of the first count; the listing of the other three counts point mostly back to evidence offered to support the first count.

The indictment lays out four phases of the conspiracy.

• Urging state officials to "subvert the legitimate election results and change electoral votes."

This involved efforts by Trump and his allies to ask state officials to change electoral slates from Joe Biden to Trump. The scheme involved communicating with state lawmakers and filing lawsuits alleging unsupported voter fraud allegations.

Arizona: On Nov. 22, 2020, Trump called the speaker of the Arizona House of Representatives, Rusty Bowers, and falsely claimed election fraud. Bowers rejected Trump and his allies’ efforts to deliver the electoral votes to Trump.

Georgia: Trump’s agents gave a presentation before a Georgia senate committee, falsely alleging voting by dead people and "suitcases" full of illegal ballots being counted at the State Farm Arena. Trump also called Georgia’s attorney general to pressure him to support an election lawsuit in another state.

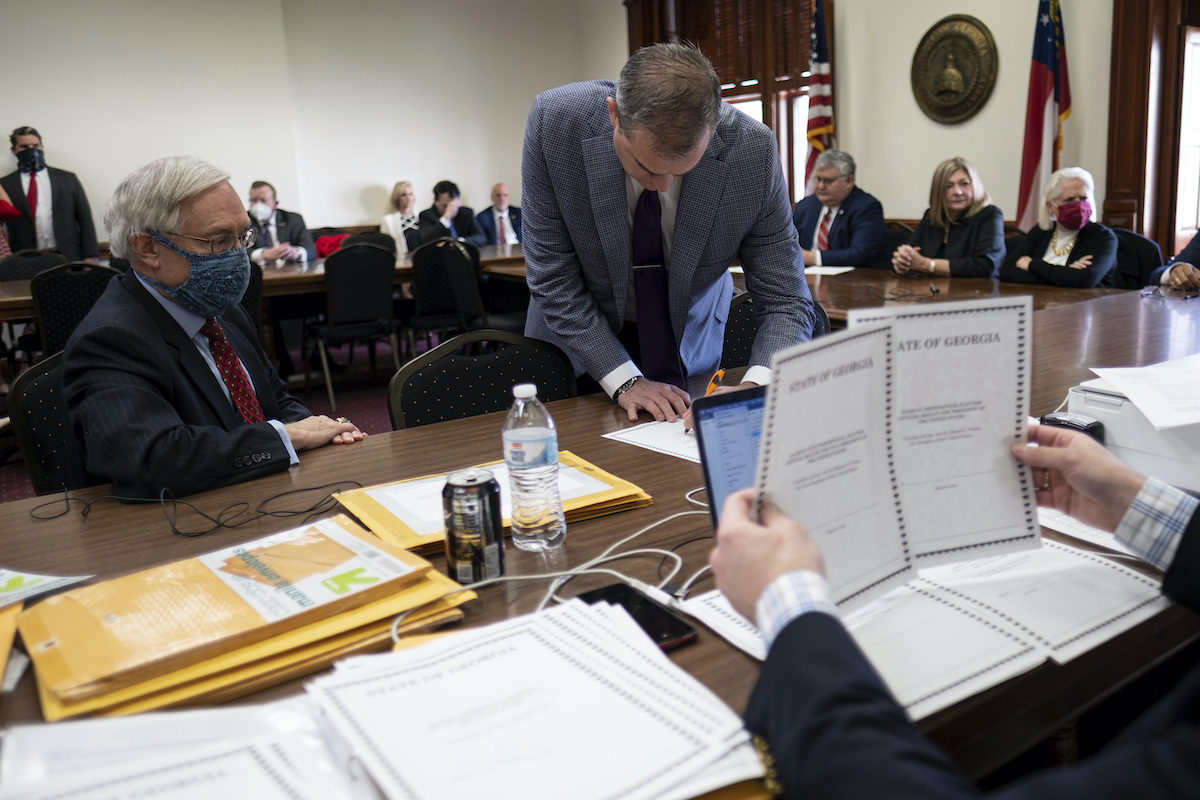

An alternate slate of electors nominated by the Republican Party of Georgia cast electoral votes for President Donald Trump at the Georgia State Capitol on Dec. 14, 2020 at the same time the official Democratic electors met. (AP)

On Jan. 2, 2021, Trump had an hourlong phone call pressuring Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger to act. Trump said he wanted to "find 11,780 votes," which was one more than his losing margin.

Michigan: Trump met in the Oval Office on Nov. 20, 2020, with Michigan House and Senate leaders and alleged an illegal vote dump in Detroit. The Michigan officials rejected Trump’s claims. Numerous false claims alleging illegal late at night dumps of ballots in favor of Biden were debunked.

Pennsylvania: A co-conspirator held an event with state legislators at a Gettysburg hotel and made false claims about missing absentee ballots. Days later, Republican legislature leaders said they lacked authority to appoint their own electors. Trump retweeted a post calling the legislators cowards.

Wisconsin: The state Supreme Court rejected an election challenge in December 2020; the governor then signed a certificate identifying Biden’s electors Dec. 21. Trump tweeted calling on Republicans to "overturn this ridiculous State Election."

Attorney John Eastman, the architect of a legal strategy aimed at keeping former President Donald Trump in power, faces reporters in Los Angeles on June 20, 2023. (AP)

• Establishing fake electors and having them transmit false certificates to Congress.

This effort, which Trump and his allies characterized as "alternate" electors, was designed to create a pretext for Pence to count ballots cast by Trump-aligned electors, the indictment says.

John Eastman, a Trump-aligned lawyer, wrote a memo explaining a "Jan. 6 scenario" based on the submission to Pence of seven dual slates of electors. Eastman proposed that Pence announce that he had multiple slates of electors and, because of disputes in seven states, no electors from those could be valid. The indictment states that there were multiple memos sent by co-conspirators to the targeted states.

