Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

Students walk on the campus of Miami Dade College, in Miami, on Oct. 23, 2018. (AP/Sladky)

As students across the country begin their college lives, many are also saying hello to something that could follow them long after graduation: student loans.

Student loan debt is the highest it’s ever been. And the average cost of college tuition has more than doubled in the last 30 years.

Just 58% of Americans say a four-year degree is worth the price, according to a recent survey from American Public Media’s research lab. That’s up from past years, but still a slim majority.

Mounting costs have prompted Democrats such as Sens. Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders to introduce plans to forgive outstanding student loan debts, which now total $1.48 trillion.

President Donald Trump is talking about it, too. He signed an executive order Aug. 21 to wipe away federal student loan debts owed by about 25,000 permanently disabled veterans.

Sign up for PolitiFact texts

With student debt and tuition costs, is college really worth it? PolitiFact crunched the numbers for bachelor’s and associate’s degrees and interviewed education experts.

Put simply, postsecondary education is still a reliable investment for most students.

How expensive is college?

The sticker price for tuition, room, board and other fees has skyrocketed since the 1980s.

According to the National Center for Education Statistics, the average total cost for students living on-campus at four-year public, in-state universities, was $24,320 in 2017-18. For private, for-profit universities, that cost was $32,244. For private, nonprofit institutions, it was $50,338.

Two-year associate’s degrees tend to be about half the four-year price.

For many students, these costs cannot be met without grants, financial aid, scholarships, work-studies or loans that are generally paid back with fixed monthly payments lasting years.

Although borrowing via loans is down from recent years, it’s still high. According to the NCES, about 63% of 2007-08 bachelor’s degree recipients still had student loan debt four years after graduating, and those who did not go on to get more education owed an average of $24,000.

Soon-to-be college graduates think they’ll erase their student loans in six years — but the data shows it will likely take closer to 20, according to a study by Cengage, an education company.

Only 38% of borrowers who started postsecondary education in 1995-96 had fully paid off their loans 20 years later, while 25% had defaulted on at least one loan, per the NCES.

Does college help you land a job?

College is still worth the time it takes to pay it off for most students, experts told us.

Job-seekers with at least a bachelor’s degree have a slight edge in the job hunt, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics data. In July, the unemployment rate for people 25 and older with at least a bachelor’s degree was 2.2%. For people that age with high school degrees, it was 3.6%.

Nicole Smith, chief economist at the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce, said this gap is generally wider and that college graduates tend to land jobs with less turnover.

At the same time, 41% of recent bachelor’s degree recipients and 34% of bachelor’s degree holders overall were underemployed as of June, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. That means they were working jobs that typically do not require a bachelor’s degree.

"Whether it’s a boom or a slump, you’re going to find that some people who are mismatched," Smith said, noting that other workers are similarly overemployed.

But there’s evidence that underemployed workers typically make more than co-workers who are less qualified for the same job, she said.

Do college graduates earn more?

According to the New York Fed, the average college graduate’s salary is more than $30,000 higher than the average salary for a worker with a high school diploma.

The NCES and the Bureau of Labor Statistics have recorded similar differences. Generally, higher education leads to higher wages, meaning the more you learn, the more you earn.

Over the course of a career, that can add up. The Georgetown University Center for Education and the Workforce estimated in 2011 that, over a lifetime, a bachelor’s degree is worth an average of $2.8 million. Bachelor’s degree holders bring in 31% more in median lifetime earnings than associate’s degree recipients, and they bring in 74% more than workers who stopped their education after high school.

These earnings aren’t guaranteed, however.

In order to reap the full benefits, students have to actually finish the degrees they set out to earn. But according to the NCES, only 60% of students in bachelor’s degree programs graduate in six years. That means about 40% of college students never complete their studies, and others take longer than four years to do so.

"If you’re not ready for college, it’s most likely that you’re not going to be able to make the grade," said David Bloomfield, professor of education at Brooklyn College and the City University of New York Graduate Center.

Even some students who do graduate have trouble out-earning their non-college counterparts. A 2014 study by the New York Fed found that the annual wages for the bottom 25th percentile of college graduates are no higher than the median wages for high school graduates.

Still, there’s evidence to suggest that even the worst-off college graduates do better because of their degree than they otherwise would, said Sandy Baum, senior fellow at the Urban Institute, a think tank in Washington.

"They would have also been at the bottom of the heap of high school graduates," she said of the worst-off college graduates. "So even if they earn less than the median for college graduates, still they’re better off than they personally would’ve been."

But higher salaries earned by college graduates can’t always be chalked up to the degree itself.

"We really do not know how much of the higher pay college grads earn is due to the fact that they are already more able, they have families with more resources, and they have other advantages that help them in the job market as compared to those who do not go to college," said Peter Cappelli, professor of education at the University of Pennsylvania.

What you study matters

A student’s major can actually have a bigger impact on lifetime earnings than simply going to college, the Georgetown University Center for Education and the Workforce found.

Most of the schools whose graduates go on to make big salaries focus on science, technology, engineering and math, according to a study by the compensation-data firm PayScale.

STEM majors also lead to the highest-paying jobs, according to another Georgetown University study. The difference in median annual earnings between the highest- and lowest-paying bachelor’s degrees is $39,000.

Jobs such as engineering often pay mid-career workers six-digit salaries. Careers in education and social services, for example, pay much less.

When does college pay off?

But salaries aren’t everything. Some of the highest-paying jobs require the most schooling, leaving students with more debt. And some low-paying jobs do, too.

"You have to be able to earn enough to recoup the cost and time of going to college," Cappelli said. "If it takes you a long time to graduate, if you have lots of student debt, if you’re in a low-paid field, the advantage shrinks."

