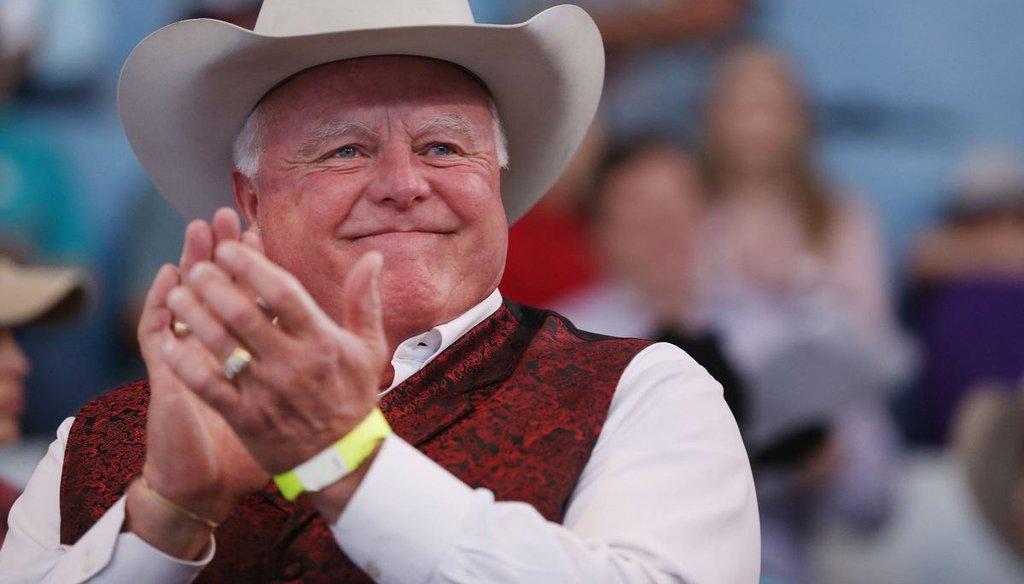

The post, shared to an Erath County Facebook group, was shared more than 2,000 times and garnered dozens of comments — including one from the state’s agriculture commissioner. "Who told them to leave?" Miller wrote. "Get a rope."

After people expressed outrage at his remark, Miller edited the comment and added: "Good grief people, it’s a joke, an old saying from a Pace Picante commercial. Lighten up."

"I guess the young leftists at the Texas Tribune have never heard or watched the Pace Salsa commercial. I would also bet that they are not aware that Confederate veterans were conferred with many of the same benefits of other United States military veterans by Acts of Congress back in 1929 and 1957. Sad, that on a day in which we should honor all of our veterans, including those who fought in the Civil War, there are some who, instead, wish to sow discord and discontent."

Instead, Miller’s statement focuses on two pieces of legislation approved by Congress long after the end of the Civil War. One required the federal government to place headstones or markers on the graves of Confederate soldiers. The other allowed veterans and their widows to collect a federal pension.

Todd Smith, a spokesman for Miller, pointed to these pieces of legislation and emphasized that Miller did not go so far as to say Confederate veterans were designated as U.S. veterans.

"In his post, Commissioner Miller did not state that Confederate veterans had been conferred U.S. veteran status," Smith said. "Instead, he said that ‘Confederate veterans were conferred with many of the same benefits of other United States military veterans by Acts of Congress…’ So, these two laws appear to provide benefits to CSA veterans EXACTLY AS IF they had been a U.S. military service member."

Post Civil War: No federal benefits

At the close of the Civil War, government assistance for Union veterans and Confederate veterans was handled very differently.

In the South, state and county governments were the primary vehicles for offering aid to Confederate veterans and their families, according to Susanah Ural, a professor of history at the University of Southern Mississippi, where she also serves as co-director of the Dale Center for the Study of War and Society.

"It became a huge issue, because a lot of families had been promised that if the man left or was injured, we’ll make sure the family is taken care of," Ural said, noting that states had to allocate significant funds to the effort, considering the high number of fatalities and the families left behind.