In a group text with other campaign officials, one campaign official called it a "crazy play so I don’t know who wants to put their name on it."

The Trump campaign didn’t hide this strategy. Stephen Miller, a Trump campaign official, said Dec. 14, 2020, on Fox News that "as we speak today, an alternate slate of electors in the contested states is going to vote, and we are going to send those results up to Congress."

• Attempts to "leverage the Justice Department to use deceit" to replace legitimate electors with fake Trump electors.

In late December 2020, a co-conspirator asked Justice Department officials to write a letter to officials in targeted states to get them to replace Biden’s electors. A co-conspirator sent a draft letter to top Justice Department officials and asked them to sign it. They refused.

On Dec. 31, Trump summoned top Justice Department officials to the Oval Office and "raised claims about election fraud that Justice Department officials had already told him were not true." He also suggested he might change the department’s leadership. Trump on Jan. 3 met again with top Justice Department officials and "expressed frustration with the Acting Attorney General for failing to do anything to overturn election results."

• Efforts to enlist Pence to "fraudulently alter the election results" on Jan. 6.

This includes Trump and his allies’ efforts to persuade Pence behind the scenes to accept the fake electors, or to send electoral slates back to the states for reconsideration. This also includes Trump’s efforts to "use a crowd of supporters" on Jan. 6 to pressure Pence.

"When advisors urged the Defendant to issue a calming message aimed at the rioters, the Defendant refused, instead repeatedly remarking that the people at the Capitol were angry because the election had been stolen," the indictment says.

The evidence for this period includes contemporaneous notes Pence took that had not previously been revealed to the public.

What defenses could Trump employ?

Within hours of the indictment’s release, Trump’s lawyers were already road-testing one defense in television interviews: that Trump was within his First Amendment rights.

The indictment acknowledges that Trump had a First Amendment right to free speech, but argues that his actions went well beyond speech.

"Shortly after election day," the indictment says, Trump "pursued unlawful means of discounting legitimate votes and subverting the election results."

The indictment also notes that Trump had a legitimate path for making his arguments: filing lawsuits for perceived election shortcomings. The indictment notes that Trump used that option, but consistently lost in court.

Meanwhile, Trump allies may cite a "precedent" from a half-century ago.

His allies have tried to draw parallels between the 1960 and 2020 elections. Hawaii’s vote count in 1960 was too close to call, with Republican Richard Nixon holding a small lead pending a recount.

Democratic electors cast their votes for John F. Kennedy Jr., and although that was premature, the recount later showed that Kennedy had won narrowly.

One key difference between the examples, however, is that in 1960, reasonable doubt about the outcome existed when the Democratic certificates were filed. A judge confirmed that the Democratic electors proceeded legally. Eventually, while Nixon, then the vice president, was presiding over the Electoral College count, he accepted the certified Democratic slate, saying it "properly and legally portrays the facts with respect to the electors chosen by the people of Hawaii."

What’s not included in the indictment

The indictment did not include seditious conspiracy charges (18 U.S. Code § 2384), which have been used against Trump-allied groups such as the Oath Keepers and the Proud Boys. Those charges would have been harder to prosecute in Trump’s case because it would be harder to prove a direct link between Trump and violent acts.

The only person charged in the indictment is Trump. But it lists six unnamed "co-conspirators," who could later face charges.

Prosecutors may have made deals with some of the co-conspirators or don’t want the complications of a case with multiple defendants, said Joan Meyer, a partner at the law firm Thompson Hine LLP.

Trump will face additional legal hurdles if the Georgia indictment comes to fruition, said Mark Osler, a University of St. Thomas law professor.

"It will be very hard, and expensive, to defend both at once, given the very different jurisdictions, rules, and personalities in play."

RELATED: Who is Jack Smith, special counsel for Trump classified documents, 2020 election indictments?

Our Sources

Indictment of Donald Trump for the events of Jan. 6, 2021

ABC News, "Trump lawyer calls indictment an 'attack on free speech and political advocacy,'" Aug. 1, 2023

Randall Eliason, "The Charges in Trump's Target Letter: Here's what the indictment might look like," July 20, 2023

Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington, "What Trump’s federal indictment for attacks on the 2020 election could look like," July 17, 2023

New York Times, "Potential Trump Charges Include Civil Rights Law Used in Voting Fraud Cases," July 19, 2023

Associated Press, "Far-right influencer convicted in voter suppression scheme," March 31, 2023

Complaint and affidavit in support of an arrest warrant, U.S. vs. Douglass Mackey, Jan. 22, 2021

Politico, "4 more Oath Keepers found guilty of seditious conspiracy tied to Jan. 6 attack," Jan 23, 2023

PolitiFact, "Which charges could be in a Jan. 6 indictment of Donald Trump?" July 26, 2023

PolitiFact, What you need to know about the fake Trump electors, Jan. 28, 2022

Arizona House Speaker Rusty Bowers, Speaker Bowers Addresses Calls for the Legislature to Overturn 2020 Certified Election Results, Dec. 4, 2020

Trump Twitter Archive, Dec. 6, 2020 and Dec. 21, 2020

Email interview with Randall D. Eliason, former federal prosecutor and now a lecturer at George Washington University’s law school, July 20, 2023

Email interview with Joan Meyer, partner at the law firm Thompson Hine LLP, Aug. 2, 2023

Email interview with James Robenalt, partner at the law firm Thompson Hine LLP, Aug. 2, 2023

Email interview with Mark Osler, law professor at the University of St. Thomas, Aug. 1, 2023

Email interview with Bradley P. Moss, partner with the law firm Mark S. Zaid, P.C., Aug. 1, 2023