"Guaranteed health care for all."

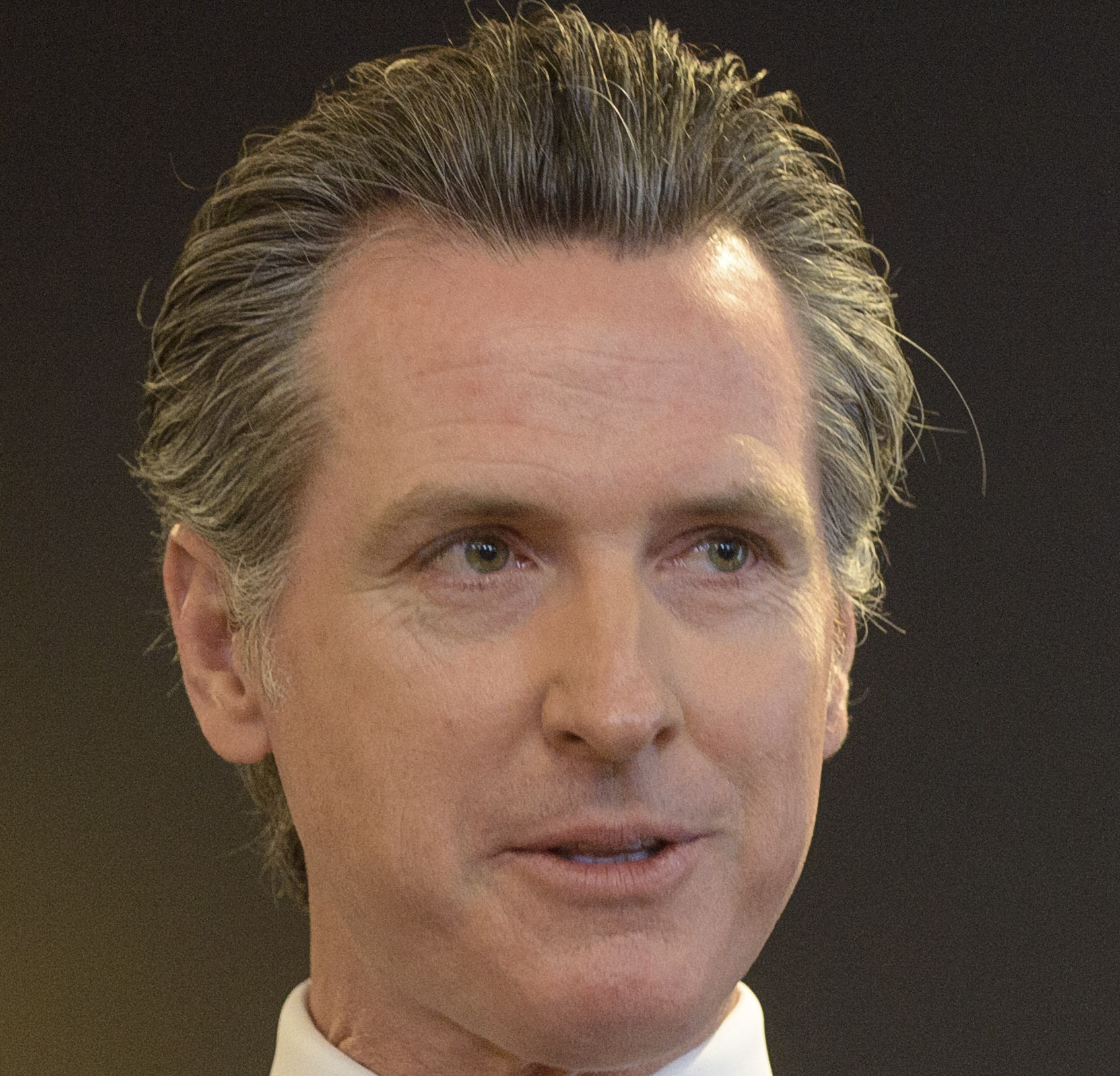

That's the promise Gov. Gavin Newsom made repeatedly on the campaign trail.

Newsom's campaign website was more specific:

"As Governor, he will ensure California residents have universal access to healthcare, regardless of their ability to pay, pre-existing conditions, or immigration status."

Creating a system where all California residents have health coverage and access, also known as universal healthcare, is a tall order.

When the newly-inaugurated Democratic governor unveiled several budget proposals on the topic last week, we decided to examine whether they move his pledge forward on our Newsom-Meter and, if so, by how much.

