Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

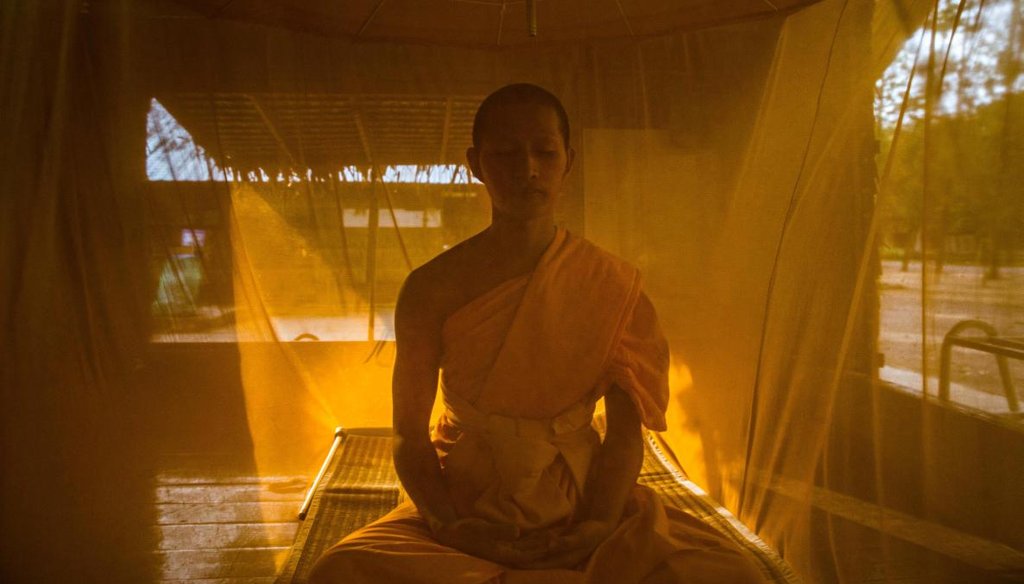

A novice monk takes part in evening meditation, under his mosquito net, in the monastery within Wat Dhammakaya in Bangkok, Dec. 12, 2016. (Lauren DeCicca/The New York Times)

In a rural town 175 miles west of the Indian Ocean, a group of young researchers are pitting their wits against a new twist in an ancient disease.

Mosquitoes that carry the malaria parasite are adapting to a highly successful weapon used against them, and the shift has scientists racing to keep up.

The struggle goes beyond the fight against malaria, a disease that infects about 200 million people each year. It has implications for fighting viruses like Zika and others we haven’t heard about yet.

Arnold Mmbando, a 29-year-old Tanzanian biotechnology specialist at the Ifakara Health Institute, enters a high-ceiling wood frame structure researchers call the "vectorsphere." It includes a full-size mock hut, complete with a garden.

"No wild mosquitoes can get in here," Mmbando says. "The only mosquitoes here are the ones we raise ourselves."

Sign up for PolitiFact texts

Nearby, a black wooden box about two feet on a side sits in front of the hut’s door. Louvers on the sides open to the air. While it looks different, many Americans would recognize the black box’s function. It’s a solar powered bug zapper. Inside, a metal mesh is wired to a small solar cell on the lid. The box is baited with a concoction that smells like a human to the bugs.

"This is locally made here by local carpenters," Mmbando says. "We only imported this solar panel because that’s the one thing we can’t make here."

Another researcher, John Paliga Masalu, enters with a burlap mat inside a metal frame. It’s made from Tanzanian grown fiber and saturated with insect repellant. Masalu plops down in a chair by the hut and props the mat by his side.

On its own, the mat creates a protective zone several meters across. When paired with the bug zapper, it produces a lethal one-two punch, the researchers say. The mosquitoes flee from the mat and into the electric mesh.

Malaria is a palpable threat for both these men. The disease is treatable, but when the parasite goes unchecked in the body, it often turns deadly. It can attack the brain, the lungs and destroy the red blood cells that carry oxygen. Infants and young children are particularly vulnerable.

"I see a lot of people being killed by this disease since I was young," Mmbando said.

These two bootstrap innovations have one thing in common: they target the bugs that bite outside. Until recently, the threat here came almost entirely from late night indoor biting bugs. But in the search for a blood meal, the mosquitoes are showing up at different times and places. It has made the fight against malaria more complicated than ever.

A maverick in Ifakara

The latest riddle comes at a moment when worldwide malaria deaths have plummeted 50 percent. By everyone’s estimate, a huge chunk of the credit goes to the massive distribution of long-lasting, insecticide-treated nets, which not only stop a mosquito but kill the bug so it can’t find another victim.

Insecticide-treated net distribution skyrocketed in the early 2000s. Between 2013 and 2015 alone, half a billion nets were sent to sub-Saharan Africa.

"It is truly our key tool," said Pedro Alonso, director of the World Health Organization’s Global Malaria Program.

Not everyone is completely on board. Fredros Okumu, the Ifakara Health Institute’s research director, says mosquitoes are becoming resistant to the insecticides on bed nets. His solution: Take out the chemicals.