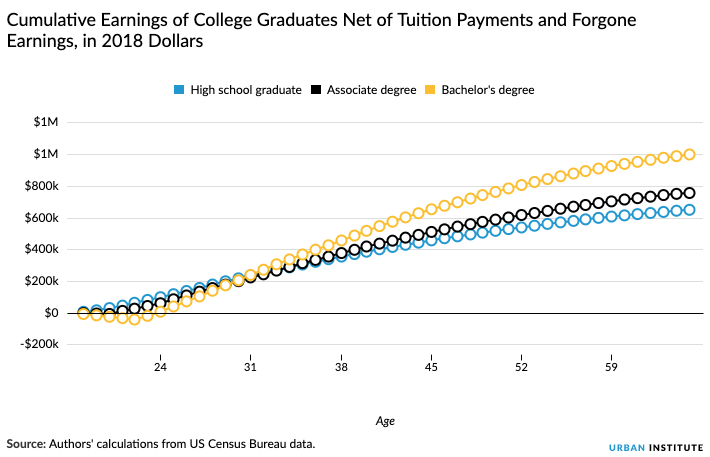

The Urban Institute tried pinpointing when bachelor’s and associate’s degree recipients reach the point at which their extra earnings compensate for the costs of paying for college and taking time out of the workforce.

"Most students who earn bachelor’s degrees will reach this break-even point about eight years after they graduate," the study said, but others "may never come out ahead."

In general, the median worker who earns an associate’s degree in three years reaches this point by age 34, and the median worker who gets a bachelor’s degree in five years does so by 31, the study estimated. But many factors can shift the pay-off age — including student loans.

"It really depends on what that student’s post-graduate career looks like," Bloomfield said. "But there’s obviously a significant degree of delayed gratification."

Our Sources

National Center for Education Statistics, "Tuition costs of colleges and universities," 2019

National Center for Education Statistics, "Average undergraduate tuition and fees and room and board rates charged for full-time students in degree-granting postsecondary institutions, by control and level of institution and state or jurisdiction: 2016-17 and 2017-18," Nov. 2018

National Center for Education Statistics, "Average total cost of attendance for first-time, full-time undergraduate students in degree-granting postsecondary institutions, by control and level of institution, living arrangement, and component of student costs: Selected years, 2010-11 through 2017-18," Nov. 2018

National Center for Education Statistics, "Price of Attending an Undergraduate Institution," April 2019

National Center for Education Statistics, "The Debt Burden of Bachelor’s Degree Recipients," April 2017

National Center for Education Statistics, "Graduation rates," 2019

National Center for Education Statistics, "Annual Earnings of Young Adults," February 2019

National Center for Education Statistics, "Repayment of Student Loans as of 2015 Among 1995–96 and 2003–04 First-Time Beginning Students," October 2017

Bureau of Labor Statistics, "The Employment Situation — July 2019," Aug. 2, 2019

Bureau of Labor Statistics, "Measuring the value of education," April 2018

Bureau of Labor Statistics, "May 2018 National Industry-Specific Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates," April 2, 2019

The College Board, "Trends in Higher Education," accessed Aug. 21, 2019

Federal Reserve Bank of New York, "Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit," August 2019

Federal Reserve Bank of New York, "The Labor Market for Recent College Graduates," Feb. 6, 2019

Federal Reserve Bank of New York, "Despite Rising Costs, College Is Still a Good Investment," June 5, 2019

Federal Reserve Bank of New York, "College May Not Pay Off for Everyone," Sept. 4, 2014

The Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce, "The College Payoff," 2011

The Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce, "Five Rules of the College and Career Game," 2018

The Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce, "The Economic Value of College Majors," 2015

The Urban Institute, "Understanding College Affordability: Breaking Even," accessed Aug. 22, 2019

The Urban Institute, "Higher Education Earnings Premium," February 2014

PayScale, "College Salary Report," 2019

PayScale, "Average Salary for Industry: Technical and Trade School," Aug. 17, 2019

The University of California-Los Angeles, "The American Freshman: National Norms Fall 2017," accessed Aug. 21, 2019

Cengage, "College Graduates Optimistic About the Future Despite Mounting Loan Debt and Housing Costs, New Analysis Finds," May 15, 2019

APM Research Lab, "APM Survey: Should public higher ed be free? And is a four-year college degree currently worth the cost?" March 11, 2019

U.S. News, "Is College Worth the Cost?" June 17, 2019

CBS News, "Graduates of these U.S. colleges earn the most," Aug 20, 2019

Forbes, "Student Loan Debt Statistics In 2019: A $1.5 Trillion Crisis," Feb. 25, 2019

NBC News, "Americans Split on Whether 4-Year College Degree Is Worth the Cost," Sept. 7, 2017

The Washington Post, "Is college worth the cost? Many recent graduates don’t think so," Sept. 30, 2015

PolitiFact, "Elizabeth Warren: Does her wealth tax pay for her child care and higher education plans?" April 25, 2019

PolitiFact, "Sanders’ latest claim about college costs only applies to public universities," June 26, 2019

Email interview with Peter Cappelli, professor of management at the Wharton School and professor of education at the University of Pennsylvania, Aug. 21, 2019

Phone interview with David Bloomfield, professor of education at Brooklyn College and the City University of New York Graduate Center, Aug. 22, 2019

Phone interview with Sandy Baum, senior fellow in the Income and Benefits Center at the Urban Institute, Aug. 22, 2019

Phone interview with Erin Dunlop Velez, education research analyst at RTI International, Aug. 22, 2019

Phone interview with Nicole Smith, research professor and chief economist at the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce, Aug. 23, 2019