Union soldiers and widows received a pension from the federal government and were able to obtain care from federally-run hospitals and homes.

Confederate veterans could not.

"The federal government was never paying Confederate pensions at that point," Ural said. "You took up arms against the federal government, so they’re not going to do that."

There were also differences when it came to burial. National cemeteries were originally created to honor Union soldiers, according to

the National Park Service.

Confederate veterans could not be buried in these cemeteries, with some exceptions. Soldiers captured as prisoners of war were buried in designated sections within the cemeteries.

In 1929: Headstones approved for Confederate graves

In 1906, the federal government authorized the placement of headstones for Confederate soldiers who were buried in national cemeteries — a small percentage of all those who died.

It was not until 1929 that Congress authorized Confederate soldiers buried in unmarked graves anywhere to receive — when requested — "appropriate Government headstones or markers at the expense of the United States."

In 1958: Federal pensions for veterans, widows

By the time Congress authorized federal pensions for Confederate veterans and their widows, the Spanish-American War, World War I and World War II had come to pass.

It was 1958 (Miller got the year wrong) and the country was in the throws of the Cold War, prompting a wave of reconciliation internally.

"They made a very big deal about the last surviving veterans on both sides," said Barbara Gannon, an associate history professor at the University of Central Florida who specializes in the Civil War and military history. "It was about saying: ‘We’re all real Americans, as opposed to Communists’."

Also at this point, the last surviving verified Confederate veteran had died. Pleasant Crump died in 1951 at the age of 104, according to the

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Another man purporting to be a Confederate veteran was still alive, but his status is disputed. He died in 1959.

News reports from 1958 said there were an estimated 1,500 widows of Confederate soldiers who were still alive and could potentially qualify for the pension.

The last surviving Confederate widow was Maudie Hopkins, who died in 2008 at the age of 93, according to the VA. But Hopkins did not receive pension benefits after her husband’s death, according to her obituary in the

Seattle Times.

The law stated that the Veterans Administration "shall pay to each person who served in the military or naval forces of the Confederate States of America during the Civil War a monthly pension in the same amounts and subject to the same conditions as would have been applicable to such person ... if his service in such forces had been service in the military or naval service of the United States."

But there were no surviving veterans to take advantage of this benefit.

"It is reasonable to assert that no portion of federal aid ever went to the care of a single Confederate veteran," reads an article published on the website for "The Journal of the Civil War Era" exploring care offered to veterans after the war.

Even though there were no surviving veterans who claimed the pension offered by the 1958 legislation, Gannon said the effort was more about the push for reconciliation.

"These were gestures, but they were important gestures to southerners," she said.

In

a March 1958 column by George Dixon, published in The Evening Independent, then-Sen. Russell Long of Louisiana argued the same point: "Wouldn’t you think Uncle Sam could afford to make one generous gesture after a hundred years?"

Miller said: "Confederate veterans were conferred with many of the same benefits of other United States military veterans by Acts of Congress back in 1929 and 1957."

It is clear that, in the wake of the Civil War, Congress did not grant Confederate veterans the same benefits as other U.S. veterans. Their pensions were doled out by state governments, they were unable to seek treatment from federal veteran’s hospitals, and they were not considered U.S. military veterans.

That started to shift in 1929, when Congress authorized the placement of federal headstones and markers on the graves of Confederate veterans, including those outside of national cemeteries.

When Congress decided to take over administration of pensions to Confederate veterans and their widows in 1958, only one veteran who may have qualified was still alive (his status as a Confederate veteran is disputed by historians).

Miller is right that Congress eventually afforded Confederate veterans many of the benefits awarded to other U.S. military veterans, but no qualifying veteran ever actually received aid from the federal government (outside the placement of headstones).

We rate this claim Mostly True.

MOSTLY TRUE – The statement is accurate but needs clarification or additional information