"We have argued, what we need is a long-lasting, durable bed net not necessarily with insecticide," Okuma said. "A bed net, as long as it’s durable, will give you the same value."

In malaria circles, that could qualify as apostasy. And truth be told, it runs counter to certain studies. Entomologist Hilary Ranson at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine said while insecticide resistance has spread rapidly, even a resistant bug pays a price when it hits a treated net.

"We’ve seen that a mosquito’s lifespan is reduced by half even if it isn’t killed," Ranson said.

Okumu is far from a total outsider. He co-chairs a WHO group on vector control, and he’s seen his unorthodox view shot down before. He is undeterred. From his vantage point in Ifakara, he has seen how treated nets fall short.

A shifting battleground

About five years ago, the team in Ifakara saw that the bugs were wising up.

The institute traps and collects mosquitoes throughout the river valley. In their labs, technicians deftly pick the bugs apart with tweezers and run their tissue through DNA scanners. In 2011, a strange result became crystal clear. The species that once devastated this valley, Anopheles gambiae, had virtually disappeared.

"This thing didn’t collapse gradually, it just plummeted," Okumu said.

As one species went away, two others -- arabiensis and funestus -- rose up to replace it. Neither spreads malaria as well as gambiae, but both share two disturbing qualities. They are resistant to the insecticide in bed nets, and they bite outside or before many people get under a net to sleep.

Okumu, along with many others, believes the nets are at least partially to blame. In the mid 2000s, nearly every household in the valley got one.

"With the wide coverage of bed nets, the mosquitoes changed," Okumu said. "The mosquitoes know that human beings are more available outside the house than inside. Primarily because people are using bed nets."

With both biting habits and resistance, the root of the problem is only a single family of chemicals has been found both safe and effective to use on the nets.

Nick Hamon, the CEO of the Innovative Vector Control Consortium, which works to create new insecticides, said the reliance on a single chemical class, in this case pyrethroids, and a single device, the nets, has had an inevitable result.

"If you use a monotherapy, you will get resistance," Hamon said. "Particularly in the insect world where they can be reproducing every 12 to 15 days."

When you’ve got billions of mosquitoes, with any single attack on the bugs, the mix of mutation and adaptation keep victory just out of reach.

Few good choices

The link between nets and resistance has produced a steady drip-drip-drip of research questioning whether this essential tool will retain its punch. (Indoor spraying is another but less widely used tactic.)

A 2016 article in the British medical journal Lancet carried the ominous title "Averting a malaria disaster: Will insecticide resistance derail malaria control?"

Everyone faces the same conundrum: There’s nothing comparable to replace the nets. Yet, the more you use them, the greater the pressure on the mosquitoes to adapt.

In response to conflicting research, the World Health Organization and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, which helps support PolitiFact, funded a five-year, five-nation study. Comparing zones of high and low insecticide resistance, the study aimed to resolve whether bed nets remained effective.

At the 2016 gathering of the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene in Atlanta, scientists from five continents filled a hotel ballroom to hear the results. They heard good news. Even in the face of resistance, the nets "still provide significant protection from malaria-carrying mosquitoes."

But rather than a collective sigh of relief, challenges quickly came from the floor. Critics from some of the top research centers pointed to fundamental flaws in the study’s methods. Christen Fornadel, an entomologist with the U.S. President’s Malaria Initiative, suggested the study’s numbers hardly merited any rosy conclusions.

Fornadel’s comment centered on the nets’ original value of killing mosquitoes, not just protecting the person under one. "If you look at some of your results, community protection from the nets is being lost," Fornadel said.

In a typically staid forum, Fornadel drew applause from the floor from others who had seen the same thing.

Running against the clock

Still, even as they left the hotel ballroom, the most ardent critics saw no good alternative.

And in an interview, WHO’s Alonso painted a complicated picture. Alonso said nets have always had their limits. The right response is to come up with new tactics from places like Ifakara.

"Do we understand that resistance is extending and is becoming a biological threat? Sure," he said. "Does that further contribute to the urgency to develop new tools? Absolutely."

Right now, the push is to develop at least three completely new kinds of insecticides.

"You have to come up with several so you can rotate them and avoid recreating the resistance problem," Hamon said.

Importantly, that applies just as much to the mosquitoes that carry Zika as to the ones that spread malaria. (One key difference -- the Zika mosquitoes are daytime biters and bed nets offer little protection. Still, killing them with insecticides is a key weapon.)

Even the most optimistic delivery date for Hamon’s work is about five years off and meanwhile, costs are expected to rise as government and aid groups tweak the chemical cocktail to squeeze a little more life out of the nets.

A big question is how Washington and President-elect Donald Trump respond to the bigger price tag. America provides about 35 percent of the global malaria budget.

Working under the shadow of history

The world has been here before. In 1955, the community of nations vowed to end malaria. "It’s simply a matter of going out to do it," the head of WHO said back then. By 1969, it was clear there was nothing simple at all with this disease. The program shut down and malaria surged back.

