Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

President Donald Trump has said he’d "love to speak" to special counsel Robert Mueller but that some of his lawyers advise against it.

The latest member of Trump’s legal team, Rudy Giuliani, said Trump is under no obligation to comply with a subpoena from Mueller and his team about the Russia investigation.

"We don't have to," Giuliani told ABC News host George Stephanopoulos on May 6. "He's the president of the United States. We can assert the same privilege as other presidents have."

Is being president enough to stymie a subpoena? There’s some historical precedent, but no exact fit legally.

"Historically, presidents from Jefferson onward have generally cooperated and, subject to time and day and venue accommodations, given over requested documents, answered interrogatories, and given testimony," said Douglas Kmiec, who headed the Office of Legal Counsel under presidents Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush and was later appointed ambassador to Malta by President Barack Obama.

Sign up for PolitiFact texts

Giuliani mentioned President Bill Clinton, so we’ll look at that case, as well as the other legal landmark, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled whether President Richard Nixon had to hand over tapes related to Watergate.

Neither is identical to Trump’s situation, and no one can say with certainty how a court would rule. For that reason, we won’t offer a rating.

That said, most legal experts suggested that being president doesn’t offer the blanket protection Giuliani suggested. There are, however, enough gaps in precedent that Trump’s team could raise legal challenges that the courts would have to take seriously.

President Bill Clinton gives videotaped grand jury testimony on Aug. 17, 1998. (AP /APTV)

Paula Jones pressed a civil suit against Clinton for making unwanted sexual advances when he was governor of Arkansas. Clinton’s lawyers fought the suit from every angle they could. The question that went to the U.S. Supreme Court was whether civil suits against a sitting president had to wait until his or her term ended. A lawsuit, Clinton’s lawyers said, "could distract a president from his public duties."

Without a single dissenting vote, the court rejected every argument from Clinton’s side. Good planning, the justices concluded, could take care of anything that might interfere with Clinton’s official work.

That pragmatic approach allowed the court to sidestep the key constitutional question of "whether a court may compel the president's attendance at any specific time or place."

So what’s the significance for Trump?

If the court green-lighted a presidential interview in a civil suit such as the Jones case, it might be even more likely to do so in a criminal investigation.

"The interests of the grand jury are generally regarded as far weightier than the interests of any private civil litigant," University of Texas law professor Steve Vladeck and Benjamin Wittes at the Brookings Institution wrote in a recent blog post. "It’s hard to see how the courts could contend that the president must answer a civil complaint from Paula Jones but then contend that he need not answer a criminal investigative subpoena."

But the opposite could also happen with a criminal case. The Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel suggested in 2000 that the criminal aspect could actually make it less, not more, likely that a president could argue against testifying. Because there’s less on the line with a civil suit, there’s more flexibility in scheduling interviews than there would be in a criminal case.

"Criminal litigation uniquely requires the president's personal time and energy, and will inevitably entail a considerable if not overwhelming degree of mental preoccupation," the office wrote.

That degree of involvement could seriously inhibit a president’s ability to handle his workload. Given this, it’s unclear whether a court would allow a criminal proceeding, especially in the absence of impeachment, to take such a toll on the presidency.

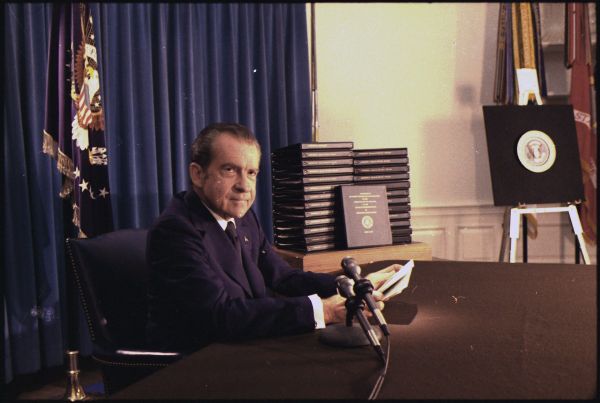

President Richard Nixon points to transcripts of the White House tapes, April 29, 1974. (AP)

To gauge what the Supreme Court has found in a criminal case involving a president, the key precedent is United States vs. Nixon.

In that Watergate-related case, special prosecutor Leon Jaworski wanted tapes of Nixon talking to his aides. Nixon, citing executive privilege, refused to hand them over.

The court unanimously sided with the prosecution.

