Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

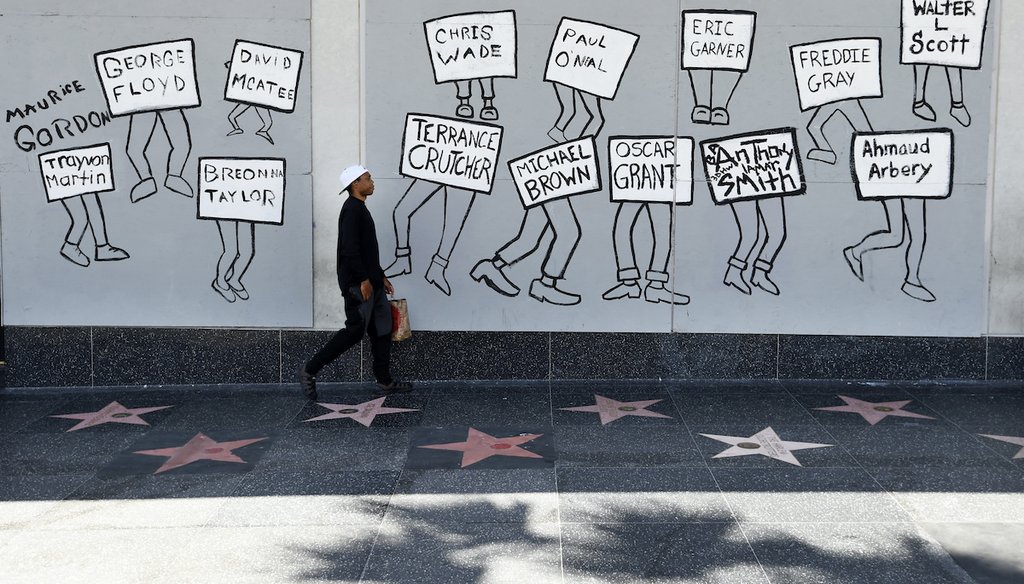

A man walks past a mural of black victims of police brutality on Hollywood Boulevard in Los Angeles on June 15, 2020, a day after a large protest march there. (AP)

If Your Time is short

-

There is no reliable, government-sponsored national data collection system that tracks fatal encounters with police.

-

Police officers who use fatal force are rarely prosecuted. But incomplete data makes it hard to determine how many of the incidents are legally justifiable.

-

Since the beginning of 2005, 172 officers have been arrested for murder or manslaughter resulting from an on-duty shooting, said Philip Stinson, professor in the criminal justice program at Bowling Green State University.

After George Floyd died at the hands of police, federal lawmakers tried and failed to pass police accountability legislation. Following the January police beating death of Tyre Nichols, some want to try again.

In interviews Feb. 5 on CBS’ "Face the Nation," four freshmen representatives debated how Congress should address crime and police accountability. Rep. Summer Lee, D-Pa. said that the subjects are intertwined.

"We cannot say that we care about crime but then do nothing, choose to do nothing, over and over and over when the crime is committed by a police officer," Lee said. "There are statistics that show that less than 2% of police officers who are engaged in misconduct are ever indicted at all."

Lee then mentioned the names of several people who died after police encounters, which provided a hint that by "misconduct" she meant people who were killed by police. But she did not directly define "misconduct."

A spokesperson for Lee referred us to a 2021 article by Vox headlined: "Police officers are prosecuted for murder in less than 2 percent of fatal shootings."

Police officers who use fatal force are rarely prosecuted, said Jessica Huff, an assistant criminology professor at the University of Nebraska. But incomplete data makes it hard to determine how many of the incidents are legally justifiable. That means that "any estimate of what percentage of officers are prosecuted could be misleading," Huff said.

"We can say what percentage of all fatal police use-of-force incidents result in prosecution, but we can’t say what percentage of criminal fatal police use-of-force incidents result in prosecution," Huff said. "We just do not have good enough data to create an accurate denominator to answer the second question."

Data on fatal police shootings shows officers are rarely charged, but the data is limited

Protesters gather on Jan. 27, 2023, in Memphis, as authorities were set to release police video of the beating of Tyre Nichols, whose death resulted in murder charges and provoked outrage at the country's latest instance of police brutality. (AP)

Criminologists have told us that the biggest issue with evaluating police use of deadly force is the lack of a reliable, government national data collection system. The data that federal agencies collect appears to reflect a significant undercount. That’s why academics, journalists and activists have created their own databases.

The Washington Post in 2015 started a project focused on tracking fatal shootings by police officers. Researchers mine local news reports, law enforcement websites and databases such as Fatal Encounters for relevant information. The Post’s database shows that police shoot and kill more than 1,000 people a year, and that about 83% of the victims were armed while 6% were not (the remainder were either unknown, undetermined or carried a replica weapon).

The Vox article cited research by Philip Stinson of Bowling Green State University in Ohio. Stinson studies crime committed by nonfederal officers. In 2004, Stinson started a project to find cases in which officers had been arrested for crimes. Stinson and his researchers get tips on cases from news reports and gather information from police or court records and publish the numbers in a database.

Stinson found that since the beginning of 2005, 172 officers have been arrested for murder or manslaughter resulting from an on-duty shooting. In 123 of the since-concluded criminal cases, 55 officers were convicted; 68 were not.

