Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

Mahershala Ali, left, and Viggo Mortensen, right, as Dr. Donald Shirley and Tony Vallelonga in the Oscar-nominated Green Book. (Courtesy of Universal Pictures)

Editor's note: Have you ever wondered if the movie you just saw — that claimed to be based on a real story or historical events — was really accurate? So have we. With this year’s Oscars featuring historically based movies up for Best Picture honors, we wanted to help you sort out the facts from the dramatic liberties. (We've also fact-checked BlacKkKlansman and will also fact-check Vice.) Warning, major spoilers and plot points ahead!

The movie snatching hearts and Oscar nominations feels especially good when audiences learn it’s based on a true story. But how accurate is Green Book?

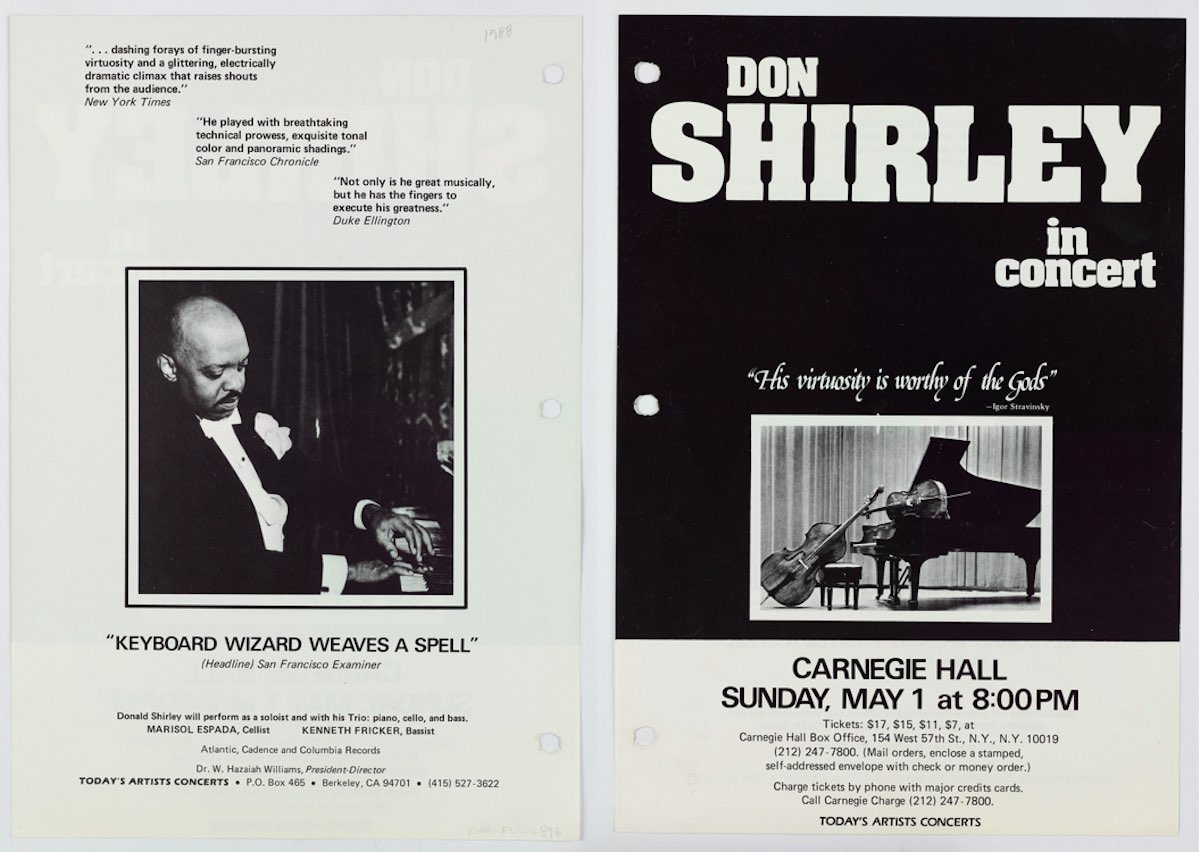

Viggo Mortensen plays Tony "Lip" Vallelonga, a brash Italian-American bouncer from the Bronx, who changes his racist views as he drives piano virtuoso Dr. Donald Shirley through a tour of the Jim Crow South. Shirley, played by Mahershala Ali, lived in a sumptuous apartment above Carnegie Hall and fought against a racist music industry that continually tried to pigeonhole his craft into the popular jazz genre.