The episode is a touchstone for the WHO’s Alonso.

"We just have to recognize that we are in for a very long run," Alonso said. "Malaria is hard. It’s super hard. And we will face unexpected challenges all the way to eradication."

The WHO’s latest world malaria report contains a hint of new headwinds: For the first time this decade, the number of malaria cases in 2015 failed to drop.

Back in Ifakara, 68-year-old rice farmer Lucas Ndumbali has seen the gains and the limits in the fight against malaria. He’s lived long enough to see his friends no longer dying from the disease. Every night, Ndumbali and his family sleep under a chemically treated net.

But as we talked, Ndumbali called over his 6-year-old son, Method. A few days earlier, Method had been diagnosed and treated for malaria.

His father said he must have caught it outside.

Our Sources

Interviews:

Pedro Alonso, director, Global Malaria Program, World Health Organization

Nick Hamon, CEO, Innovative Vector Control Consortium

Hilary Ranson, professor of medical entomology, Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine

Lisa Reimer, lecturer of entomology, Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine

Ifakara Health Institute: Fredros Okumu, John Paliga Masalu, Arnold Mmbando, Alex Limwagu, Gerry Killeen, and others

USAID - President’s Malaria Initiative: Entomologists Laura Norris and Christen Fornadel, and public health advisor Megan Fotheringham

John Gimnig, research entomologist, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Ally Mohamed, program manager, National Malaria Control Programme, United Republic of Tanzania

Elizabeth Ivanovich, senior officer of global health, United Nations Foundation

Jennifer Kates, director, Global Health and HIV Policy, Kaiser Family Foundation

Email interviews:

Greg Lanzaro, professor, Department of Pathology, Microbiology and Immunology, University of California - Davis

Maureen Coetzee, professor of Medical Entomology, University of the Witwatersrand

Articles:

World Health Organization, World Malaria Report 2016 Dec. 13, 2016,

eLife, Coverage and system efficiencies of insecticide-treated nets in Africa from 2000 to 2017, December 29, 2015

Nature, The effect of malaria control on Plasmodium faliciparum in Africa between 2000 and 2015, Oct. 8, 2015

Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine, Current and future prospects for preventing malaria transmission via the use of insecticides, 2016

Malaria Journal, Implementation of the global plan for insecticide resistance management in malaria vectors, April 2015

PLOS Medicine, Reducing Plasmodium falciparum Malaria Transmission in Africa: A Model-Based Evaluation of Intervention Strategies, Aug. 10, 2010

Lancet, Averting a malaria disaster: will insecticide resistance derail malaria control?, Feb. 12, 2016

Malaria Journal, The effectiveness of a nationwide universal coverage campaign of insecticide-treated bed nets on childhood malaria in Malawi, Oct. 18, 2016

Malaria Journal, Design of a study to determine the impact of insecticide resistance on malaria vector control: a multi-country investigation, July 22, 2015

Malaria Journal, Outdoor-sleeping and other night-time activities in northern Ghana: implications for residual transmission and malaria prevention, Jan. 28, 2015

PNAS, Adaptive introgression in an African malaria mosquito coincident with the increased usage of insecticide-treated bed nets, Jan. 20, 2015

Malaria Journal, Increased proportions of outdoor feeding among residual malaria vector populations following increased use of insecticide-treated nets in rural Tanzania, April 9, 2011

Emerging Infectious Diseases: CDC, Increased Pyrethroid Resistance in Malaria Vectors and Decreased Bed Net Effectiveness, Burkina Faso, October 2014

Lancet, Malaria morbidity and pyrethroid resistance after the introduction of insecticide-treated bednets and artemisinin-based combination therapies: a longitudinal study, Aug. 18, 2011

World Health Organization, Implications of insecticide resistance for malaria vector control, November 2016

Rice farmers and their families often live in elevated huts near the rice paddies, a prime mosquito breeding zone. (Jon Greenberg)

Rice farmers and their families often live in elevated huts near the rice paddies, a prime mosquito breeding zone. (Jon Greenberg) Insecticide resistance has spread across sub-Saharan Africa since 2000 and threatens malaria control efforts. The extent is greater than the map reveals (red=confirmed/yellow=suspected) because many areas go untested. (IRMapper.com/Allsion Graves)

Insecticide resistance has spread across sub-Saharan Africa since 2000 and threatens malaria control efforts. The extent is greater than the map reveals (red=confirmed/yellow=suspected) because many areas go untested. (IRMapper.com/Allsion Graves) In this Tuesday, April 7, 2015, file photo, Meghu Tanti, left, a health assistant collects blood samples from an elderly woman thought to have malaria on the outskirts of Gauhati, India. (AP Photo/Anupam Nath)

In this Tuesday, April 7, 2015, file photo, Meghu Tanti, left, a health assistant collects blood samples from an elderly woman thought to have malaria on the outskirts of Gauhati, India. (AP Photo/Anupam Nath) Method (Jon Greenberg)

Method (Jon Greenberg)