Here's what we found:

Expanding coverage for undocumented Californians

In his budget, Newsom proposed expanding Medi-Cal coverage to an estimated 138,000 young undocumented adults in the state, ages 19 to 25. That plan would cost a projected $260 million and go into effect in July if approved by the Legislature.

Medi-Cal already covers undocumented children living in the state.

California has greatly expanded health coverage in recent years, reducing its uninsured rate from 17.2 percent in 2013 to a historic low of 7.4 percent in 2016.

But about half of those who remain uninsured are undocumented residents.

"We are approaching universal coverage for people that are eligible for coverage. Without addressing the undocumented issue, you won't get to universal coverage," Peter Lee, executive director of Covered California said on Capital Public Radio's Insight show this week.

Increased subsidies

Newsom's budget would also expand subsidies through Covered California, the state's health exchange, for low- and middle-income residents to enable more people to afford health insurance.

Specifically, the move would apply to households that earn between 400 and 600 percent of the federal poverty level, which was about $25,000 for a family of four last year. A family of four that makes 600 percent of the poverty level earns about $150,000 a year. The subsidies are provided on a sliding income scale.

Funds to pay for the increased subsidies would come from Newsom's plan for a California individual mandate, or penalty imposed for not having health care. The Legislature would need to approve a state mandate.

Congress revoked the Affordable Care Act's individual mandate in 2017, allowing people to opt out of having health insurance without a penalty. Massachusetts, New Jersey, Vermont and the District of Columbia have all passed their own individual mandate laws, while several more states are considering doing the same.

Health policy experts praised Newsom's early plans.

"I think the governor has made some pretty significant progress," said Gerald Kominski, director, UCLA Center for Health Policy Research. "So, I am satisfied that he's moving things forward. He is not going to achieve health care for all with the proposals that he has proposed so far. But he has also said that is a continuing goal and I think what he's done is made a down payment on some significant steps."

Healthcare access

Health policy experts say ensuring Californians can access health care can be as important as providing coverage.

Joy Melnikow, director of the UC Davis Center for Healthcare Policy and Research, said Newsom's budget includes several proposals that could improve access.

Melnikow in an email pointed to pledges in the budget that would "increase the availability of care, including mental health, primary care, family planning services, and dental care," by extending supplemental payments to Medi-Cal providers.

She also cited a proposed $50 million increase that could improve access to mental health care by training more practitioners, along with a $25 million increase that would help mental health professionals better detect and intervene when young people are at high risk of experiencing psychosis.

Single-payer health care

Notably, Newsom's plans do not make progress on creating a single-payer government-run healthcare system, which he identified during his campaign as the best way to pay for universal health care.

That's a separate and more difficult promise we're tracking and we've yet to see clear evidence that it's moving forward.

Rating on universal healthcare pledge

Newsom's budget proposals — to expand Medi-Cal for young undocumented adults and subsidies through Covered California — mark the first concrete steps forward on his promise to create universal healthcare. We'll monitor how far those actions go.

We rate Newsom's pledge 'In the Works.'

In the Works — This indicates the promise has been proposed or is being considered.

How the Newsom-Meter works:

We'll publish updates on Newsom's progress, or lack thereof, on each of 12 campaign pledges. We will rate outcomes, not intentions or proposed solutions, the same standard used for PolitiFact's other promise meters.

Notably, a promise is not a position statement. We will define it as a prospective statement of an action or result that is verifiable. All of the promises will list the source.

The Newsom-Meter has six levels:

Not Yet Rated — Every promise begins at this level and retains this rating until we see evidence of progress — or evidence that it has stalled.

In the Works — This indicates the promise has been proposed or is being considered.

Stalled — There is no movement on the promise, perhaps because of limitations on money, opposition from lawmakers or a shift in priorities.

Compromise — Promises earn this rating when they accomplish substantially less than the official's original statement but when there is still a significant accomplishment that is consistent with the goal.

Promise Kept — Promises earn this rating when the original promise is mostly or completely fulfilled.

Promise Broken – The promise has not been fulfilled. This could occur because of inaction by the executive or lack of support from the legislative branch or other group that was critical to its success. A Promise Broken rating does not necessarily mean that the executive failed to advocate for the policy.

The ratings can change whenever the circumstances change. It's possible that the status could initially go to In the Works, but then move back to Stalled if it's decided the proposal has hit a lull.

PolitiFact has been tracking the promises of presidents, governors and mayors for more than a decade, and no one has achieved everything.