The movie faces criticism of being a white savior film. It was co-written by Nick Vallelonga, Tony’s son, with no input from Shirley’s surviving family members about the 1962 drive.

"A symphony of lies," is how Shirley’s brother, Maurice, describes the film. But the writers stand by it. The film was nominated for five Oscars, including Best Actor and Best Picture.

Sign up for PolitiFact texts

The lack of input from Shirley’s family made for some errors. Locations and dates were altered, because the road trip at the heart of the movie took more than a year, not two months. And experts raised a few concerns about historical accuracy. But we found the basic ideas are on point.

Both men died in 2013, which makes it hard to pinpoint how closely their experiences of the trip align. Most of the movie’s scenes are adapted from Tony’s anecdotes, which Nick recorded. Other scenes are adapted from stories Shirley told Nick and his close friends.

"Family members will certainly offer you a starkly different characterization than those who knew (Shirley) as a recluse in his later years, in the Carnegie Studios, as I did," said Josef Astor, who made the documentary "Lost Bohemia" about Shirley and the other artists who lived above the music hall. "The Dr. Shirley we see in Green Book contrasts greatly to the one I knew as neighbor in the Carnegie Studios in the 1990s, but that doesn't necessarily mean one or the other is inaccurate."

Here’s what’s accurate about the movie, and what’s not.

Flyer for a Don Shirley concert in Carnegie Hall. (Courtesy of Carnegie Hall Archives)

Recordings of Shirley confirm he considered Tony more than just a driver.

"I trusted him implicitly," Shirley told Astor in an outtake from "Lost Bohemia." "You see, Tony got to be, not only was he my driver… we never had an employer-employee relationship, you don't have time for that foolishness. My life is in this man's hands, do you understand me? So we got to be friendly with one another. I taught him English."

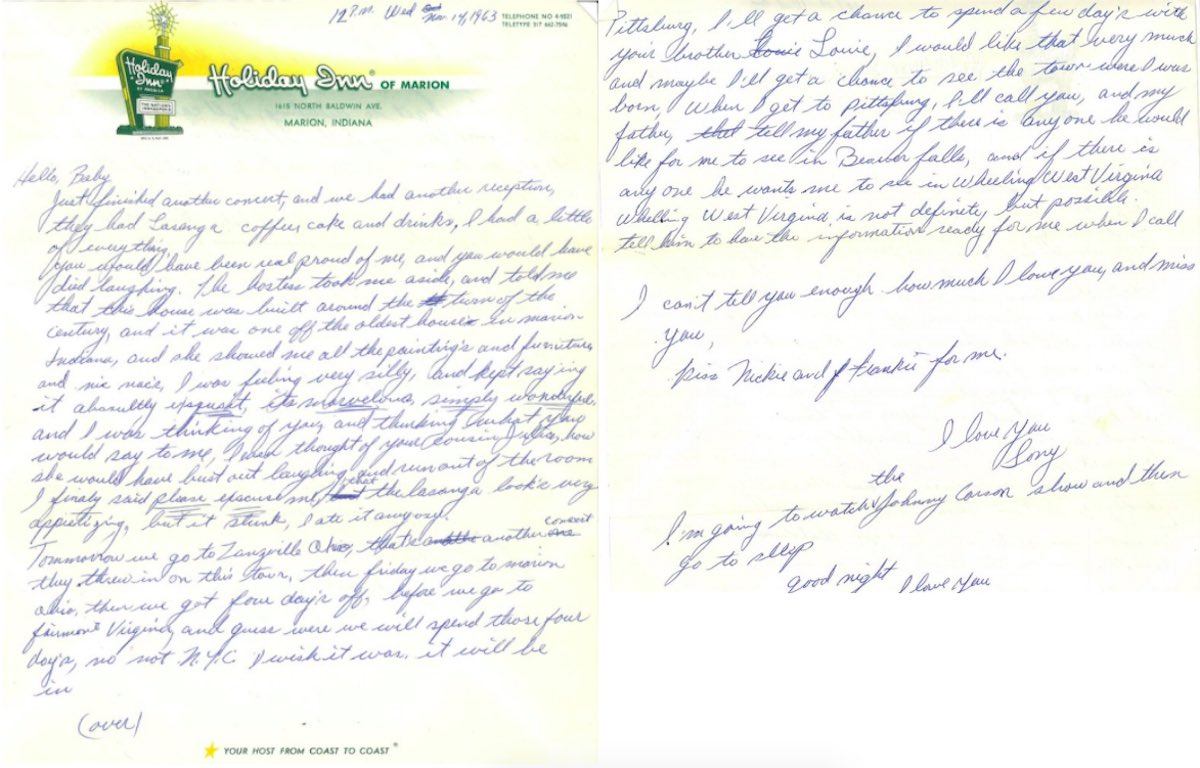

Shirley takes on teaching Tony proper diction in the movie. At first, an annoyed Tony resists, but by the end, he recites tongue twisters on the road. Shirley also teaches Tony how to infuse his prose with moving color.

"What on God’s green earth are you doing?" Shirley asks Tony as he writes home.

"A letter," Tony says.

"Looks more like a piecemeal ransom note," Shirley responds.

He goes on to dictate the rest of his letters, until Tony gets the hang of it by the end of the movie. That letter, like the others in the movie, was adapted from mementos the Vallelonga family had tucked away.

One of the letters Tony wrote his wife, Dolores, from the road while on tour with Shirley. (Courtesy of Vallelonga family)

Shirley’s impulse to impart knowledge is true to character, Astor recalls. And no doubt they grew comfortable with each other, said Michael Kappeyne, a friend and student of Shirley’s.

His family had a different take on the relationship.

"You asked what kind of relationship he had with Tony? He fired Tony! Which is consistent with the many firings he did with all of his chauffeurs over time," Shirley’s brother, Maurice, told Shadow and Act.

That’s not shocking — the reasons were illustrated in the film.

"Tony would not open the door, he would not take any bags, he would take his (chauffeur’s) cap off when Donald got out of the car, and several times Donald would find him with the cap off, and confronted him," Maurice said.

