Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

In this Feb. 27 2018 photo, White House Communications Director Hope Hicks, one of President Trump's closest aides and advisers, arrives to meet behind closed doors with the House Intelligence Committee, at the Capitol. (AP Photo/J. Scott App

According to news reports, White House communications director Hope Hicks testified to the House Intelligence Committee that she had told "white lies" as part of her job representing President Donald Trump. Within 24 hours, Hicks announced her departure from the White House.

For all of the public cynicism about politicians telling the truth, it is rare to hear a senior government spokesperson acknowledge lying, even the "white lie" variety. (The White House told some news outlets that her decision to leave was in the works well before her House Intelligence Committee testimony.)

We decided to take a closer look at how unusual it is for such officials to acknowledge not telling the press the truth. In interviews conducted largely before Hicks announced her departure, numerous public relations experts told PolitiFact that it would be hard for a spokesperson to continue to do their job effectively or remain in it at all.

"The first rule of public relations is, 'Don't lie,'" said Tracy Arrington, director of media for Blackboard Co. of Austin, Texas, and a lecturer at the University of Texas’ Stan Richards School of Advertising & Public Relations. "It isn't acceptable. And you will eventually get caught."

This is especially true for someone in as elevated a role as the White House communications director, said Colleen Connolly-Ahern, senior research fellow at Penn State University’s Arthur W. Page Center for Integrity in Public Communication. (Hicks didn't give televised briefings from the White House press room, but she did work with reporters off-camera.)

Sign up for PolitiFact texts

In fact, telling even "white lies" might have crossed a boundary with the Public Relations Society of America, the leading national association for public relations professionals. "Honesty" is one of the key elements of the society’s ethics code.

Experts drew a distinction between "spinning" and lying. The former emphasizes the positive aspects of a situation but doesn’t spread falsehoods. They also noted that there is a difference between inadvertently giving information that turns out to be incorrect and saying something that they know to be false.

"The public has come to believe that all public officials, especially press secretaries, spin, and that spin is tantamount to a lie. But that's wrong," wrote Dee Dee Myers, a spokeswoman for President Bill Clinton, in the book All the Presidents' Spokesmen by journalist Woody Klein. "Spin may be marshaling the facts in the service of an argument, the way a skilled debater would. But a lie is still a lie. And once a press secretary gets caught -- or even accused -- of being less than truthful, the game is over."

Sometimes, though, the lines aren’t entirely clear.

"Occasional deceptiveness comes with the territory, as it does with generally admirable politicians like President Barack Obama," said Rick Edmonds, a media business analyst at the Poynter Institute, the nonprofit school that trains journalists and is also the parent of PolitiFact. "This is especially true in the business and financial sphere, where certain impending events -- such as an imminent bank failure -- must be denied until the hammer drops."

Living White House press secretaries in 2001: Jake Siewert, Jerald terHorst, Ron Ziegler, Ron Nessen, Ari Fleischer, Mike McCurry, Larry Speakes, Marlin Fitzwater, and Joe Lockhart. (AP/Doug Mills)

The most common examples of dishonesty by White House spokespersons tend to involve thorny national-security issues.

For instance, during the Cuban missile crisis in 1962, Defense Department spokesman Arthur Sylvester defended President John F. Kennedy’s incomplete, even misleading, statements about what the government knew about Russian missiles in Cuba. Sylvester said that "the government has a right to lie," later doubling down on that view in congressional hearing.

"Obviously, no government information program can be based on lies; it must always be based on truthful facts. But when any nation is faced with nuclear disaster, you do not tell all the facts to the enemy," he said. (According to Klein’s book about White House press secretaries, Kennedy White House spokesman Pierre Salinger was specifically kept out of the loop for several crucial days so that he would not be forced to lie about the situation.)

Later, Jody Powell, President Jimmy Carter’s press secretary, took heat for a misleading statement about whether the United States was planning a rescue mission for U.S. hostages in Iran. And Larry Speakes, a spokesman for President Ronald Reagan, denied that an invasion of Grenada was under way when it actually was about to happen.

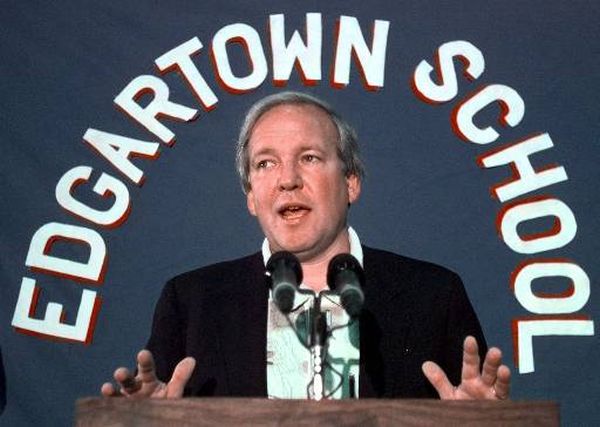

Mike McCurry briefs reporters in Edgartown, Mass., on Aug. 22, 1998, during President Bill Clinton's vacation in Martha's Vineyard. Clinton had recently ordered missile strikes on Afghanistan and Sudan. (AP/Greg Gibson)

Mike McCurry, who served as press secretary for Clinton, told PolitiFact that the key to answering delicate questions such as these without lying is "telling the truth slowly." He recalled an incident in 1998 when the Clintons were on a summer trip to Martha’s Vineyard. Reporters were asking for a "lid," which is an end to the public announcements of the day.

