Get PolitiFact in your inbox.

All eyes in Washington have turned toward tax policy after the failure by Congress to replace the Affordable Care Act this summer.

President Donald Trump is pressuring Congress to immediately pass adjustments to the tax code and score a major legislative accomplishment for Republicans this fall.

"With Irma and Harvey devastation, Tax Cuts and Tax Reform is needed more than ever before. Go Congress, go!" Trump tweeted on Sept. 13.

If you want to know with certainty how the proposed changes would affect your tax bill, you're out of luck for now: Policy specifics and guidance from the White House have been sparse.

Little has been announced since the administration released a one-page memo five months ago that teased some of the elements that the administration would like to see in a tax bill.

They included reducing the number of brackets from seven to three; lowering individual rates, including a cut in the top rate from 39.6 percent to 35 percent; setting the corporate tax rate at 15 percent; repealing the alternative minimum tax and the estate tax; repealing a 3.8 percent surtax under the Affordable Care Act; eliminating certain narrow tax breaks while keeping the mortgage-interest and charitable deduction; and changing how companies are taxed on overseas earnings.

With input from experts, here's our guide to some of the key policy fights and how they might affect your bottom line.

Will the bill’s reductions in revenue be fully offset by new revenue streams?

The Urban Institute-Brookings Institution Tax Policy Center has analyzed what a Trump-style tax bill might look like. (The center acknowledges that the White House's scant details makes it subject to change.) They found that it could reduce federal revenues by as much as $7.8 trillion over the next decade. A bit over half of that revenue loss could be reduced if other taxes are raised in their place. Still, the center’s best-case scenario was that revenues would fall by $3.5 trillion over the decade.

Tax policy veterans aren’t optimistic that lawmakers will be able to stomach raising taxes enough, or keeping spending sufficiently in check, to make the numbers even out.

Dan Mitchell, a conservative economist, has written that it's "relatively simple to have a big tax cut and still achieve balance in 10 years with a bit of extra spending discipline. That’s the good news. The bad news is that there’s very little appetite for spending restraint in the White House or Capitol Hill, and this may hinder passage of a tax plan."

Meanwhile, Scott Greenberg, a senior analyst at the Tax Foundation, added that once the list of tax breaks on the chopping block is released, the real lobbying will begin. "Everyone will descend like vultures," he said.

The corporate tax rate

Currently, the United States has among the highest corporate tax rates of any country, at 35 percent. However, commonly used deductions and exemptions enable most corporations to pay a far lower "effective" rate.

Trump is seeking a 15 percent corporate tax rate, but House Speaker Paul Ryan, R-Wis., indicated in an interview with the New York Times that the average rate for industrialized countries -- 22.5 percent -- is a more reasonable goal.

"Where it ends up depends on how many current tax breaks combatants are willing to trim or eliminate" in order to keep the deficit from ballooning, said Roberton Williams, a fellow at the Urban Institute-Brookings Institution Tax Policy Center.

There is disagreement over how much ordinary Americans would benefit from seeing corporate tax rates lowered.

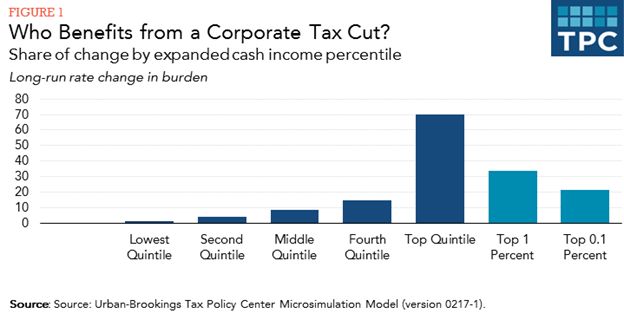

On Sept. 3, Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin told Fox News in an interview that "most economists believe that over 70 percent of corporate taxes are paid for by the workers." However, the Congressional Budget Office and Joint Committee on Taxation put the percentage much lower, at 25 percent. The Tax Policy Center uses an even lower estimate of 20 percent.