Using The Washington Post’s shootings database and his own data, Stinson said "we find that just under 2% of the on-duty officers who shoot and kill someone are charged with murder or manslaughter," in any given year.

Stinson’s sheer numbers have often been quoted by media outlets including The New York Times, CNN and PolitiFact. However Stinson said the 172 cases don’t represent enough data for peer-reviewed journals.

Two professors – Justin Nix, a criminologist at the University of Nebraska and Geoff Alpert, a criminologist at the University of South Carolina – told us that Stinson’s data are the best available. However, they expressed caution about using the numbers to make a sweeping statistical statement about officer prosecutions.

"I can’t say for sure how many are unjustified, but we can’t simply divide the number of indictments by ALL shootings and then make the jump to ‘less than 2% of officers who kill are prosecuted for murder,’" Nix said in an email. "What we WANT to know is: how often are officers charged when they use unjustified deadly force (i.e., when they commit criminal homicide)? The answer is unknown."

Although we have data that tells us whether agencies determine a shooting to be justified, we don’t know how many of those resulted in a finding of liability in civil court or if officers were later indicted, Alpert said.

"We just don't have the proper, reliable data to make such a specific finding," he said.

Even if a person who was shot by police was armed, that doesn’t necessarily make the shooting justifiable, said Greg Ridgeway, chair of the University of Pennsylvania’s criminology department and a statistics/data science professor.

"For example, if the individual fired their gun and then set it down and put their hands up … no more threat, no more justification to shoot," he said.

The website Fatal Encounters, launched by a journalist in 2012, used crowdsourced information, public records and news reports, and covered 2000 to 2021.

That website shows that in about 62% of the incidents, the civilian was pointing a gun, attacking, or shooting. That alone doesn’t mean that law enforcement acted justifiably, but it is unlikely that these incidents would rise to the level of criminal conduct, Ridgeway said.

Thaddeus Johnson, a former Memphis police officer who is now an assistant professor of criminology at Georgia State University, said that Fatal Encounters is probably the best data source on police-caused deaths — and its data on the legality of deaths come with many disclaimers.

"All of this is to say that given the data and what we know, I personally would not be comfortable making a public statement about the justifiability of any level of force used in the U.S. — lethal or otherwise," Johnson said. "We don't have data to judge the reasonableness of police force usage nationally. That said, I cannot say whether so few officers are prosecuted because most are deemed legally justified or for some other reason."

Johnson said that Lee’s statement that "less than 2% of police officers who are engaged in misconduct are ever indicted" is not supported by national data and misleads by not providing full context.

David Rudovsky, a Pennsylvania lawyer who has been involved in multiple civil lawsuits against police officers, said there are multiple reasons why prosecutors sometimes don’t bring cases or get convictions.

The cases are initially investigated by the officers’ own police departments. Officers have rights through their union contracts and may go unquestioned by the agency for months while other witnesses are interviewed. Also, Rudovsky said, jurors tend to give police officers the benefit of the doubt. Finally, by nature of their day-to-day work with police, prosecutors may be reluctant to pursue such cases.

"A lot of prosecutors, unless it was the most heinous case, the clearest case, are going to give a pass," he said.

RELATED: Ask PolitiFact: Are more people dying at the hands of law enforcement now than ever?

RELATED: What’s the ‘determinant’ in police use of force cases: The civilian's race or the officer's?

Our Sources

CBS Face the Nation, Video and transcript, Feb. 5, 2023

Bowling Green State University, The Henry A. Wallace Police Crime Database, Accessed Feb. 6, 2023

Bowling Green State University, Police integrity research group, Accessed Feb. 6, 2023

Vox, Police officers are prosecuted for murder in less than 2 percent of fatal shootings, April 2, 2021

The Washington Post, 1,110 people have been shot and killed by police in the past 12 months, Updated Jan. 25, 2023

Mapping Police Violence, database, accessed Feb. 3, 2023

The New York Times, Few police officers who cause deaths are charged or convicted, Sept. 24, 2020

CNN, Why it’s rare for police officers to be convicted of murder, April 21, 2021

PolitiFact, The guilty verdict against Derek Chauvin, explained, April 20, 2021

Legal Information Institute, excessive force, accessed Feb. 3, 2023

Philip Stinson, professor in the criminal justice program at Bowling Green State University, On-Duty Shootings: Police Officers Charged with Murder or Manslaughter, 2005-2023, Updated Jan. 31, 2023

Email interview, Emilia Rowland, spokesperson for Rep. Summer Lee, Feb. 6, 2023

Email interview, Philip Stinson, professor in the criminal justice program at Bowling Green State University, Feb. 6, 2023

Email interview, Geoffrey Alpert, a professor of criminology and criminal justice at the University of South Carolina, Feb. 6, 2023

Email interview, Justin Nix, associate professor school of criminology and criminal justice at the University of Nebraska at Omaha, Feb. 6, 2023

Email interview, Jessica Huff, assistant professor school of criminology and criminal justice at the University of Nebraska at Omaha, Feb. 6, 2023

Email interview, Kate Levine, a professor at the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law in New York who studies police prosecution, Feb. 6, 2023

Email interview, Greg Ridgeway, criminology department chair and professor in the department of statistics and data science at the University of Pennsylvania, Feb. 6. 2023

Email interview, Thaddeus Johnson, former Memphis, Tennessee, police officer and assistant professor of criminology at Georgia State University, Feb. 6, 2023