"However, I knew that we were about to launch a cruise missile strike against Osama Bin Laden and all hell would break out in a few hours," McCurry said. "Pressed for a ‘lid,’ I said I had a few things to check on and we would be back shortly."

One reporter came up after McCurry’s briefing and asked him if something was up. "I told him, you know there is always something going on around this president, so just let me check a few things," recalled McCurry, who is now director of the Center for Public Theology at the Wesley Theological Seminary. "These questions about national security are the most sensitive and create the dilemma. You tap dance, but never lie."

We’ve previously criticized the Obama White House’s communications shop, including press secretary Jay Carney, for sticking with Obama’s claim that if you liked your health care plan, you could keep it under the Affordable Care Act. That statement, repeated at least 37 times without sufficient qualifiers, earned our Lie of the Year for 2013. Columnist Clarence Page of the Chicago Tribune wrote that the public "was entitled to hear the unvarnished truth, not spin, from their president about what they were about to face."

Still, experts said the Trump White House and its communications strategy are different than any other they’ve seen in the past.

"This is an unprecedented situation, which unfortunately produces ‘teachable moments’ in what not to do from all sectors of government daily," said Penn State’s Connolly-Ahern.

Is it possible to regain trust once you’ve acknowledged lying? The private sector record is not promising.

"See what happened to the CEO of Volkswagen after they lied about engineering emissions cheats," said Suzanne E. Boys, public relations program director at University of Cincinnati. "See what happened to the leaders of Wells Fargo when they lied about a lot. Although reputation repair is possible for an organization, that is often achieved by offering up a scapegoat. Organizations will likely try to redeem their corporate reputation at the cost of the spokesperson or leader's individual reputation."

Carter’s spokesman, Powell, "survived because he was just such a good guy and he went drinking with the reporters every night -- it was a different Washington," McCurry said. "But he told me once that he paid a price. Everyone who’s a press secretary pays a price for it. Maybe not fair, but necessary if we are to keep the trust and confidence of the American people -- something we see now that can be easily eroded."

Speakes came clean about a few instances of making up quotes supposedly by Reagan -- but only in his memoirs after he left office. And even then, the revelations sparked negative reactions.

Speakes acknowledged making up quotes by Reagan on two occasions, including one when the president held his historic first meeting with Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev in Geneva in 1985.

Then-NBC White House correspondent Chris Wallace, who had reported the manufactured quote, told the Los Angeles Times that he was "astonished, flabbergasted" to learn that Speakes had made up the quotes. "These are two crucial events in the history of Reagan's presidency," he told the newspaper. "I don't think it should be naive of us to assume that, when the press secretary quotes the president, the president said the words."

CLARIFICATION, Mar. 5, 2018: This version of the article has modified the description of the Poynter Institute.

Our Sources

Public Relations Society of America, "PRSA Code of Ethics," accessed March 1, 2018

New York Times, "Hope Hicks to Leave Post as White House communications director," Feb. 28, 2018

CNN, "What Hope Hicks meant about white lies," Feb. 28, 2018

Washington Post, "Obituary: Arthur Sylvester, 78," Dec. 30, 1979

Los Angeles Times, "Speakes Relates How He Made Up Reagan Quotes," April 12, 1988

Woody Klein, All the Presidents' Spokesmen, 2008

PolitiFact, "Lie of the Year: 'If you like your health care plan, you can keep it,' " Dec. 12, 2013

Email interview with Michael Schudson, Columbia Journalism School professor and author of The Rise of the Right to Know: Politics and the Culture of Transparency, 1945–1975, Feb. 28, 2018

Email interview with David Greenberg, Rutgers University historian and author of the book Republic of Spin, Feb. 28, 2018

Email interview with Rick Edmonds, media business analyst at the Poynter Institute, Feb. 28, 2018

Email interview with Anthony D’Angelo, national chair of the Public Relations Society of America, Feb. 28, 2018

Email interview with Tracy Arrington, director of media for Blackboard Co. of Austin, Texas, and lecturer at the University of Texas’ Stan Richards School of Advertising & Public Relations, Feb. 28, 2018

Email interview with Marina Vujnovic, program director for corporate and public communication at Monmouth University, Feb. 28, 2018

Email interview with Colleen Connolly-Ahern, senior research fellow at Penn State University’s Arthur W. Page Center for Integrity in Public Communication, Feb. 28, 2018

Email interview with Suzanne E. Boys, public relations program director at University of Cincinnati, Feb. 28, 2018

Email interview with Mike McCurry, former press secretary for Bill Clinton, Feb. 28, 2018