Using this lower figure, the Tax Policy Center estimated how different income groups would benefit from a corporate tax cut. The top one-fifth of taxpayers were by far the best positioned.

International taxation

Currently, the United States uses a "worldwide" taxation system to determine whether overseas profits by U.S. based companies owe taxes.

Under this system, a U.S.-based company that earned income in a foreign country with a 20 percent corporate tax rate would pay that 20 percent tax immediately, then pay the difference with the U.S. rate when -- or if -- that money is brought back to the United States. In this example, that income would be taxed at an additional 15 percent if it was brought home to the United States.

The alternative, which could be part of a tax bill, would be to institute a "territorial" system. Under that system, the United States would not charge any additional taxes on overseas corporate income once taxes had been paid in the foreign country. There might also be a one-time opportunity for companies to bring overseas income back to the United States tax-free.

Some favor such a change on philosophical grounds, saying it’s inappropriate for the United States to tax income earned elsewhere. But there’s also a practical argument in favor of a territorial system -- it could encourage U.S. companies to spend money that’s currently parked or invested overseas on facilities or workers in the United States.

The downside is that the country would have to give up the tax revenue it currently receives from overseas income, forcing those shortfalls to be made up elsewhere. A broader concern is that it can be hard to know what portion of a company’s income is earned in the U.S. and overseas, Greenberg said. "If you have clever enough accounting, you can game the system," he said.

Deductibility for businesses

Generally, when an interest payment is made, the payer gets to deduct it and the receiver pays tax on it. But there are some exceptions, and these exceptions can leave some interest flows entirely untaxed, Greenberg said. These untaxed or lightly taxed flows are attractive to policymakers looking for revenue streams to offset tax cuts elsewhere.

However, these exceptions can be hugely important to specific industries, and those industries will fight to keep them. This could drive a wedge between industries that tend to borrow heavily, such as finance and real estate, and those that don’t.

Another deductibility issue affecting businesses is expensing. Today, not all investments can be immediately deducted from taxes; some need to be spread over a number of years, a process called depreciation or amortization. Some lawmakers would like to encourage business investment by allowing immediate expensing for a wider variety of investments.

But as with the tax treatment of interest, different types of companies are affected differently by the rules on expensing. Companies that wouldn’t benefit much from changing the expensing rules, including many established businesses, might rather see a general rate cut. How the tax bill approaches this issue becomes "a huge policy question," Greenberg said.

Individual income tax rates

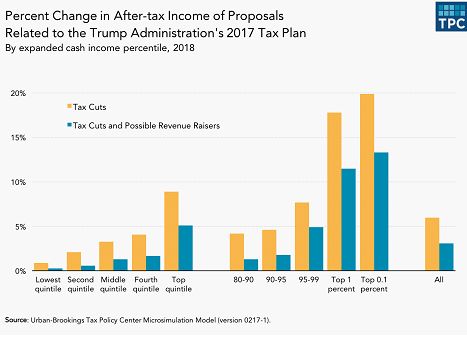

Trump’s memo on taxes emphasized that he wants to decrease the tax burden on the middle class. But the Tax Policy Center analysis suggests that the benefits could tilt heavily toward the wealthy. The center found that a Trump-like tax plan "would be highly regressive" -- that is, it would benefit richer Americans significantly more than those of more modest means.

Looking just at the impact of the tax cuts alone -- and ignoring any tax increases designed to offset the revenue losses -- the center estimated that households that make $50,000 to $86,000 would see their after-tax income increase by about $1,900, or roughly 3 percent. By contrast, the top 1 percent, making more than $732,000 annually, would see a tax cut of $270,000, or almost 18 percent. All in all, 40 percent of the benefits would go to the top 1 percent. Here’s a summary of the center’s findings:

A tilt toward the rich could be a political problem for backers of the bill, Mitchell wrote.

"Even though the rich already pay most of the taxes and even though the rest of us will benefit from faster growth, Republicans are sensitive to that line of attack," Mitchell wrote. "So they will want to include some sort of provision designed for the middle class, but that will have major revenue implications and complicate the effort to achieve revenue neutrality," or no net revenue loss.

