Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

Rep. Byron Donalds, R-Fla., speaks March 3, 2023, at the Conservative Political Action Conference at National Harbor in Oxon Hill, Md. (AP)

Rep. Byron Donalds, R-Fla., a prominent supporter of former President Donald Trump, recently tried to draw Black voters to Trump’s side, but a comparison he made involving the Jim Crow era drew criticism from Democrats.

At a June 4 event in Philadelphia, Donalds compared today’s Black culture with that of the Jim Crow era, when Black people in the South were subject to multiple forms of state-sponsored discrimination. Jim Crow laws were enacted over several decades following the end of post-Civil War Reconstruction in the late 19th century and formally ended with passage of the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act in the mid-1960s.

"You see, during Jim Crow, the Black family was together," Donalds said in a recording published by the Philadelphia Inquirer. "During Jim Crow, more Black people were not just conservative — Black people have always been conservative-minded — but more Black people voted conservatively. And then (the Department of Health, Education and Welfare), Lyndon Johnson — you go down that road, and now we are where we are."

Donalds’ mention of Johnson refers to increased federal efforts to fight poverty, which some conservatives say provided incentives for the breakup of families.

Leading Democrats criticized Donalds’ statement as lionizing the Jim Crow era. House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries of New York, called out Donalds on the House floor, saying his comparison was a "factually inaccurate statement that Black folks were better off during Jim Crow. That’s an outlandish, outrageous and out-of-pocket observation."

The Congressional Black Caucus, which consists of House Democrats, demanded that Donalds apologize to Black Americans "for misrepresenting one of the darkest chapters in our history for his own political gain."

Vice President Kamala Harris weighed in May 10, saying, "It’s sadly yet another example of somebody out of Florida trying to erase or rewrite our true history," referring to a controversy over a proposed rewrite of some Black history standards for middle schools in the state. "I went to Florida last July to call out what they were trying to do to replace our history with lies. And apparently there’s a never ending flow of that coming out of that state."

Donalds defended his comments on MSNBC, saying he was not being "nostalgic" about Jim Crow but was trying to make the narrow point about Black marriage rates and a stronger conservative identity.

During the Jim Crow period, he said, "the marriage rates of Black Americans were significantly higher than any other time since then in American history" and that since then, "they have plummeted."

Some Democratic characterizations of Donalds’ remarks were overbroad. But experts told PolitiFact that Donalds’ remarks about Black Americans’ families and conservative identity were thorny in their own right.

Donalds’ office did not respond to an inquiry for this article.

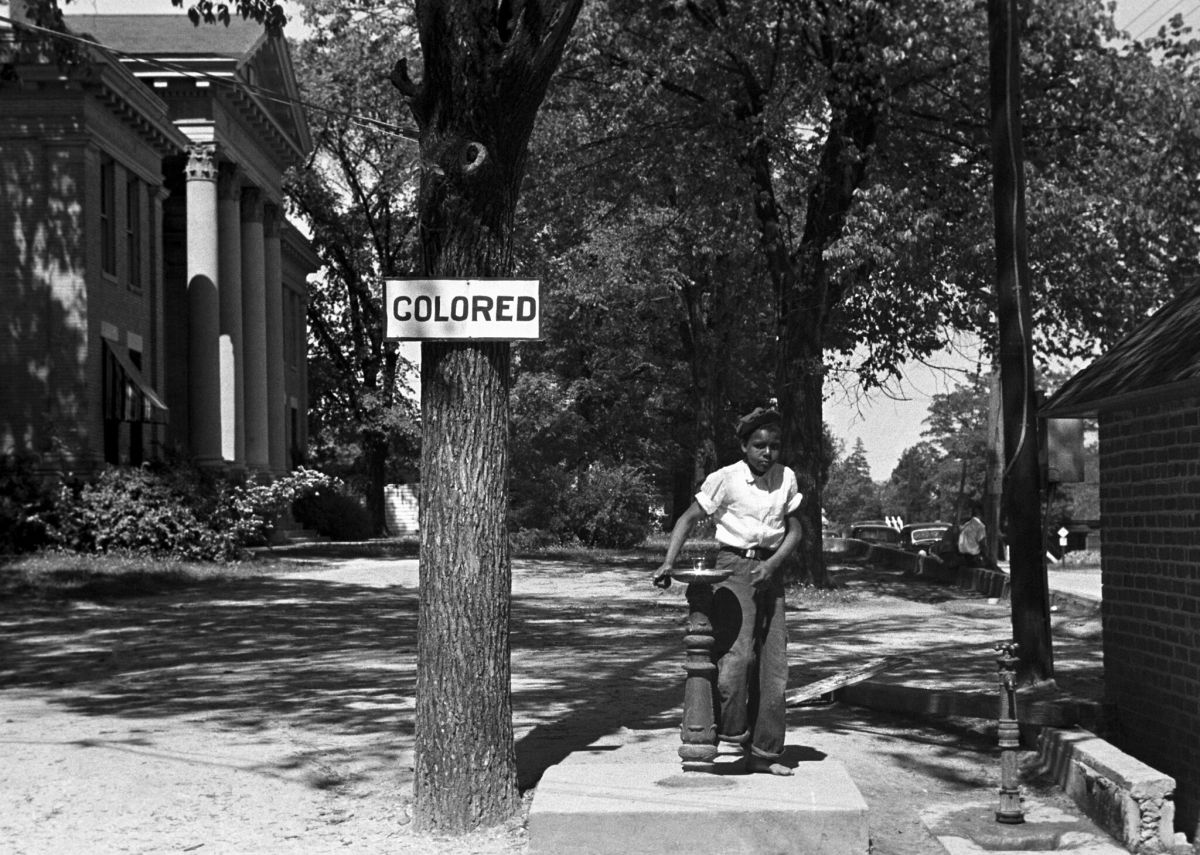

A segregated drinking fountain at the Halifax County Courthouse in North Carolina in April 1938. (Library of Congress, public domain)