"Neither the doctrine of separation of powers, nor the need for confidentiality of high-level communications, without more, can sustain an absolute, unqualified presidential privilege of immunity from judicial process under all circumstances," the justices wrote.

The opinion said that if the materials Jaworski sought met the test of being specific and relevant to the prosecution of the Watergate conspirators, then Nixon had to comply.

This suggests that presidents are not exempt from subpoenas in a criminal investigation — but it may depend on the nature of the subpoena.

Saikrishna Prakash, professor and Miller Center senior fellow at the University of Virginia School of Law, said the court might decide that asking for a set of materials, such as tapes, is different from demanding that the president sit down for an interview.

Trump’s lawyers are laying the groundwork to argue that a subpoena for questioning would be overly broad, he added.

"They are trying to make it look like the special counsel is engaging in a massive fishing expedition," Prakash said. "They could fight the subpoena on the grounds that it isn’t specific, and that battle could stretch out for years."

Prakash also said that preparing and then answering questions for a day or more would take more time out of the president’s work life than simply handing over tapes, which can mostly be handled by the president’s legal team.

The Trump team could argue that some potential subpoena requests fall too far outside the scope of Mueller’s investigation.

"It is fair to say that the greater the distance from the core reason for special counsel appointment, the lesser the obligation of the president to respond to a subpoena," Kmiec said.

This possibility has become more relevant in light of charges filed by Mueller against Paul Manafort, Trump’s former campaign chair.

Manafort’s legal team asked a judge to dismiss the charges. T. S. Ellis III, the district court judge for the eastern district of Virginia, questioned in open court whether the charges against Manafort, involving alleged bank fraud before his involvement in the Trump campaign, were too far removed from the special counsel’s primary responsibility of probing Russian influence on the campaign. (Ellis has not yet ruled on Manafort’s request.)

Kmiec added that the special counsel is considered an "inferior officer" not subject to Senate confirmation, "and inferior officers by definition are intended to have less prosecutorial discretion."

If Mueller’s team finds collusion between the Trump campaign and Russia, it would have happened before Trump became president. That could pose another problem for Giuliani’s argument that being president means Trump doesn’t need to comply with a subpoena.

"There’s no executive privilege that would apply to that," Prakash said.

But if Mueller pursues an obstruction of justice line of questioning, the issues become murkier. That approach would involve official acts taken while in the Oval Office, and the bar would be higher to justify a subpoena.

"If Mueller doesn’t have evidence that Trump had a corrupt motive, then as a matter of public policy, you wouldn’t want to open the door to that sort of challenge," Prakash said. "If suspicion is sufficient reason to investigate a president, then any official act could be questioned on the same basis."

But Prakash added, we don’t know what information Mueller has.

Finally, Trump faces some tactical considerations.

If Mueller succeeds in bringing Trump before a grand jury, he would need to appear without a lawyer by his side. The proceedings would be secret and under Mueller’s full control.

But if Trump agrees to an interview, then his lawyers will be present and they can negotiate the terms of the process.

Trump could choose to plead the Fifth Amendment against self-incrimination, but that could open the door to impeachment. So could a decision to simply ignore a judicially backed subpoena.

During Watergate, Nixon ultimately complied after the Supreme Court issued its unanimous ruling.

"There would have been a constitutional crisis if he had ignored" the court’s ruling, said James D. Robenalt, an attorney and creator of a continuing legal education class on Watergate.

Our Sources

ABC News, This Week with George Stephanopoulos, May 6, 2018

Office of Legal Counsel, "A Sitting President's Amenability to Indictment & Criminal Prosecution," Oct. 16, 2000

Steve Vladeck and Benjamin Wittes, "Can the Presidency Trump a Special Counsel Subpoena?" May 2, 2018

Washington Post, "Can Mueller subpoena President Trump? Why no one knows for sure," May 7, 2018

Vox.com, "Can Mueller subpoena Trump? Legal experts say yes — but it’s tricky," May 2, 2018

PolitiFact, "Obstruction of justice, presidential immunity, impeachment: What you need to know," May 17, 2017

Interview with James D. Robenalt, an attorney and creator of a continuing legal education class on Watergate, May 7, 2018

Email interview with Aaron H. Caplan, professor at Loyola Law School in Los Angeles, May 8, 2018

Email interview with Steve Vladeck, University of Texas law professor, May 7, 2018

Email interview with Douglas W. Kmiec, Pepperdine University law professor, May 7, 2018

Interview, Saikrishna Prakash, professor of law, University of Virginia School of Law, May 7, 2018

PolitiFact Rating:

PolitiFact Rating: