Protect military personnel and veterans from deportation

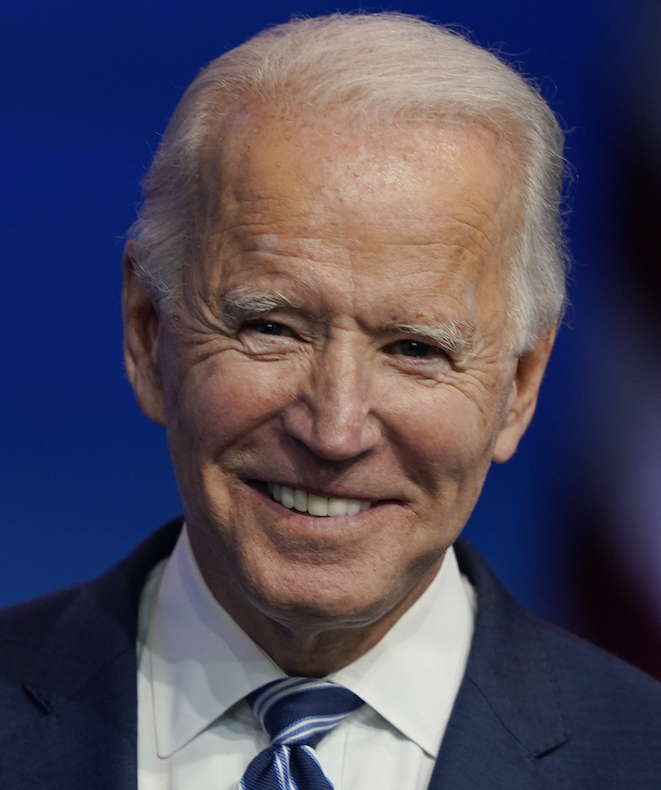

Joe Biden

"Protect undocumented members of our armed services, veterans, and their spouses from deportation, because if you are willing to risk your life for this country, you and your family have earned the chance to live safe, healthy, and productive lives in America. ... Biden will not target the men and women who served in uniform, or their families, for deportation."

Biden Promise Tracker

Compromise