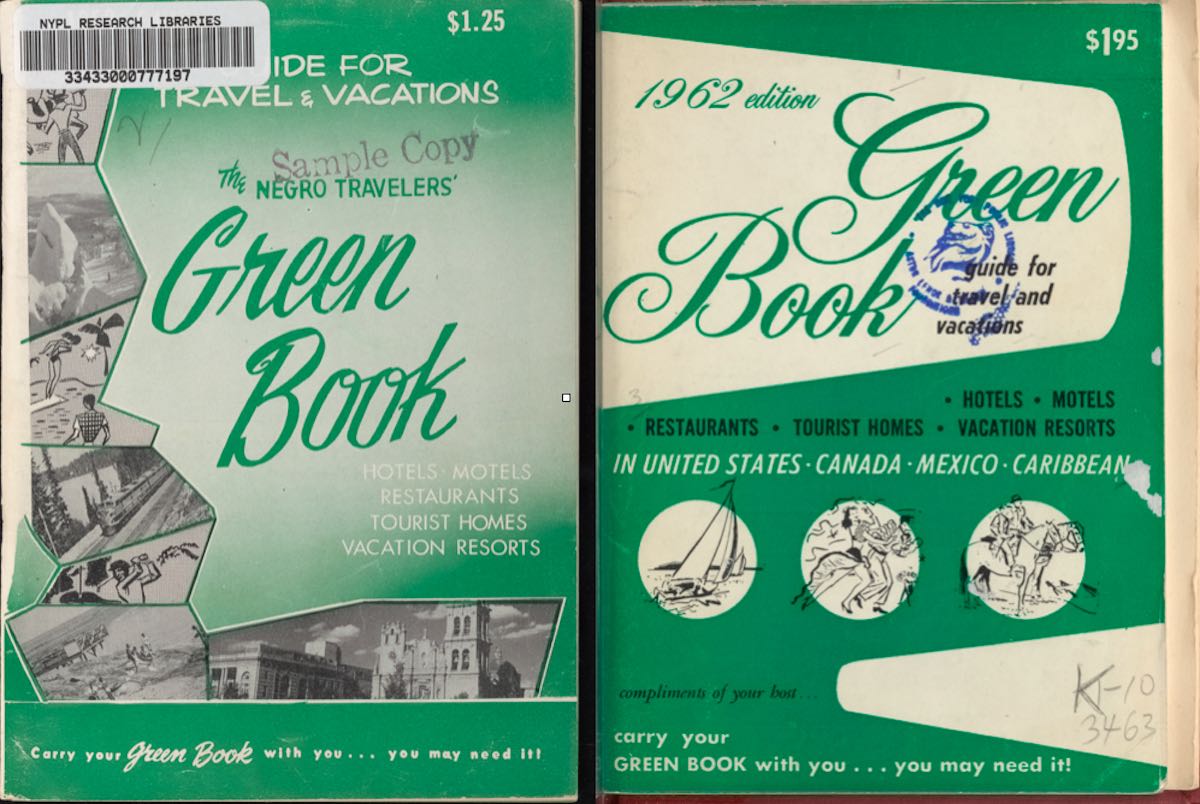

Green Book may be the title of the film, but the real Green Book gets little screen time. A record executive hands Tony a copy as he departs New York.

"You’re going to need it," he says. "It’s the book I told you about. Sometimes you’re staying in the same hotels, and sometimes you’re not."

The Negro Motorist Green Book was the most popular travel book aimed at black travelers, in publication from 1936 to 1967. Victor Hugo Green, its creator, was an African American mail carrier who lived in Harlem. His first Green Book mostly covered the New York metropolitan area, but grew to cover all 50 states, as well as Mexico and Bermuda.

The Green Book also seems to lead the protagonists astray. The two motels Shirley stays are portrayed as rundown slums, far from what the famous, fastidious musician would have picked. But the Green Book offerings were far more generous and high-end than the movie’s guide offers.

"There was everything you would ever want or need would be in the Green Book," said Candacy Taylor, author of the upcoming Overground Railroad, about the Green Book. "It wasn’t just typical travel guide with lodging and food. Beauty shops, sanatoriums, drug stores, haberdashers, liquor stores, night clubs, gas stations and the like."

Taylor said most black people knew about the Green Book, and the guide reached a circulation of about 2 million people by 1962. But Shirley never flips through the Green Book in the movie, only Tony does when looking for a place to rest.

Kappeyne said that as the artist, Shirley did not deal with particulars of his travel — it would have been up to the record company and Tony.

1959 and 1962 copies of The Negro Travelers’ Green Book. Courtesy of Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture)

Shirley was born to well-off Jamaican parents in Pensacola, Fla., and grew up in "close-knit family surroundings," Kappeyne said. His father was an Episcopal pastor with his own church. His mother, a teacher, took on a central role in Shirley’s development as a musician but died when he was 9.

The movie shows Shirley had only one estranged brother, but he had three brothers.

"I have a brother somewhere," Shirley says in one Green Book scene. "We used to get together once in a while… but it got more and more difficult to keep in touch. That’s the curse of being a musician — you’re always on the road, like a carnival worker, or a criminal."

"At that point, he had three living brothers with whom he was always in contact," Maurice told Shadow and Act. "There wasn’t a month where I didn’t have a phone call conversation with Donald."

But he was once married, and then divorced, because he "didn’t have the constitution to do a husband act as well as a concert pianist act," Shirley told Astor in his upcoming documentary, "Let It Shine."

Green Book co-writer Peter Farrelly told Newsweek he was under the impression there were not many surviving family members and admitted the writing team "screwed up."

"We’re not from around here," Tony tells a police officer after he is stopped on the side of a Mississippi road in one scene.

"No, you ain’t. So I’m gonna ask you again... what the hell you doin’ out here? And why you driving him?" the policeman asks after seeing Shirley in the back seat. "He can’t be out here at night. This is a sundown town."

Thousands of sundown towns plagued the United States, beginning in 1890, and a few persist even today, according to James W. Loewen, author of Sundown Towns. Sometimes with a sign but sometimes without, the towns had legal or unspoken constitutions to harass, drive out or even murder black residents and visitors. Other minority groups were sometimes targeted, too.

But Loewen said these were mostly a northern and western phenomena. He found only three sundown towns in Mississippi, while he encountered 506 in Illinois and over 400 in Indiana.

"I think it’s a good movie, but its sociology about sundown towns is terrible," Loewen said. "Sundown towns were incredibly rare in the South. This is in keeping, this treatment, with Hollywood’s treatment of severe racism. If we have severe racism then it must be in the Deep South. White southerners thought sundown towns were stupid — who would be the maid?"

Tony and the Mississippi policeman argue about the fact that Tony is driving a black man. The policeman calls Tony a racial slur, and Tony punches him. The camera pans to the two men in a jail cell. They are able to get out because Shirley calls in a favor to Robert Kennedy, then U.S. attorney general.

In Shirley’s own telling, Tony didn't throw blows, Shirley was not arrested, and they were driving through West Virginia.

"What happened was they stopped us and charged us for speeding in a 35 mile (per hour) zone we were going 25, okay, but they said we were going 75, and it was all pure racism," Shirley said in an interview with Astor. "They got pissed because he was white, driving me. That’s what it was about. They made us turn around and come back 50 miles to McMechen, West Virginia, okay?"

Shirley talks about his life at his piano in his Carnegie Hall studio in Astor's upcoming documentary, Let It Shine. (Courtesy of Josef Astor)

Shirley was not even allowed into the jail, except to bail Tony out. He said he didn’t have any cash on him, and the officers refused to accept his AAA card because it was out-of-state. So he asked to call a friend to wire him some money. Instead, he called Kennedy and left a message with his assistant to call him back.

"She contacted Robert Kennedy in Florida. … Now, Robert Kennedy called the number. The damn red faced ugly son of a b--- of a chief of police answered the phone. He even, as dumb as he is, recognized Robert Kennedy’s voice, as you recall, it was Robert’s voice distinctively, with his Boston accent. When he told them who he was, they couldn’t refuse him."

The officer finally accepted Shirley’s AAA card and let the men go. In the movie, the phone call was enough to let them off the hook.

The final show is set in Birmingham, Ala., right before Tony and Shirley rush home for Christmas Eve. Before the performance, Tony and the other two members of Shirley’s trio sit down for dinner at the hotel’s restaurant. When Shirley tries to join them, the host blocks his entry, citing restaurant policy. After a stand-off, Tony and Shirley decide to walk off on the tour finale.

In reality, the duo did walk off another show in Virginia or Kentucky for the same reason, as an audio recording of Tony shows.

"We didn’t do the concert but the people that were doing the concert, they pleaded with us. I said, I don’t understand. How can you beg us to do the concert when you can’t feed him?" Tony says. "I said, we’re not doing it. I called (Shirley’s) lawyer, I explained to him, he says, get out."

In the movie, they then make their way to The Orange Bird, a blues restaurant-bar down the street with a majority black crowd. As they walk out, they are almost mugged by a group of thugs crouching behind the car, but Tony shoots his gun in the air, and they scatter.

Playing Shirley, Ali gives a final performance at the Orange Bird in Green Book. (Courtesy of Universal Pictures)

In an interview with Astor, Shirley recalls he was not allowed to enter another hotel bar after a concert. The sheriff, who had watched Shirley’s concert, convinced the owner to let him in. She served him one drink, then made the last call.

As Shirley made his way to the car, he walked past a group of "about five or six thugs with rifles on their shoulders! And I walked on right past them, got into my car, drove off. And they never knew I was the one they were coming to look for. We drove all night long and ended up in Pittsburgh the next day."

Our Sources

The Green Book, Movie, November 2018

Universal Pictures Awards, Green Book Screenplay, 2018

Interview with Josef Astor, documentarian and friend of Shirley, Jan. 29, 2019

Interview with Michael Kappeyne, student and friend of Shirley, Jan. 29, 2019

Lost Bohemia, Josef Astor, 2011

Youtube, Let it Shine trailer, Nov. 19, 2018

Interview with James Loewen, author of Sundown Towns, Jan. 28, 2019

Interview with Candacy Taylor, author of the upcoming book on Green Books, Overground Railroad, Jan. 28, 2019

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The Green Book

Interview with Preston Lauterbach, author of The Chitlin’ Circuit, Jan. 29, 2019

Interview with Rob Hudson, archives manager at Carnegie Hall, Jan. 29, 2019

Time, How Green Book's Screenwriter Was Inspired to Write the Movie, Jan. 11, 2019

Vox, Green Book builds a feel-good comedy atop an artifact of shameful segregation. Yikes., Nov. 16, 2018

Shadow and Act, How 'Green Book' And The Hollywood Machine Swallowed Donald Shirley Whole, Dec. 14, 2018

Screen Rant, Nick Vallelonga Interview: Green Book, Nov. 20, 2018

Newsweek, Green Book Director Peter Farrelly Says He Was "Very Aware of the White Savior Trope" Nov. 21, 2018

The Wrap, Inside ‘Green Book': Read Tony Lip’s Real Letters From the Road Tour With Donald Shirley, Dec. 14, 2018