One potential compromise, said Williams of the Tax Policy Center, could be to include Trump’s three proposed rates -- 10, 25 and 35 percent -- and then add on a fourth rate at the higher end, perhaps the current 39.6 percent top rate.

A related issue: How business income is treated on individual tax returns.

While many companies pay corporate taxes, others are taxed at the personal income rate of their owner. Today, the top tax rate for such businesses is the top individual rate -- 39.6 percent -- possibly with a few additional percentage points on top, due to the self-employment tax or other levies.

Some lawmakers want to cap the rate for businesses being taxed through individual returns. However, this risks opening up opportunities for tax avoidance, depending on how the taxpayer categorizes certain types of income. The way the rules are written, and how low the cap is set, will be critical, Greenberg said.

Finally, Trump has floated the possibility of changing the tax treatment of carried interest, a kind of income common among hedge fund managers. Currently, such income is taxed at the lower, capital gains tax rate instead of the regular individual income tax rate. Determining the future of carried interest "could become a major stumbling block" in negotiations, Mitchell said.

Itemized deductions

Trump has said he’s open to eliminating a wide range of deductions, except for those affecting mortgage interest and charitable donations. Democrats generally agree with saving those two carve-outs, although Williams said a possible compromise could involve keeping, but capping the amount of, the mortgage-interest deduction.

The deduction for state and local taxes could become a focal point for negotiations. While any change would affect taxpayers of all stripes, it would be a particularly serious hit for residents of higher-tax states, many of which tend to be Democratic. So congressional Democrats are expected to fight to keep the deduction.

That said, Democratic lawmakers may be ambivalent about the deduction "since the vast majority of the benefit goes to higher income people," said Dean Baker, co-director of the liberal Center for Economic Policy and Research.

The estate tax and the alternative minimum tax

Trump wants to eliminate both of these taxes. But the estate tax and its extreme tilt toward the wealthiest Americans could make its elimination controversial, especially if taxes on the middle class are raised in order to close the revenue gap. Indeed, rather than gutting the estate tax, some Democrats would like to squeeze even more revenue from it.

As for the alternative minimum tax -- which guarantees that taxpayers with a lot of deductions pay at least a minimum amount to the IRS -- "nobody likes it, but it's expensive to repeal," Williams said.

Our Sources

Donald Trump, tweet, Sept. 13, 2017

CNBC, "Read the White House memo on President Trump's proposed tax plan," April 26, 2017

Urban Institute-Brookings Institution Tax Policy Center, "A Tax Plan Consistent With Trump’s April Outline Could Cut Revenue By Up To $7.8 Trillion," July 12, 2017

Urban Institute-Brookings Institution Tax Policy Center, "Would Workers Benefit From A Corporate Tax Cut? Not Much," Sept. 8, 2017

Urban Institute-Brookings Institution Tax Policy Center, "The State and Local Tax Deduction Doesn’t Benefit Only Blue State Households," Sept. 11, 2017

Dan Mitchell, "Because of Unresolved Issues such as Carried Interest and Revenue Neutrality, Will GOP Tax Reform Effort Become a Cluster-You-Know-What like Obamacare Repeal?" Aug. 29, 2017

New York Times, "Ryan Says Trump Cut Deal With Democrats to Avoid Partisan Fight Over Hurricane Aid," Sept. 7, 2017

Politico, "GOP lawmakers jittery over lack of tax reform details," Sept. 12, 2017

PolitiFact Wisconsin, "Pledging cuts, Donald Trump says at Wisconsin rally that U.S. has highest corporate tax rate," Dec. 15, 2016

Email interview with Dean Baker, co-director of the liberal Center for Economic Policy and Research, Sept. 8, 2017

Email interview with Dan Mitchell, conservative economist, Sept. 8, 2017

Email interview with Roberton Williams, a fellow at the Urban Institute-Brookings Institution Tax Policy Center, Sept. 8, 2017

Interview with Scott Greenberg, a senior analyst at the Tax Foundation, Sept. 12, 2017