Black marriage rates have fallen, but for multiple reasons

There is some statistical evidence to support Donalds’ claim about Black marriage rates being stronger during the Jim Crow era. However, it omits a lot of important context, experts told PolitiFact, including the role of broader social, educational and economic patterns.

The percentage of Black women ages 40 to 44 who were ever married was about 94% in 1930 and remained above 90% through 1970, research by sociologists Kelly Raley of the University of Texas and Megan Sweeney and Danielle Wondra of UCLA shows. Since then, the rate has fallen considerably, to about 63% in 2012.

The pattern for white women has also fallen, but less dramatically, ending up around 88% in 2012, down from nearly 100% in 1930.

The researchers found a similar pattern of rising divorce rates. "Between 1940 and 1980, both white and Black women experienced large increases in divorce, but the increase occurred sooner and more steeply for Black women," they wrote.

Some conservative commentators have argued that government policies, including safety net programs that make it possible for women to try single-parenthood, are a leading cause of fractured families.

However, the presence of other factors makes it hard to pinpoint a single cause for this family fracturing. Raley, Sweeney and Wondra cite such factors as "an enormous decline in unskilled manufacturing jobs during the 1970s and 1980s (that) hit Black men particularly hard" and higher rates of death and incarceration among Black men.

Another factor is the rising status of women and increased female employment. With women, and especially Black women, often ending up with more education than men, the pool of what the authors call "desirable partners" is constrained.

"Donalds ignores the negative impact of poverty on families and the reduction in Black family poverty produced by civil rights enforcement and social welfare programs," said Dorothy E. Roberts, a University of Pennsylvania law and sociology professor. "Surely, Black families would be stronger if the United States had less structural racism, including lower incarceration rates, and more generous social welfare programs."

Black Americans’ political motivations during Jim Crow are difficult to prove

Donalds’ claim that Black people "voted conservatively" during the Jim Crow era is not possible to prove through hard evidence, experts said.

In the South under Jim Crow, "most Black people could not vote," University of Pennsylvania historian Kathleen M. Brown said. There might be voting records for the fraction of Southern Black people who were able to vote during the decades of Jim Crow laws, but this small group would not represent the views of the entire Southern Black population.

Black Americans did vote in the North during the Jim Crow period, but they were not living under Jim Crow’s legal and social strictures.

Historians said a pattern of Black voters backing Republicans during the Jim Crow era would not support the idea that they were "conservative" in the way that today’s Republican Party is.

In the North, Black people "voted for Republicans as the party of Abraham Lincoln who ‘freed the slaves,’" said Mary Frances Berry, a University of Pennsylvania historian whom Democratic President Jimmy Carter named to the U.S. Civil Rights Commission.

Black people in the South would have been likely to vote Republican for the same reason if they’d been able, Harvard University historian Alexander Keyssar said.

The Republican Party in that period "tended to be more conservative" on economic regulation while also being seen as "more sympathetic to Black rights," Keyssar said.

"Conservatism" as a defined ideological movement emerged in the 1950s, late in the Jim Crow period, historians said.

Andra Gillespie, an Emory University political scientist, said Black voters have historically compartmentalized their views, separating what Donalds might consider their "conservative" perspectives on social issues from their more liberal views on racial issues.

Today, Gillespie said, conservative Black people "are more likely to still vote for and identify with the Democratic Party, despite the fact that liberals of other racial groups would be strongly predicted to be Democrats and conservatives of other backgrounds would be strongly predicted to be Republican. This is because of the Democratic Party’s 60-year issue advantage on questions of race and civil rights."

Our Sources

Philadelphia Inquirer, Rep. Byron Donalds draws backlash for expressing nostalgia for Jim Crow era during Philly event, June 5, 2024

NBC, Rep. Byron Donalds defends comments about Jim Crow, June 6, 2024

The Washington Post, When did black Americans start voting so heavily Democratic?, July 7 , 2015

NPR, Why Did Black Voters Flee The Republican Party In The 1960s?, July 14, 2014

Kelly Raley, Megan Sweeney, and Danielle Wondra, "The Growing Racial and Ethnic Divide in U.S. Marriage Patterns" (Future Child), Fall 2015

Email interview with Dorothy E. Roberts, law and sociology professor at the University of Pennsylvania, June 7, 2024

Email interview with Alexander Keyssar, Harvard University historian, June 7, 2024

Email interview with Kathleen M. Brown, University of Pennsylvania historian, June 7, 2024

Email interview with Mary Frances Berry, University of Pennsylvania historian, June 7, 2024

Email interview with Andra Gillespie, Emory University political scientist, June 10, 2024