Get PolitiFact in your inbox.

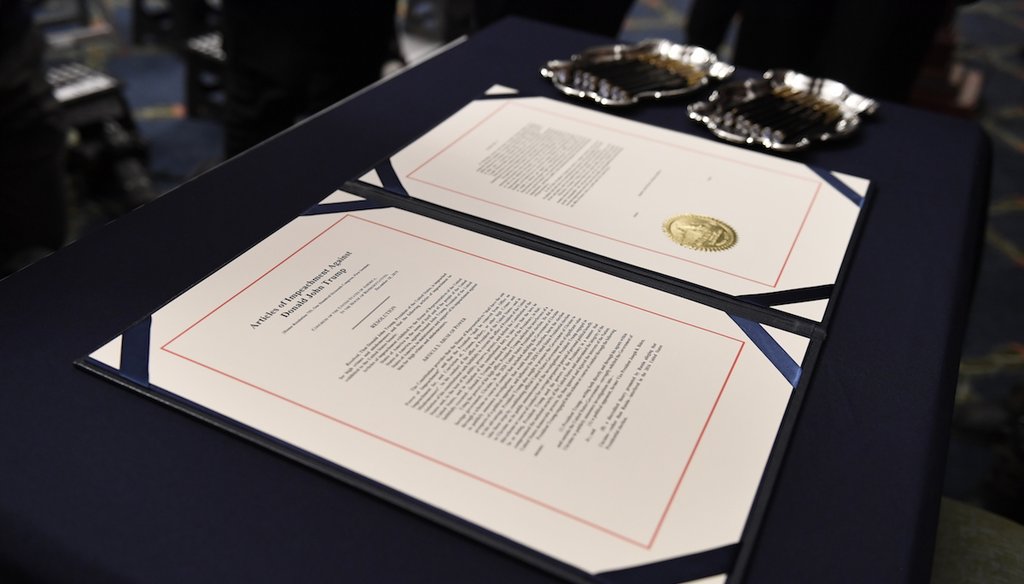

The articles of impeachment against President Donald Trump on the desk before House Speaker Nancy Pelosi of Calif. (AP images)

After a weeks-long delay, the process of impeaching and removing President Donald Trump is moving forward again.

On Jan. 15, the House voted to formally send to the Senate the impeachment articles that had passed the House in mid-December.

What happens next depends heavily on precedent from prior impeachment trials, though some wild cards could be in store.

Here’s a rundown of what to expect as the Senate trial gets under way.

What’s next?

Impeachment is a "privileged" resolution, which means that the Senate must take it up in place of other pending business.

Two-thirds of senators, 67 if all are present, are required to remove the president. That means that Democrats would need 20 Republican votes to remove Trump, an extraordinarily high bar in a polarized partisan era.

A group of House members, known as managers, serve the role of prosecutors in the Senate. There’s no fixed number of manager slots, but Pelosi has officially named seven: Democratic Reps. Adam Schiff and Zoe Lofgren of California, Jerry Nadler and Hakeem Jeffries of New York, Val Demings of Florida, Jason Crow of Colorado and Sylvia Garcia of Texas. (in 1998, House Republicans named 13 managers for the impeachment trial of Bill Clinton.)

Meanwhile, the president is free to choose his own defense team, which will represent him in the Senate proceedings. This team will play a role analogous to defense attorneys. The members of this team have not been publicly announced yet.

Overall, though, there aren’t that many similarities between a Senate trial and a criminal trial.

"Rules of evidence do not apply here, because the senators are supposed to be sufficiently sophisticated not to need the protections that evidentiary rules provide against a jury's being easily manipulated or confused," Michael Gerhardt, a University of North Carolina law professor who testified before the Judiciary Committee on behalf of impeaching Trump, told PolitiFact in December.

What rules govern the process?

The current Senate rules for impeachment have been in force since 1986, and were used to govern Clinton’s impeachment trial. This version relies heavily on rules that go back to the impeachment trial of President Andrew Johnson in 1868.

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., "seems to be following the Clinton trial model and arguing it was a good model," said Stephen Griffin, a law professor at Tulane University.

Shortly before the House officially moved to transmit the impeachment charges to the Senate, McConnell’s office released a rough schedule for the start of the trial.

As early as the afternoon of Jan. 16, McConnell’s office said, the Senate would take up the articles and request the presence of Chief Justice John Roberts to be sworn in. The chief justice, who according to the Constitution presides over the trial, would then swear in the senators.

What oath do senators swear for an impeachment trial?

Every member of the Senate must take an oath that says they will "do impartial justice according to the Constitution and laws; so help me God."

Some have questioned what this means for senators who have stated their conclusion in advance.

For instance, McConnell told Fox News’ Sean Hannity, "Everything I do during this, I'm coordinating with the White House counsel. There will be no difference between the president's position and our position as to how to handle this." Meanwhile, some senators who are also Democratic presidential candidates have said publicly that they support Trump’s impeachment.

However, experts don’t expect this paradox to make any difference.

"It’s a fun bludgeon to hit each other with, but practically speaking, it doesn’t mean anything," said Frank O. Bowman III, a professor at the University of Missouri School of Law. "There’s no provision for disqualifying senators. Who would enforce it?"

How does a Senate trial work?

The rules say that sessions are to be held six days a week, although 51 senators can vote to change that schedule.

