Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

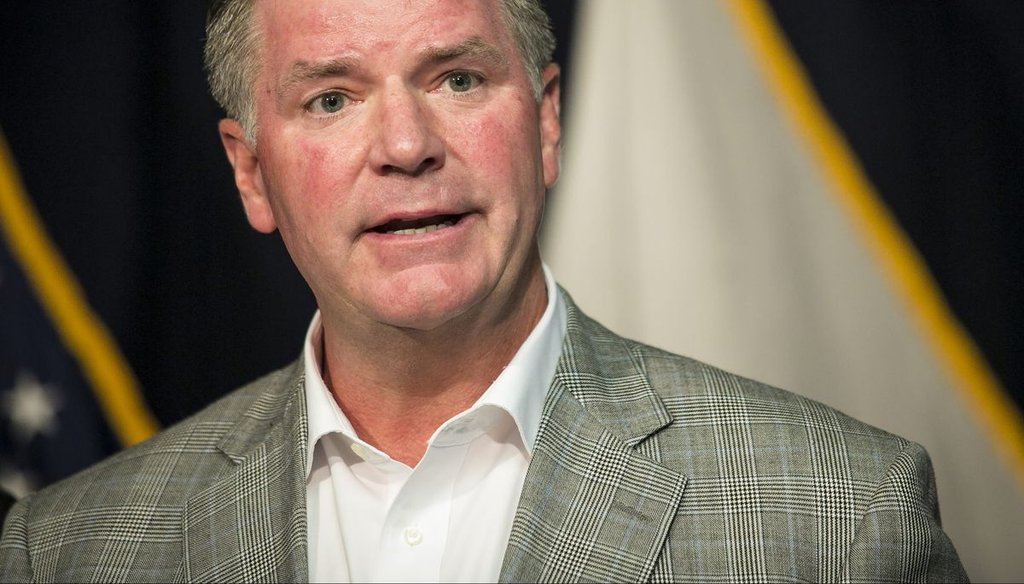

Illinois State Senate Republican Leader Bill Brady. | Ashlee Rezin/Sun-Times

Illinois has had an income tax for 50 years and rates, while bouncing up and down, have always been one-size fits all. That could change next year if voters approve a constitutional amendment to replace the flat tax with a system of graduated rates that charge more to the wealthy.

Democratic Gov. J.B. Pritzker made the switch a centerpiece of his campaign last year, and in the months since he took office we’ve fact-checked a number of assertions from both those who support the switch and those who oppose it.

Another in the series came recently from state Senate Republican Leader Bill Brady of Bloomington in a speech at the City Club of Chicago.

"We stood united as Republicans against this (the graduated tax) primarily because we could find no safeguards for middle-income families," Brady said. "The last income tax increase in the state of Illinois, we saw the largest exodus of middle-income families."

On its face, the claim from Brady was a head scratcher because the most recent hike in the flat income tax, from 3.75 % to 4.95 %, was imposed by the legislature in mid-2017. There’s a lag in the availability of tax data that could illustrate who it is that might be leaving the state, and the latest figures available are from 2016 — prior to that last tax hike.

So what was Brady talking about?

When we reached out to his office, spokesman Jason Gerwig told us Brady meant to reference low-income rather than middle-income families.

By way of support, he pointed us to the Better Government Association’s own recent analysis of federal tax filings between 2006 and 2016, a period that included four years during which the state’s tax rate temporarily rose from 3% to 5%. That investigation found the number of high-income tax filers in Illinois grew robustly after the tax hike even though critics had warned at the time that wealthier taxpayers would flee the state, while the number of low-income tax filers shrank.

But PolitiFact rates claims based on the words people speak. Corrections by his staff aside, Brady not only referred to the state’s most recent tax increase and not the 2011 hike but also twice mentioned middle-income families in his remarks.

Given that there is not yet data to shed light on the changing makeup of taxpayers following the 2017 increase, however, we also decided to assess how middle-income earners fared during the previous hike.

There is no official definition for "middle class," so we looked at several groups that might appear to fit that description, depending on the number of people in their families and the cost of living where they reside.

The IRS data that was the focus of the BGA analysis shows that the number of filers reporting adjusted gross income between $50,000 and $100,000 grew slightly during the four years that earlier tax hike remained in effect. Growth was even greater among those reporting incomes of between $100,000 and $200,000, roughly approximating what might be considered upper middle class.

In fact, the only income group that shrank in size was the one comprised of filers reporting annual income below $50,000. So Brady would have been on slightly firmer ground had he actually said what Gerwig said he intended to. At that, however, the numbers apply not to the last Illinois tax increase but the second to the last.

Gerwig predicted the slide continued after the 2017 tax hike, but he had no data to back that up because it doesn’t yet exist.

In his speech, Brady also sought to make the argument that a graduated tax would inevitably impose financial pain on middle-income earners by citing a past instance when the flat tax did just that. A key flaw in that claim is that Democratic lawmakers and Pritzker have OK’d a rate structure contingent on the passage of the constitutional amendment that would only hike taxes on those with incomes of $250,000 or more.

Republicans, including Brady, caution those rates amount to little more than an opening bid and provide no assurance that Democrats won’t later hike rates more on everyone. While it’s true there’s nothing to prevent that, there’s also nothing to prevent it under the current flat tax system, as the very examples Brady seized on underscore.

More broadly, a link between state populations and tax policy changes is far from clear.

In an interview with the BGA for its analysis of the 2011 tax increase, economist Michael Hicks of Ball State University said that people make decisions about when and where to move the "same way they look for value in the purchase of food, clothing or other items."

"The amenities that seem to matter most are good schools or school choice, thick labor markets, neighbors who are high income, and more highly educated, and other things that are often associated with cities or suburbs in large metro places," said Hicks, who specializes in the effects of public policy on economic activity. "All things being equal, a higher tax will cause some people to leave, but all things aren’t equal."

While arguing against a Democratic plan to swap out Illinois’ flat income tax for a series of graduated rates, Brady said the last time the state increased its income tax, "we saw the largest exodus of middle-income families."

Illinois last hiked its income tax in 2017 and data is not yet available for any year later than 2016, so there’s no way to assess how many middle-income Illinoisans have filed taxes in the state since it took effect.

Brady’s office told us the senator meant to refer to low-income families, whose share of tax filings did decrease following the state’s second-to-last tax hike, IRS data show, while the returns from all other income groups grew.

But that’s not what Brady said in his City Club speech, so we rate his claim False.

FALSE — The statement is not accurate.

Click here for more on the six PolitiFact ratings and how we select facts to check.

Video: Senate Republican Leader Bill Brady, City Club of Chicago, June 18, 2019

Email interview: Jason Gerwig, Brady spokesman, June 20, 2019

"Poor Left, Rich Thrived When Illinois Hiked Flat Tax," Better Government Association, April 8, 2019

IRS Statistics of Income, 2010-2014

Phone and email interview: Daniel Kay Hertz, research director at the Center for Tax and Budget Accountability, June 20, 2019

In a world of wild talk and fake news, help us stand up for the facts.