Lower cost of prescription drugs

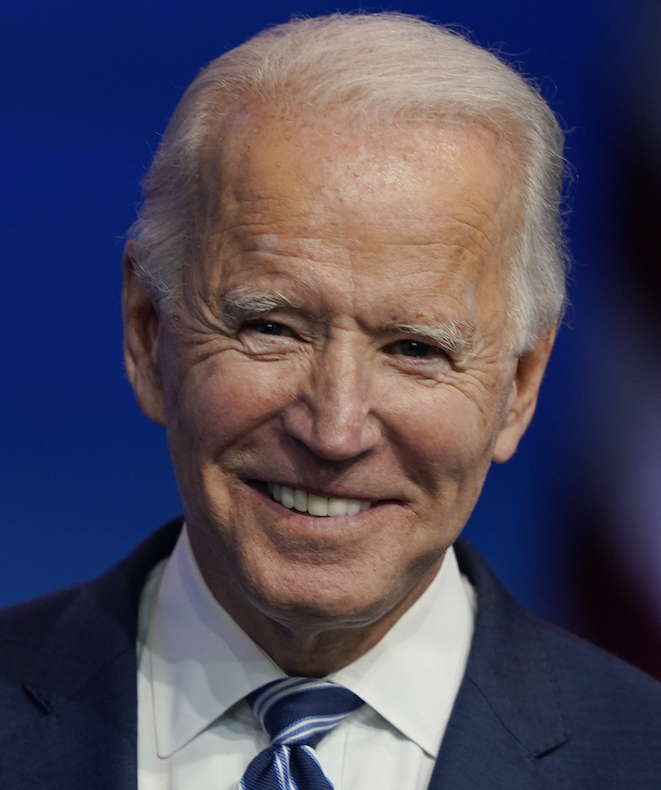

Joe Biden

"I’m going to lower prescription drugs by 60%, and that’s the truth."

Biden Promise Tracker

Compromise

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.