Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

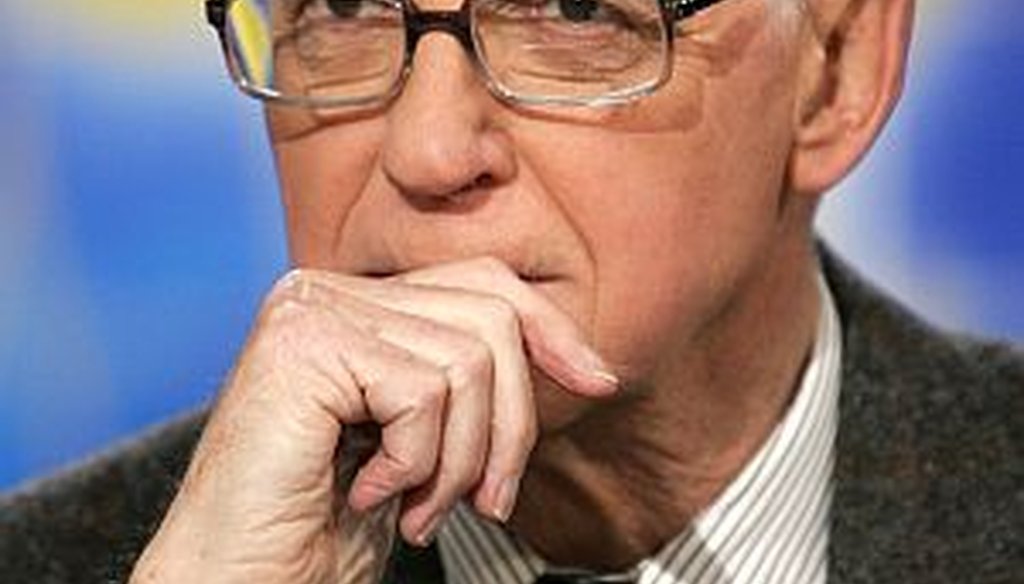

David Broder's columns in the late 1980s sparked more political fact-checking.

David Broder, a Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist and reporter with the Washington Post, died this week. Our colleagues in political journalism have published many tributes to him recognizing his reputation for fairness, his work ethic and his talent for explanatory journalism. We'd like to recognize the important role he played in sparking more political fact-checking.

In the late 1980s, Broder concluded that American journalists needed to do more to hold politicians accountable for their words. The 1988 election, between President George H.W. Bush and Massachusetts Gov. Michael Dukakis, seemed to particularly raise his ire.

"It’s the start of another political year, and the question that demands an answer is: Will the 1990 campaign serve the voters or sicken them?" Broder wrote in one of a series of columns over the years that encouraged more fact-checking by journalists. "The last mid-term election in 1986 and the presidential campaign of 1988 left a bad taste in people's mouths, not because of who won what but because so many of the winning candidates in both parties force-fed a garbage diet of negative TV ads down the country's throat."

Broder said journalists should aggressively question candidates on substantive issues, hold political consultants accountable for the ads they create, and alert the public to attacks that were inaccurate.

He said that when journalists report on political ads, they should demand supporting evidence from campaigns, get rebuttals from the opponent, and then "investigate the situation enough ourselves that we can tell the reader what is factual and what is destructive fiction."

Journalists, he said, had an obligation to check the facts. "The consultants have become increasingly sophisticated about insinuating -- visually or verbally -- charges that they avoid making in literal terms," he wrote. "We have to counter that sophistication by becoming increasingly blunt when we are exposing such falsities."

Broder celebrated fact-checking from around the country to encourage journalists to do more of it. Readers sent him examples of fact-checking journalism from their local newspapers, which Broder highlighted in his column.

By the fall of 1990, newspapers were running ad checks as a regular part of campaign coverage.

The Los Angeles Times noted the trend in a front-page story by Thomas Rosenstiel. The trend meant that TV commercials were now an important part of the national agenda, and that reporters had decided to become "less of a color commentator up in the booth and more of a referee on the field in the hope of cleaning up the game."

NPR's Mark Stencel, who worked for Broder as a researcher in the early 1990s, said in a column this week that Broder not only sparked more fact-checking by the Post, but that his legacy can be seen in FactCheck.org and PolitiFact.

"David instinctively understood how journalism needed to evolve to remain relevant to the voters whose mood he studied so carefully," Stencel wrote. "Now it's up to the rest of us in the news biz to make sure that all he taught us about covering American politics outlives him."

Our Sources

Washington Post, Should News Media Police the Accuracy of Ads?, by David S. Broder, Jan. 19, 1989, accessed via Nexis

Washington Post, Politicians, Advisers Agonize Over Negative Campaigning; Success of Tactics Discourages Policing, by David S. Broder, Jan. 19, 1989, accessed via Nexis

Washington Post, Five Ways To Put Some Sanity Back In Elections, by David S. Broder, Jan. 14, 1990, accessed via Nexis

Washington Post, Put Sanity Back Into Our Elections, by David S. Broder, Feb. 25, 1990, accessed via Nexis

Washington Post, Sick of Issueless Campaigns, by David S. Broder, March 28, 1990, accessed via Nexis

Los Angeles Times, Policing Political TV Ads, Oct. 4, 1990

NPR, Broder's Shift Key: An Unlikely Online Makeover, March 10, 2011