Since all senators must be present during the trial, it’s hard to conduct any other official Senate business. That requirement also squeezes the Democratic senators who are running for president, since the Iowa caucuses and New Hampshire primary are coming up over the next few weeks.

Experts expect that both sides will be granted equal time to make their case. There will probably be a separate period for senators, or attorneys on either side, to ask questions, Griffin said.

Senators who want to question witnesses must put their query into writing. This is "likely to make it somewhat less raucous" than the House committee hearings, Bowman said.

How strong is the case for including, or excluding, witnesses?

Perhaps the biggest question mark involves whether witnesses will be called — and if so, how many, and who.

Minority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., has proposed calling such senior officials as former National Security Adviser John Bolton and acting White House Chief of Staff Mick Mulvaney to testify in the Senate after rejecting House entreaties to appear there.

But Republicans could argue for witnesses of their own who Democrats would rather not see called, such as former Vice President Joe Biden or his son Hunter. Trump’s impeachment was sparked by charges that the president had misused his authority to demand Ukrainian help on securing dirt on Biden, a potential 2020 opponent.

The Trump administration has taken a muscular view of its rights to reject congressional demands to testimony, including a letter in which White House Counsel Pat Cipollone wrote that "President Trump and his administration cannot participate in (the House’s) partisan and unconstitutional inquiry under these circumstances."

The courts may eventually decide whether Trump administration officials must testify, but for now, the Senate appears to be kicking the can down the road. The indications so far are that the trial will start while the question of witnesses remains to be decided later.

That’s how the Clinton trial proceeded. Ultimately, after the trial began, the Senate did call three witnesses — White House intern Monica Lewinsky, whose sexual relationship with Clinton took center stage in the impeachment battle, and Vernon Jordan and Sidney Blumenthal, who were allies of Clinton. They appeared via video testimony.

In the impeachment inquiry into President Richard Nixon, which ended with Nixon’s resignation before impeachment articles could be approved by the House, the disputes involved pieces of evidence rather than witness testimony, said James Robenalt, a lawyer who teaches a course on Watergate.

Most famously, these included Nixon’s Watergate tapes and other presidential papers. Eventually, the Supreme Court ruled, 8-0, that the White House had to release the tapes and papers.

Nixon’s record on in-person testimony was less hard-line. For instance, the White House sent a letter to White House Counsel John Dean that waived attorney-client privilege and executive privilege, which paved the way for Dean to present his blockbuster testimony.

"I am not aware of any court case that the Nixon administration filed to keep people from testifying before Congress," he said. Historically, Robenalt said, "the matter has almost always been handled through negotiation between the two branches without judicial involvement."

But today, heightened partisan divides make such agreements difficult, experts said.

How powerful is the chief justice in the trial?

Per constitutional mandate, Roberts presides over the trial. But he is not an all-powerful force, because a bare majority of senators can overrule him.

All it takes is 51 votes to change the rules, assuming all members are present. (Under the rules, filibusters are effectively barred.)

McConnell has a majority of 53 seats, but Democrats hope to lure support, at least on some issues, from several Republican senators, notably Mitt Romney of Utah, or moderates such as Susan Collins of Maine or Lisa Murkowski of Alaska. Schumer, meanwhile, needs to prevent defections from red-state senators in his own conference, such as Joe Manchin of West Virginia.

"The minority leader has leverage only if the majority leader’s plans leave three or more Republicans opposed or undecided," Steven Smith, a political scientist and Senate expert at Washington University in St. Louis, told us in December. "Then the minority leader has to have an attractive alternative that appeals to those Republicans and keeps his own party in line."

The presiding chief justices in the 19th century impeachment trial of Andrew Johnson and the trial of Clinton tended to be deferential to senators rather than ruling the trial with an iron fist.

"What’s really up in the air is what happens when either side starts making motions to Chief Justice Roberts," Griffin said. "Will he rule on them independently, or will he follow McConnell’s ‘advice’? That’s really what happened in the Clinton trial. So, roughly, the first part of the trial is clear to me — it will follow the Clinton model. The second part is not set and could get really wild, depending also on the release of additional evidence."

Our Sources

Senate impeachment rules, 1986 version

Senate Historical Office, impeachment page, accessed Dec. 18, 2019

Statement from the press office of Sen. Mitch McConnell, R-Ky.

PolitiFact, "What’s next after Trump’s impeachment?" Dec. 18, 2019

Vox.com, "9 questions about Trump’s impeachment trial you were too embarrassed to ask," Jan 15, 2020

Lawfare, "White House Letter to Congress on Impeachment Inquiry," Oct. 8, 2019

Steven Smith, "What to expect when you’re expecting a Senate impeachment trial," Jan. 10, 2020

CNN, "List: House impeachment managers announced for Trump Senate trial," Jan. 15, 2020

Email interview with Steven Smith, political scientist at Washington University in St. Louis, Dec. 18, 2019

Email interview with Michael Gerhardt, University of North Carolina law professor, Dec. 18, 2019

Interview with Frank O. Bowman III, professor at the University of Missouri School of Law, Dec. 18, 2019

Email interview with Stephen Griffin, law professor at Tulane University, Jan. 15, 2020

Email interview with John Dean, Nixon White House counsel, Jan. 15, 2020

Email interview with James Robenalt, attorney who teaches a course on Watergate, Jan. 15, 2019